EU Should Raise Issue, Pledge Aid at Conference

In response to these allegations, the Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) in Turkey’s Ministry of Interior provided Human Rights Watch with a lengthy statement, which said, in part, that “while maintaining the security of borders against terrorist organizations, Turkey continues to accept Syrians in need coming to the borders, and never opens fire on or uses violence against them.”

The DGGM said that it registered 510,448 Syrians coming through the designated border gates in 2017, and 91,866 so far in 2018, and provided them with temporary protection. As seen from the numbers, the DGMM statement said, “allegations suggesting that Syrians are not registered are not true.” It does not appear that Turkish authorities conducted an investigation into Human Rights Watch’s specific findings.

In mid-February, Human Rights Watch spoke by phone with 21 Syrians about their repeated failed attempts to cross into Turkey with smugglers. Eighteen of them said that intensified Russia-Syrian airstrikes in Deir al-Zour and in Idlib had repeatedly displaced them until they finally decided they had no option but to risk their lives and flee to Turkey.

Those interviewed described 137 incidents, almost all between mid-December and early March, in which Turkish border guards intercepted them just after they had crossed the border with smugglers. Human Rights Watch spoke with another 35 Syrians stuck in Idlib who had not tried to escape for fear of being shot by border guards.

Nine people also described 10 incidents between September and early March in which Turkish border guards shot at them or others ahead of them as they tried to cross, killing 14 people, including 5 children, and injuring 18.

Civilians in Idlib have also been caught in the crossfire between Kurdish and Turkish forces during the offensive by Turkey in the Kurdish-held town of Afrin in Syria, north of Idlib, which began on January 20.

In November, the United Nations refugee agency said in its latest country guidance on Syria that “all parts of Syria are reported to have been affected, directly or indirectly, by one or multiple conflicts” and therefore maintained its long-standing call on all countries “not to forcibly return Syrians.”

