What happened to the billions that Brussels pledged to Turkey to keep refugees out of the EU

Via The Black Sea – By Craig Shaw, Zeynep Şentek & Şebnem Arsu.

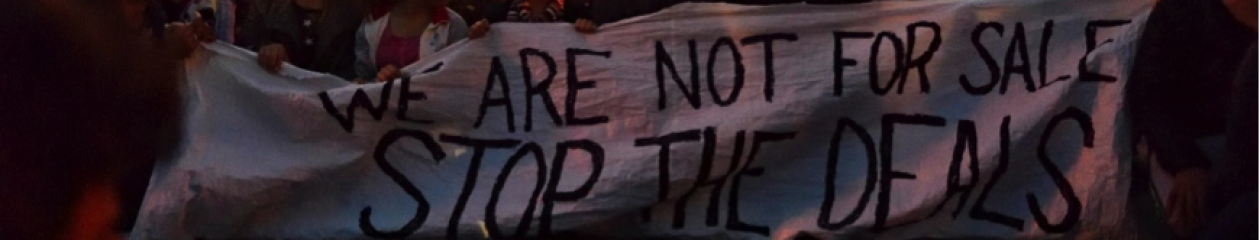

The ending of Europe’s refugee crisis was built on a legally dubious, three billion Euro deal between the EU and Turkey in 2016

With the recent announcement of a further three billion Euro pledged for Turkey, the existing deal is not as successful as the EU publicly states: NGOs have been harassed and fined, there is little public accountability on how money is spent, and many infrastructure projects are only just beginning

Meanwhile, despite requesting to extend the agreement, Turkey is already crafting a “counter narrative” to send refugees back to Syria.

A ‘Billions for Borders’ report for EIC Network, with additional reporting by John Hansen (Politiken), Emilie Ekeberg (Danwatch), Margherita Bettoni (The Black Sea), Hanneke Chin-A-Fo (NRC) Francesca Sironi (L’Espresso).

In 2015, the fighting in Syria had reached a nadir and caused a mass exodus of refugees from the country.

With their homes destroyed and their lives threatened, many thousands of men, women and children fled the violence for relative safety in neighbouring countries.

Since the start of the conflict in 2011, at least five million Syrians have crossed into Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. Some stayed in these border countries, while others travelled onward, attempting to access the EU by land or by sea, where they often risked their lives.

While the images of Alan Kurdi, the three-year old child dead on a shores of Muğla, Turkey in 2015 prompted a temporary outpouring of empathy around the world, it did little to lessen the fears in Europe. The prospect of an increased refugee population in many countries caused a political crisis for its leaders, as anti-immigration sentiment began to rise and far right groups threatened to make gains in elections.

But in March 2016, a statement appeared on the European Council’s website. It declared proudly that the EU and Turkey “had decided to end the irregular migration” and “break the business model of the smugglers” by offering “migrants an alternative to putting their lives at risk”.

The nine-point plan – known as the EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRiT) – stated that Turkey, overburdened by nearly 2.5 million refugees, would implement stricter policing of its land and sea borders with Europe to stop refugees entering. Turkey also agreed to accept the return of any future asylum seekers who made it to European shores.

In return, the EU made big promises to Ankara. It would resettle one Syrian refugee in Europe for every one that Turkey accepted, reinvigorate the stalled EU accession talks for Turkey, by agreeing to discuss the opening the new chapters, and liberalise visa rules for Turks.

The highlight was a six billion Euro pay-off. The cash would help pay for emergency food and clothing, but also much-needed longer term solutions, hospitals, schools and employment opportunities, for not only the Syrians now trapped in Turkey, but also the Turkish communities struggling to adapt to its new neighbours.

The EU made a further announcement two weeks ago. It had completed the first phase of FRiT and declared the three billion Euro project a success. It would now start work on the second phase: two more years and another three billion Euro.

However the Billions for Borders project by The Black Sea and its partners in the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network analysed this deal and found a number of problems: a lack of transparency, harassment by Turkey of the NGOs implementing the deal, and nearly half of the long-term projects barely underway. Meanwhile senior political figures in Turkey, including Erdoğan, are already talking about sending refugees back to Syria.

Since Turkey deal in 2016, EU states accepted “only 12,000 refugees”

The EU’s three billion Euro ‘Facility’ was to show that it cared about refugees.

