A report from the contested borders in the Aegean region

By Sabine Hess and Gerda Heck, June 2016

[updated in September 2016]

After months of massive refugee movements that have breathtakingly struggled their way towards Northern Europe last year, European Union member states have started to launch diverse actions and measurements to regain control. A coalition of Eastern European states led by Austria proclaimed the closing of the Balkan route in March this year that led to massive national re-bordering activities and the blatant construction of fences. Additionally, the EU commission together with Germany set up a so called action plan with Turkey and pushed the so-called “EU-Turkey Deal” via a “statement” on 18 March 2016. And indeed, the numbers of those still arriving in Austria and Germany, daily using the Balkan route for their flight/migration projects, have decreased drastically compared to the summer months of last year. However, we all know that the global refugee population is not on the decline, given the old and new, simmering and open wars, as well as the destruction of nature and it’s resources. What the present regional and EU-European professed solutions are doing and, in particular, what the EU-Turkey Deal is doing, is an externalization of border controls and thereby an externalization of the “pressure” on Greece and Turkey. The deal particularly transforms them into Europe’s border guards and parking lots all the while Turkey itself being entangled in a gory civil war in the East! Greece, on the other side, has been subjected to harsh austerity politics since 2010, accompanied by a heavy social and political crisis, and was not willing and/or able to install an asylum system consistent with EU standards for at least the past 15 yeas! On the contrary, both countries have focused on transit as a political strategy of migration governance up to now.

In the following, we will take a look at the EU-Turkey Deal and its repercussions on Greece and Turkey, focusing on the effects of the deal on refugees, and present some preliminary considerations on how to theorize and understand the attempts of EU-Europe to regain control over the movements of migration. We draw on our recent experiences during a first four-week field study in Chios and Izmir at the end of April and beginning of May 2016, that we were able to carry out in the context of the transregional research project on the „Restabilization of the Border Regime“ at the Institute for Cultural Anthropology in Göttingen (Germany), funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. The motto of the EU’s current restabilization attempts and of the Northern European states is: out of sight, out of mind. This has worked relatively well ever since the past 15 years of externalizing border controls as one of the main maxims of the EU-European border politics – even though the movements of migration have again and again been successful in attracting public attention.

Right now, however, we are confronted across the board with multidimensional re-bordering efforts by the EU and its bodies as well as by the nation states with partly different rationalities and directions as concerning the vision of “Europe” – all in all with disastrous effects. And it is these effects that we would like to scrutinize with this contribution. In doing so, we will draw on very recent impressions of our field study in the Aegean region, for which finding the right words is not an easy task. To begin with, ‘unsettling’, seems to be the most appropriate. The pope almost took the words right out of our mouth when he accusingly asked while receiving the Karlspreis: „What is going on with you, humanist Europe?“

The basic course in Postcolonial Theory teaches us that the history of this humanist Europe has always been closely linked to racist and missioninzing disciplinary and eliminatory projects. Nonetheless, different social movements – like the workers’, women’s or migration movements – have been successful in enforcing a certain degree of social state, juridification and suable protection of human dignity during the past 150 years. This dignity is currently bogging down in the dust of the Greek islands, without anybody severely denouncing this state of affairs despite the manifold critiques of the “deal” and its effects as “reckless” and “illegal” by human rights organizations, EU parliamentary delegations etc.

The Deal

Two cornerstones of the EU-Turkey Deal can be identified, a deal that is “close to being illegal” according to remarks by European politicians (!). To denote the deal as a “state-operated human trafficking project” – as only recently termed by an European initiative of writers and researchers – is dead on target, whereas the Syrian refugee has become a commodity in this horse trade. Turkish lawyers have also called it the “gravedigger of the Geneva Convention and the right to an individual asylum claim”.

In short, the agreement allows, in the first place, to deport all migrants back to Turkey, who arrived on the islands after 20 March 2016 by an asylum fast track procedure, unless they can proove that Turkey is not a safe third country for them. Thereby, only vulnerability criteria count, meaning that there is no inquiry of individual reasons for asylum anymore. The deal is based on a recently revised Greek and Turkish asylum law and an older readmission agreement between the two countries, but lacks of an international agreement. In return, the EU promised to receive one Syrian from the Turkish camps for every deported Syrian in the so-called 1:1 procedure. So far, only 802 Syrians have been resettled from Turkey to the EU until July 2016, since many EU-countries refuse to admit them.

Whereas the deal has been declared to be a “huge humanitarian solution”, which would put an end to the smuggling business and provide legal ways to enter the EU, it primarily is a machinery of systematic disfranchisement. For this purpose, it takes the arriving refugees on the islands hostage, in order to use their state of being stuck in limbo as a deterrent. So far, this seems to be the one and only outcome of the deal that works out – the rest, the relocations and the returns from the Greek island to Turkey (under 500 up to July 2016), are rather very low. But nonetheless, the effects of this accelerated EU externalization politics should not be underestimated and can be summoned up in the following four points:

- a systematic disfranchisement, which prefigures the removal of any kind of suable international protection;

- an extensive fragmentation of the European legal space with absolute arbitrary law standards for one and the same migrant group, depending on when and where they are, whether in Turkey, on the Greek islands, on the Greek mainland, in Hungary, Austria or in Germany; In this respect, the deal produces for Europe the so called “island solution” Australia has been administering for a long time. Alison Mountz describes it in “The enforcement archipelago: Detention, haunting, and asylum on islands” (2011) as a political strategy to subvert juridical standards.