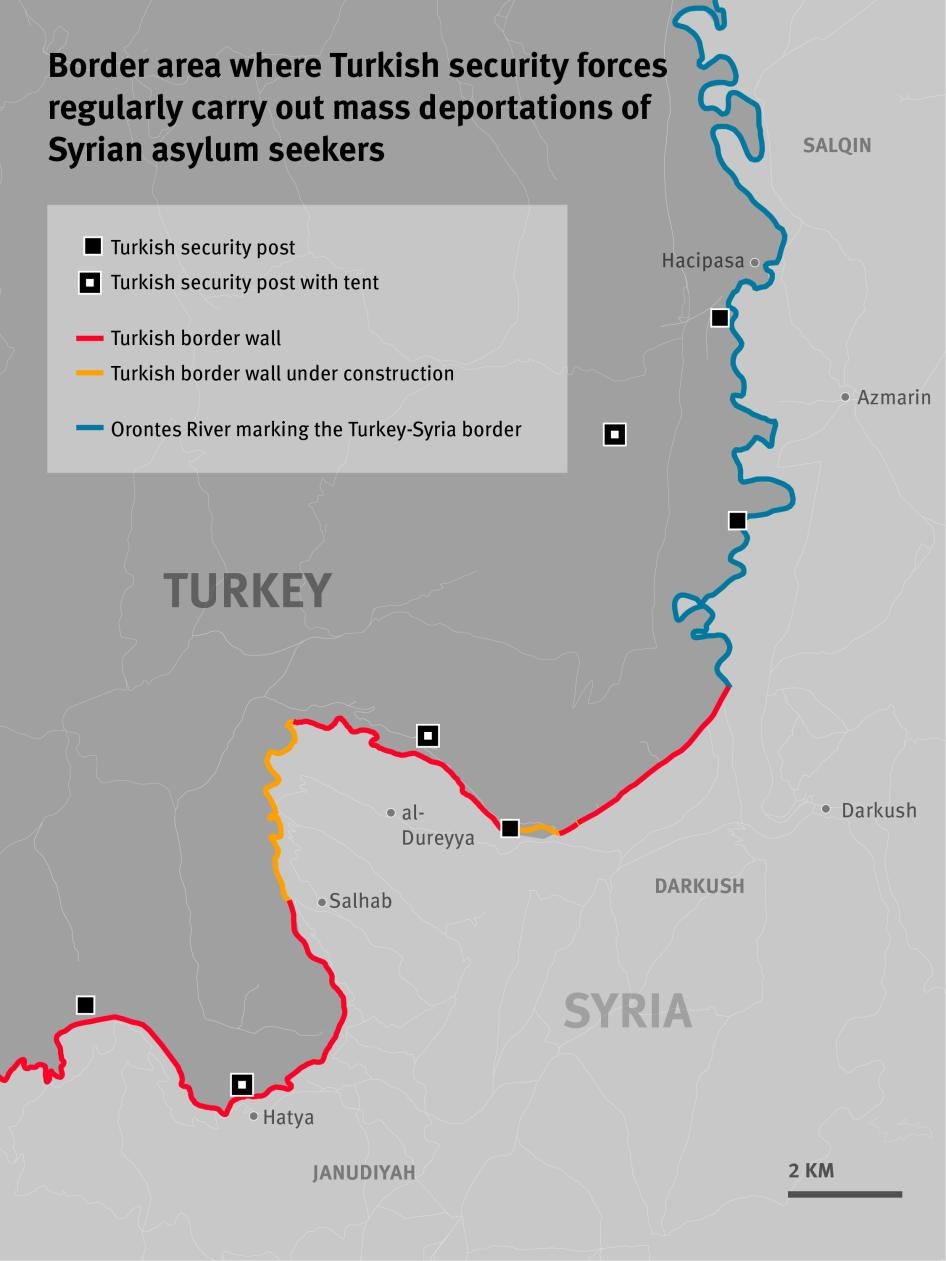

Syrians who tried to enter Turkey said they were intercepted after they crossed the Orontes River or near the internally displaced persons camp in al-Dureyya. They said Turkish border guards deported them along with hundreds, and at times thousands, of other Syrians they had intercepted. They said the guards forced them to return to Syrian territory at an informal crossing point at Hatya or across a small dam on the Orontes River known as the Friendship Bridge that aid agencies have used.

Human Rights Watch obtained satellite images of both crossing points and of four security posts with large tents set up on basketball courts in the immediate border area where asylum seekers said they were held before being sent back to Syria.

The findings follow a February 3 Human Rights Watch report on Turkey’s border killings and summary pushbacks of asylum seekers between May and December 2017 and similar findings in November 2015 and May 2016.

In response to the February 3 report, a senior Turkish official repeated his government’s long-standing response to such reports, pointing out that Turkey has taken in millions of Syrian refugees. Human Rights Watch described its latest findings in a letter on March 15 to Turkey’s interior minister, requesting comment by March 21.

Turkey is hosting over 3.5 million Syrian refugees, according to the UN refugee agency. Turkey deserves credit and support for its generosity and is entitled to secure its border with Syria.

However, Turkey is also obliged to respect the principle of nonrefoulement, which prohibits countries from returning anyone to a place where they face a real risk of persecution, torture, or inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment. This includes a prohibition on rejecting asylum seekers at borders that would expose them to such threats. Turkey is also obliged to respect international norms on the use of lethal force as well as the rights to life and bodily integrity.

Turkey insists that it respects the principle of nonrefoulement. “Syrians are accepted and taken under protection in Turkey and Syrians who have entered into Turkey somehow and demand protection are definitely not sent back and the reception and registration procedures are carried out,” the DGMM’s statement in response to this report said. “Syrians coming to Turkey are under no circumstances forced to go back to their own country; their registration is continuing and these foreigners can benefit from many rights and services in Turkey.”

As of December, Turkey had completed almost 800 kilometers of a planned 911-kilometer border barrier with Syria, which consists of a rocket-resistant concrete wall and steel fence. The satellite imagery Human Rights Watch obtained of the area where Syrians say they crossed with smugglers shows areas without a wall.