Although the new arrangement kept millions of displaced people within Turkey, under a questionable and unpublished legal framework, the money was to help pay for both their short-term and long-term needs.

On paper, the ‘Humanitarian’ aid – just less than half of the three billion Euro tranche – is run by the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) within the European Commission and provides emergency food and cash provisions, health services and temporary education programmes.

The remaining 1.6 billion Euro is for long-term “non-humanitarian” projects and is under the purview of the European Neighbourhood Policy And Enlargement Negotiations – DG NEAR. It allocated money for badly needed hospitals and schools, the hiring of teachers and doctors, employment programmes. This also included the resettlement of Syrian refugees in the EU from Turkish camps.

This key aspect of the arrangement failed very early on. Despite a 60 million Euro grant to the Turkish Migration Authority, the institution helping to implement the policy, in the two years since it was active, barely 1,200 refugees have been returned to Turkey from Greece. For its part, the EU has been lacklustre in this area, too – collectively, member states accepted only 12,000 refugees under the same programme during this time.

Though high birth rates and ongoing arrivals pushing the refugee population in Turkey from 2.5 million, when FRiT was agreed, to more than 3.5 million today, the EU appears unconcerned with the silent dropping of one of the most crucial aspects of its arrangement with Turkey.

The Black Sea obtained copies of secret minutes of the Steering Committee meetings, the oversight body made up of representatives from each member state, as well as key figures from the European Commission. The committee is tasked with tracking the progress of FRiT and designating funding.

The minutes, which the EU classifies as confidential, reveal that no member state raised the question of how to increase the resettlement of refugees to the EU from Turkey.

On each occasion that the issue was mentioned, according to the documents, the committee simply acknowledged the lack of implementation and then discussed how to divert the funding into other areas of FRiT.

Now, two years after the implementation of this hard-fought agreement, described by the former Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu as “smart bargaining”, the European Commission released a statement declaring it had “lived up to its commitment to deliver €3 billion for 2016 and 2017” and would now “mobilise an additional €3 billion for the next two years”.

Checks made by The Black Sea show that in reality barely half of the first 26 long-term projects have broken gro and many have not properly begun.

Most will not see completion for another two years, with some even scheduled to end in 2021.

EU-funded Schools and Hospitals Barely off the Ground

A priority target for the EU cash is hospitals and schools. FRiT provides 40 million Euro for a 300-bed hospital in the town of Kilis, and another 50 million for a 250-bed hospital in the town of Hatay, both in the south of Turkey near the Syrian border.

Neither appears to have begun construction.

Despite signing the “delegation agreement” with the EU back in mid-November, the Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), which oversees the Kilis project, told The Black Sea that they are still “in the early stages of project preparation” and cannot provide any detailed information other than the brief statement it published on its website.

The French Development Agency, AFD, in charge of the Hatay build, ignored several requests for information. Recent local news reports suggest construction is not yet underway.

The schools fare a little better. The German development bank, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), said the installations of 60 temporary prefabricated schools was currently underway. Of the plan for 39 ‘solid’ schools in 14 Turkish regions, work had begun on eight, but KfW did not comment further on the current progress.

A project to build 50 schools under the World Bank has only been put out to tender by the Turkish Ministry of Education.

The EU Ambassador to Turkey denied the infrastructure projects were running behind schedule.

“We have contracted KfW and the World Bank who are working with Ministry of National Education on education infrastructures,“ said Ambassador Christian Berger, “[and] the AFD and Council of Europe Development Bank with the Ministry of Health on hospital constructions.”

“Both hospitals will be operationally ready by June 2021. The school projects are going on with a schedule; for example, we expect the first schools to be operational by April this year.“

According to the EU delegation in Ankara, and Brussels, the spending of the three billion Euro has been a great success.

“We contracted 72 projects worth three billion [Euro] by the end of 2017. The main focus areas are humanitarian assistance, education, migration management, health and socio-economic support,” Ambassador Berger said.

“€1.85 billion has already been disbursed, meaning the money is transferred to implementing partners. For such a big amount and variety of fields our colleagues worked day and night with their counterparts in UN agencies, ministries, INGOs and NGOs.”

At every committee meeting, however, the Turkey delegation raised the issue of projects moving too slowly, and requested that cash be paid faster. This echoed complaints that the Turkish government voiced in public. In 2016, referring to the slow disbursement of cash, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said “The EU promises and then breaks those promises.”