Turkey’s continued refusal since at least mid-2015 to allow Syrian asylum seekers to cross the border legally has been reinforced by a controversial EU-Turkey March 2016 migration agreement to curb refugee and migration flows to the European Union. The EU should instead be working with Turkey to keep its borders open to refugees, providing financial support for Turkey’s refugee efforts, and sharing responsibility by stepping up resettlement of refugees from Turkey, Human Rights Watch said.

“The EU should stop ignoring Turkey’s mass refugee deportations,” Simpson said. “The meeting in Bulgaria is a clear opportunity for the EU governments and institutions to change course and ramp up efforts to help Turkey protect Syrian refugees including through increased refugee resettlement.”

For more details about Turkey’s mass border pushbacks and the situation displaced Syrians face in Syria’s Idlib governorate, please see below.

Turkey’s land borders are legally protected by army border units of the Turkish Armed Forces. Gendarmerie also on duty at the borders operate under the authority of the land forces command. There are also gendarmerie stations near the borders charged with regular rural policing activities. This report refers to border guards without specifying if they are soldiers or gendarmes since many of those interviewed did not provide or do not have such specific information.

Regular Mass Pushbacks at the Turkish Border

Between February 14 and 20, Human Rights Watch interviewed the 21 Syrian asylum seekers who had tried multiple times to cross the border. Human Rights Watch interviewed them by cell phone and explained the purpose of the interviews and gave assurances of anonymity. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences.

They described 137 incidents – 107 of them between January 1 and March 6 – in which Turkish border guards intercepted them at the border near the Syrian town of Darkush and held them at nearby security posts and then deported them back to Syria with hundreds, and at times thousands, of others.

A man from Deir al-Zour governorate who fled Syrian government attacks on his village in September 2017 said border guards intercepted him nine times in January and the first half of February in border areas close to the al-Dureyya displaced people’s camp in Syria.

Describing three incidents in February, he said:

Each time they insulted the men, calling them “Syrian traitors.” They forced some of them to collect firewood. Then they took all of us in military trucks to a basketball court at a security post near the Hatya border gate. There was also a big tent there. They put us all in the tent and kept us overnight. They didn’t give us any food or water or let us go to a proper toilet. There were so many in the tent, that we were spilling out into the open of the basketball court. We were hundreds of people. The next morning, they took us all back to the border in buses.

Three Syrians said they were deported with thousands of others. A man from al-Hamediyah who said Turkish border guards intercepted him 11 times between September and January said that he was usually deported with about 500 other people. However, he said that on one occasion, in January, the border guards gave the people they had intercepted trying to cross from Syria numbers and his was 3,890. He said he was one of the last to be put on buses and taken to the border.

Many people referred to two deportation points that they said were between 10 and 30 minutes’ drive from the security posts where border guards had held them: one was an informal border crossing at Hatya, and the other was a small dam on the Orontes River called “Friendship Bridge.” Human Rights Watch obtained satellite imagery of both crossing points and of four security posts in the immediate border area where asylum seekers said they crossed into Turkey.

A woman from Hama governorate who repeatedly tried to cross the border said she was deported six times during the first two weeks of February with groups she estimated to be between 50 and 600 other Syrians:

The second time, on around February 4, the border guards took us to a military post and put us in a big tent with 200 other people they had already caught. Four hours later, at about 8 a.m., they put us in large buses and drove us to the Friendship Bridge. There they told us to get out and walk across the river back into Syria.

The satellite imagery Human Rights Watch obtained confirms there are gaps in the wall the full length of the Orontes River, west of the Syrian town of Salkeen, and at various points between the southern tip of where the river meets the border and the Hatya border crossing.

Deportations from Antakya

Three Syrians said Turkish police had deported them or relatives from the town of Antakya, about 20 kilometers west of the Syrian border.

A man from Deir al-Zour governorate said:

I crossed the border at night with my wife and two daughters and about 20 other people in late December 2017 near the al-Dureyya [displacement] camp. The border guards didn’t find us. The smugglers took us to their house in Antakya, about two hours’ drive away. There were 20 other Syrians already there and they told us they had also crossed from Syria that night. Not long after that, Turkish police arrived at the house. They took all of us to a police station and held us there until the next morning. They took our fingerprints and photos. Then they took all of us in police vans to the border at Bab al-Hawa and sent us back to Syria.

A man from Hama governorate described what happened to his wife:

The Turks sent my wife back from Antakya twice. She told me everything that happened. The first time was a week ago [about February 10]. The smugglers drove her and about 10 other people from the border near the Orontes River up to Reyhanli and from there they drove to Antakya. They reached the edge of Antakya at about 6 a.m. Turkish police shot at the car’s wheels to force it to stop. They beat the driver and immediately put my wife and the others in a police van and drove them to the border at Bab al-Hawa.

My wife crossed again four days later. The smugglers took her and about 10 others to a small house in a Turkish village near the border and then drove to a house in Antakya where there were already about 50 other Syrians who said they had arrived that night. Suddenly Turkish police arrived, at about 7 a.m. They wrote down their names and took photos. They put them in a big truck and took them to the Bab al-Hawa crossing. They held them there for the whole day and then sent them back to Syria.

Shootings by Border Guards

Nine Syrians interviewed described a total of 10 shooting incidents by Turkish border guards between September and March in which they said 14 people were killed and 18 injured.

In mid-February, a man from Deir al-Zour governorate said that in the previous five weeks he had tried four times to reach Turkey with his wife and five children. The first three times, he said, Turkish border guards deported them. The fourth time they turned back because Turkish border guards shot at their group as they approached the border:

A few hundred meters from the border near the al-Dureyya [displacement] camp the Turks suddenly started shooting at our group. They killed an 8-year-old girl and injured two men, one in a leg and the other in the stomach. I helped the man shot in the stomach turn back with the rest of us while the others carried the girl and helped the other man. Later the smugglers told us that a 13-year-old girl in another group trying to cross at the next time had also been killed during the shooting.

A man evacuated with his wife and baby from Aleppo in late 2016 said he unsuccessfully attempted to cross with them to Turkey three times near the al-Dureyya camp in September 2017 and January 2018 and was deported with hundreds of others the first two times. During the third attempt, in January, he said:

The border guards shot at us and injured my wife in her stomach and leg. She was pregnant and the baby died. They also injured two men and a 5-year-old boy, who was shot in the leg. We took my wife to a hospital in Syria near the border. Her heart stopped twice, but she lived. They couldn’t operate on her, so they sent her to Turkey through the Bab al-Hawa gate for surgery. They amputated her leg and removed her womb. They didn’t let me cross with her but a few days later a smuggler helped me and my daughter cross to Turkey.

Human Rights Watch also spoke with a doctor in a Syrian hospital near the Turkish border west of the town of Idlib who said that between August 1 and February 16, the hospital had received 66 people with gunshot-related injuries who said they had been shot while trying to cross the Turkish border.

Conflict and Humanitarian Crisis in Idlib governorate

According to the UN, about 2.65 million people are currently in Idlib governorate, over 1.75 million of whom have been displaced from elsewhere in Idlib or other parts of Syria, including almost 400,000 displaced since December. Civilians in Idlib have faced years of conflict. In September, Russian and Syrian forces began a fresh offensive in Idlib, three days after Russia, Iran, and Turkey had agreed to a ceasefire and “de-escalation” zone in the province and parts of Hama and western Aleppo. Human Rights Watch documented that attacks in September struck markets and populated residential areas and caused thousands of people to flee to displacement sites near the Turkish border.

Hostilities in Idlib halted on October 8 after Turkey deployed monitors there, but restarted in late December. In January, the Russian-Syrian military alliance carried out airstrikes to support Syrian ground troops. Some attacks involved prohibited weapons and targeted hospitals.

On January 21, Turkey started a military offensive in Kurdish-held Afrin, also putting displaced civilians at risk. Turkish and Kurdish forces have shelled each other on either side of Syria’s Atma displacement camp, on the Turkish border, which shelters 60,000 people.

Witnesses said that on February 6, during the fighting, shells hit the camp, killing an 8-year-old girl and injuring seven other civilians.