There is also a curious addition to the list of projects. The Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey, which keeps the up-to-date figures on Syrian businesses, investments and workers since the arrival of refugee population in the country, is contracted to receive 15 million Euro for “strengthening the economic and social resilience of refugees, host communities and relevant institutions”.

It is yet unclear as on which specific projects the agency was commissioned to spend the money. They have not responded to The Black Sea’s request for information.

“No one wanted to say we are giving money to Erdoğan”

In March 2016, at a time when EU leaders were trying to convince member states that the deal was a great solution, the Dutch foreign minister told parliament that the money was “not meant for the Turkish government.”

There was perhaps concern over a public perception among EU citizens that millions would go into helping prop up the Turkish government’s budget, which was suffering from an economic downturn, or into projects with little transparency.

“No one wanted to say we are giving money to Erdoğan,” a Steering committee member told The Black Sea. “Ankara getting the money directly wasn’t part of the agreed upon plan.”

He added, however, that FRiT is “not the normal way the European Commission does business. It was very middle-of-the-night.”

A member of the negotiating team who was present during the finalisation of FRiT, said the two sides were so desperate to shake hands after a protracted negotiation that they walked away without full clarification about its implementation.

In other words, Turkey thought it was getting three billion Euro.

But most on the EU side, including a member of the FRiT steering committee, claim Erdogan’s anger over not receiving the funds is political theatre, and that the arrangement should have been obvious from the start.

“There was never a blank cheque for Ankara,” said Ruud van Enk, task manager in DG-NEAR and now team leader for FRiT. “If there was a misunderstanding, it was Mr. Erdogan’s.”

660 million Euro in EU cash allocated to Turkish Government

So far, 660 million Euro has been allocated to Turkish government institutions, and over 400 million Euro paid.

This contributes to the bulk of the EU’s achievements under FRiT, according to the last budget release.

The numbers suggests that despite Brussels’s reluctance, much of the deal’s success is reliant on big cash. The World Food Programme (WFP), for example, received almost a billion Euro under the “humanitarian” provisions to disburse monthly payments of 24 Euro to 1.2 million refugees. The WFP, like other NGOs, is entitled to up seven per cent admin costs. In this case, it took 70 million Euro for itself.

This remuneration deal with agencies is more problematic given that Turkish NGOs are forbidden from applying for money under ECHO’s humanitarian programmes. Those which do work on FRiT must find a European counterpart to sponsor them, meaning that admin costs are deducted twice.

The 660 million Euro issued directly from FRiT to Turkey goes to three ministries.

Sixty million is for the Turkish Migration Authority (DGMM) to support the return of refugees and migrants to Turkey with “food, health care, transport and accommodation expenses” as well as “logistical equipment” for the agency. In August 2016, FRiT sent DGMM 12 million Euro.

The remaining two Turkey programmes total 600 million Euro: 300 million Euro each to the health and education ministries, mainly for the hiring of teachers and doctors.

So far, 5,486 Turkish teachers have been hired and 813 medical staff by the ministries, according to the second annual report published by the European Commission.

The FRiT team claimed that Turkey does not receive any money up front. The 402 million Euro it has already provided to the ministries are reimbursements, it says, paid upon the receipt of invoices.

This point was reiterated by van Enk in an interview with The Black Sea.

When EIC asked the DGMM to provide copies of the invoices for the 12 million Euro it received from FRiT, however, the authority refused, stating it was “forbidden” under undisclosed EU regulations.

The European Commission told us that it is not in possession of “any documents” justifying the 12 million Euro DGMM received of European taxpayer money.

In its reply to The Black Sea, the EC spokesperson did say that it provided over 10 million Euro to support the construction of a new refugee detention centre in Çankırı province, the 19th of its kind in Turkey. It was not explained whether this forms part of the 12 million Euro or comes from new funds.

Questions regarding the details of the remaining 390 million Euro paid to the health and education ministries, as well as the requests to release documentation showing these expenses, remain unanswered.

The EU Ambassador to Turkey, Christian Berger, told The Black Sea that public institutions were no different than any other international NGO or UN agency when it came to complying with transparency procedures of the EU.

“All expenditures are subject to verification and final audits by independent auditors,” he said. So far, the verification and audits of the EU have not been shared with the public and Turkey seems to be keeping its expenditure details secret.

“Considerable pressure on international NGOs”

One of the most dominant issues raised during the steering committee meetings is the treatment of NGOs and agencies by the Turkish authorities and representatives of EU member states talk often of the “considerable pressure on International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs)” by Turkey.

NGOs are essential for the six billion Euro deal to work. The EU’s regulations permit only Europe-based organisations to apply for humanitarian funds – and almost all of the emergency aid money is given through this structure.

The meetings detail several concerns over Turkey’s attitude towards NGOs.

European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) Director Jean-Louis de Brouwer said during the steering committee meeting on 8 November last year that Turkish Minister of Interior Suleyman Soylu had a “strict approach to INGOs quoting security concerns.”

Some of these strict approaches used by Turkey include: revoking licenses to practise in the country, slowing the registration process, opting to give licences for only short periods of a few months, and obstructing the issuing of work permits for NGO staff altogether.

These restrictive measures have caused fear in many FRiT partners, it seems. Added to this was Turkey’s decision last year to kick out Mercy Corps and fine the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) – two NGOs involved in implementing several FRiT projects.

The DRC, which never issued a public statement on the fine, and refuses to disclose the amount or how it will be paid, told EIC that it was levied over its failures to obtain work permits for Syrians it had employed as part of its projects.

Declining to go into specifics because of a pending appeal, a DRC employee told The Black Sea that “the fines we received concern the type of contract used for Syrians without a work permit.”

“While DRC aims to comply with national legislation in Turkey, we believed the appropriate contracting arrangement to be through service rather than employment contracts and hence have appealed the fines and are awaiting a decision,” he added.

When questioned about the fine, Ruud van Ennk at FRiT denied any knowledge, and EU ambassador Berger suggested the issue to be raised with ECHO.

Only 34,000 work permits issued to million-plus Syrians in Turkey

Turkey’s decision to financially penalise a FRiT implementing partner is problematic given the slow progress of its employment agency in issuing work permits. The Turkish Employment Agency, ISKUR, is the ultimate recipient of a 50 million FRiT grant, administered through the World Bank.

In the meeting in March 2017, however, the Turkish delegation stated it had issued permits to “10% of the total refugee workforce”. This claim, unchallenged by the committee, appears to be untrue.

Data from the UN’s Refugee Agency – UNHCR – puts the number of registered Syrian refugees in Turkey aged between 18-59, and therefore potentially eligible for work permits, at around 1.75 million. Turkey’s own statistics state that in the past two years, the Turkish Employment Agency managed to issue only 34,000 work permits to Syrians: 13,000 in 2016, and 21,000 in 2017. This is less than two per cent.

A lawyer familiar with the work of the Danish Refugee Council pointed at foreign organisations’ lack of experience and knowledge in functioning through labyrinths of Turkish bureaucracy.

“International NGOs that work in the humanitarian field enjoy several concessions when they want to work in Turkey, but they still need to obtain certain licenses and permits,” the lawyer said in a phone interview, asking not to be named.

“As far as I know, the Danish Refugee Council had put their vacancy ads in false wording, hired Syrian staff and made a procedural mistake, then was fined.”

Other cases of harassment of EU-backed NGOs in Turkey reflect a fragile peace among the parties.

An orchestrated smear campaign in the pro-government media showed how fierce the battle over humanitarian aid delivery could be when Mercy Corps, a leading supplier of goods inside Syria, was labeled as a terror group affiliate.

The US-based NGO, one of world’s biggest humanitarian agencies, shut down its offices in Gaziantep, near the Syrian border, after Turkey cancelled the work permits of all its staff there on grounds that the group illegally transferred money into Syria. Now, one of its two FRiT projects has been shelved before it started.

An international humanitarian aid worker who was familiar with Mercy Corps’s ordeal underlined the seriousness of threats and intimidation.

“The names of some high-level Mercy Corps personnel were all across pro-government media. Confidential meetings the organisation made with government officials to keep their operations going were constantly leaked in the same papers. This was the level of intimidation” he said, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

“They had to leave. Except one project that they’ve completed for FRiT, which was about purchasing a patrol boat for the Turkish Aegean coast guard, they had to cancel a second before it even started.”

Such pressure was not special to Mercy Corps but applied to many more, he claimed.

“No one wants to speak out because if you speak out, you know what happens.”

This atmosphere of fear and secrecy has infiltrated other NGOs: although collectively they receive hundreds of million in public money, most refuse to account for how it is spent or provide any details about their programs.