Human Rights Watch interviewed seven displaced Syrians about the incident. They all said it left their children terrified of the shelling and unable to sleep.

A father of seven children from Hama who lived close to where the shell landed on February 6 said:

I was there when it happened and rushed to help. I heard a young girl had been killed, but I only saw two who were injured. One had lost an arm and a leg and the other was blinded. I was so scared the same might happen to my children, we fled the camp and went to live in a field near the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. But we couldn’t stay there all alone, without help, so we had to come back to the camp. We are all scared now, all the time.

A father of four children said the incident had so shaken his family, he had returned to his still conflict-riven home town of Kafr Zita in Hama governorate because all other displacement camps in Idlib were full. As his house had been destroyed, he said, he was living in a field on the edge of the town and struggling to survive: “There is still shelling here but if we die, it’s better to die at home.”

Human Rights Watch also spoke with five Syrians who had been repeatedly displaced in recent months within Idlib to escape the shifting front line and who, as of mid-February, were living as close as possible to the Turkish border in the hope of escaping the fighting.

The UN says that since December, the violence has displaced at least 385,000 people who have joined 2.65 million other civilians, including 1.35 million civilians displaced in the past few years.

In mid-February, Human Rights Watch interviewed two aid officials working in Idlib governorate. One summarized the dire humanitarian situation:

There is no more room anywhere for people displaced in the past few months. Displacement camps are completely full and we [humanitarians] do not have the resources to properly address basic needs of water, food, heating, health care, and education. Rent has skyrocketed so people end up living in the tens of thousands on the edge of towns and villages in fields in makeshift camps. There is simply no way the aid agencies can help all these people. At best they can give very limited help once in a while to some of them, and it is not done in an organized way. There is suffering everywhere, in every camp and in every village.

The 56 displaced Syrians in Idlib that Human Rights Watch interviewed, including 42 displaced by the recent violence, all described the extremely difficult conditions they had faced in Idlib in previous months. The newly displaced said they had heard that displacement camps were completely full and that they could not afford to pay the extremely high rents in the towns and villages in the area. They ended up living in waterlogged fields across Idlib governorate, often with other families in makeshift tents made from sacks and other material sewed together, because they could not afford to buy proper tents.

They said they struggled to find food and had to pay high fees for water, delivered by trucks. They either had seen no one from an aid agency, or those who had, said they were unable to help or had promised help but hadn’t returned.

Turkish authorities have allowed Turkish and international aid groups based in Turkey to cross into Syria and join Syrian aid groups to distribute tents and other assistance to Syrians in camps in border areas. Human Rights Watch said that allowing much-needed cross-border aid is important, but does not absolve Turkey of its obligation to allow Syrian civilians fleeing fighting to seek protection in Turkey.

EU Silence

Human Rights Watch has documented that, since at least mid-August 2015, Turkish border guards enforcing the country’s March 2015 border closure have deported Syrians trying to reach Turkey. In April and May 2016, Human Rights Watch documented Turkish border guards shooting and beating Syrian asylum seekers trying to cross to Turkey, resulting in deaths and serious injuries, and sending those who managed to cross back to Syria. In February 2018, Human Rights Watch reported on further killings, injuries and pushbacks that happened in the second half of 2017.

On May 20, 2016, Human Rights Watch called on UN member states and UN agencies attending the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul to press the Turkish authorities to reopen Turkey’s border to Syrian asylum seekers. But neither the European Commission nor any European Union member state – or any other country – has publicly pressed Turkey to do so, while UN agencies have also remained publicly silent.

The world’s – and in particular the EU’s – silence over Turkey’s breach of the cornerstone of international refugee law condones Turkey’s border abuses.

The EU’s failure to take in more Syrian asylum seekers and refugees also contributes to the pressure on Turkey. The EU should swiftly fulfill its own commitments to relocate Syrian and other asylum seekers from Greece and, together with other countries, it should also expand safe and legal channels for people to reach safety from Turkey, including through increased refugee resettlement, humanitarian admissions, humanitarian and other visas, and facilitated family reunification.