The Black Sea has contacted all of the organisations who received funds as part of the refugee deal and asked them to explain their projects, deliverables, success criteria and costs. While some replied with partial information, most declined to speak to journalists.

Handicap International, a major NGO based in France, said “they do not communicate with the press”, citing difficult conditions in Turkey. No information exists regarding exactly how it spent almost five million Euro it was given. When pushed for more information, the press officer in the Lyon office replied: “Think whatever you want to think.”

Medecins du Monde, Relief International, and Concern Worldwide, who in total are contracted to receive 25 million Euro, had similar attitude and refused to comment on their work in Turkey or how they spend the funds they receive from the EU despite repeated attempts.

In fact, Concern Worldwide falsely claimed it was “working in a war zone”.

Organizations like the World Health Organisation, International Medical Corps and World Vision, which get 38 million Euro for their projects in total, ignored several requests for information. Others such as IOM, GOAL and Search for Common Ground gave very limited information and did not answer specific questions.

Michael Rupp, the counsellor to the EU Delegation of Turkey, reassured that EU taxpayers money was in safe hands.

“It’s very difficult to spend EU money,” he said. “We look into every dime.”

Turkey: Developing “Counter-Narrative” to See Refugee Return

The meeting documents obtained by The Black Sea and EIC suggest heavy PR games between the EU and Turkey are now underway.

From November until the beginning of 2018, the EU contracted over a billion Euro in non-humanitarian FRiT projects in time for the two-year anniversary.

At the most recent meeting, in March, every member state “expressed deep dissatisfaction” at the unilateral decision to commit to the next three billion Euro funding before they had seen an “implementation report” – a requirement under the committee’s “Rules of Procedure”.

The European Commission ignored their protests and made the announcement public five days later.

The motive, however, was not the urgency to assist refugees, but the desire to declare FRiT a success in order to help European leaders avoid a confrontation with President Erdoğan at the Varna summit that would take place at the end of March 2018.

To soothe those with complaints, the commission chair told member state reps that the quick timing created no need for an “operational decision” on the money. This was because the “real deadline for providing new funding is September [2018],” he said. There was no need to panic.

The Turkish government, for its part, has revelled in the opportunity to show its supporters that Erdoğan’s combative attitude and strongman tactics towards the EU are a sign of resilience.

MPs from Erdoğan’s party – the AKP – have attempted on several occasions to claim credit for FRiT’s work. Ministers – including the AKP MP from Kilis and prime minister, Binali Yildirim, visited regions where hospitals and schools are set to be built to praise its infrastructure work, often conveniently declining to mention the EU as a source of funds, or declaring Erdoğan as the instigator of the projects.

Privately, the EU believes Turkey has other intentions on its mind.

At the most recent meeting in March, an EU representative told the committee that while Turkey reflects on a more sustainable approach towards refugees, it is, in parallel, developing a “counter-narrative” whereby “conditions were met for a certain number of refugees to return home”.

This tactic has already begun to manifest itself in public. In recent months, several senior Turkish political figures, including Erdoğan, and even his wife, made comments announcing that Syrians might begin to leave Turkey.

In January, Erdoğan said that Turkey is now “taking steps to send 3.5 million of our Syrian brothers and sisters to their homeland as soon as possible.”

The following month, Emine Erdoğan, the first lady, told a humanitarian conference in Istanbul that, “Once security and stability are established, new refugee flows would stop, our Syrian brothers, God’s Will, will return to their countries,” and added, “God willing, after the Operation Olive Branch, it is expected that 500,000 Syrians will go back to Afrin”, referring to the Syrian border district where Turkey conducts military operations against Syrian Kurdish fighters of the PYD. The EU recently warned that Turkey’s offensive should not become “disproportionate”, seen by some parliamentarians as a weak condemnation.

Returning Syrians to their “homeland”, however, might not be so clear cut. A study conducted last summer by the Istanbul-based Human Development Foundation, INGEV, showed that 52 per cent of Syrian refugees in Turkey wish to say in the country, and 42 per cent would like to reach Europe.

But for now, with the borders to the EU heavily guarded and the new three billion Euro deal agreed upon, the EU can delay the fate of 3.5 million people, many without homes or jobs, for another two years.

Opening photo: Syrian Kurds’ temporary settlements in Sanliurfa, Turkey, in a building under construction after the refugees crossed into Turkey on 9 October, 2014. (Photo by Ozge Elif Kizil/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

This article was originally published by The Black Sea on March 30 2018.