- an expansion of humanitarian actors, who try to govern and to cushion the hardship, whether parallel to or entirely instead of the state. Regarding migration governance, these NGOs often work in good collaboration with transnational political actors as the European Union or Frontex.

- a tremendously growing transit economy, from which not only private actors, but also NGOs and Charity Organizations benefit, for instance in terms of receiving huge donations; the camp-regime is also part of this ecomony.

Turkey

The main effect for Turkey is the fact that with the deal the transit is blocked. Accordingly, Turkey is starting to prepare for officially becoming an ‘immigration country’ for Syrian refugees, although all our conversation partners told us that they are just awaiting the failure of the deal. So primarily, we were confronted with an integration discourse, while only a few groups – mainly lawyers and activists – were trying to observe the deportations from Greece and do border monitoring.

Let us start on the Syrian-Turkish border, where about 240.000 Syrians are residing in a half-closed camp regime. German chancellor Angela Merkel recently praised them as a model for all of Europe. When talking to Syrians in Gaziantep, they told us that only those who have no other means enter these camps voluntarily. At the same time, the Turkish border police has closed the border towards Syria last autumn and defends the border from time to time, if necessary, by shooting and killing refugees, as Amnesty International listed in a recently published report.

Behind the border on Syrian soil, Turkey already starts to implement a de facto buffer zone, in which currently tens of thousand of refugees are stuck only receiving supplies on a very provisional basis by the Turkish IHH (Humanitarian Relief Foundation). Syria has turned into an open jail in the last couple of months, which can only be left towards Turkey with tremendous exertions and a lot of money, as refugee women, who have made it only recently, told us. In order to reach Turkey, they had to overcome several border barriers from the “Islamic state” and other groups and afterwards a last one to Turkey.

Thereby, the hypothesis that the men often leave first and risk the dangerous journey in order to get their women and children afterwards to join them via family-reunification, is in this sense untenable. We met innumerable separated families, who had already partially made the way towards Germany during the „summer of migration“ via the virtually state-organized transit alongside the Balkan route. Others were currently stuck on the Greek islands, among them numberless women with their children who had been sent ahead.

But Turkey as well, is described as an open jail by politically active refugees, NGOs, and lawyers. Until recently, Turkey followed an “open door policy” towards Syrian refugees (currently there are around 3 Million Syrian refugees present in Turkey), who in the country itself, found themselves in a guest status with very limited rights. This is mainly caused by the UNHCR and Turkish asylum politics. Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, but applies a geographical limitation, which means it only accepts European citizens as “convention refugees”. All non-Europeans have to apply to the UNHCR in order to receive the refugee status, who carries out Asylum procedures for non-European refugees parallel to the Turkish state. If granted refugee status, asylum seekers are eligible for resettlement. Many refugees hope to make use of this resettlement program mainly towards Canada, the USA, or Scandinavian countries. Unfortunately, in many cases, this procedure endures up to six or even more years. During that period, they are obligated to remain in one of the thirty so-called satellite cities all over Turkey. According to a lawyer we met, more than 250.000 recognized refugees are currently waiting in Turkey to be resettled.

However, Syrian refugees, as being civil war refugees and having a temporary protection status in Turkey, are excluded from the UNHCR asylum procedure. In 2013, UNHCR also suspended asylum applications from Afghans, citing a backlog of cases. Only the most vulnerable, such as unaccompanied children or chronically ill applicants, can become resettled. According to our conversation partners, due to the tremendous increase of asylum seekers the UNHCR might consider to suspend the applications of all nationalities and restrict the access to the resettlement to vulnerable cases.

Since 2014, things have changed with the foundation of an asylum and migration authority – the so-called DGMM, resembling the German BAMF – and a new asylum law. The EU was demanding these two amendments over the last ten years in the context of the pre-accession talks (see reports by Cavidan Soykan). This now serves as a prerequisite to proclaim Turkey a „Safe Third Country“ or a „Safe First Country“ of asylum. However, our research shows that the old system is still in effect, only now with a number of asylum seekers twenty times higher.

Syrian refugees can register for a so-called „temporary protection status“ that is located outside of the asylum law. This means that through UNHCR’s politics, which refer to vague clauses of the Geneva Convention in case of a „mass influx“ situation, as well as through the Turkish asylum law, Syrians are bereft of individual asylum. In combination with the EU-Turkey deal, this means that they are left with Turkey and an uncertain, temporary and highly precarious status with reduced social rights – if they ever get to take their turn to register at all: the registration department of the police appears to function like the overcharged social security office in Berlin, providing only a little amount of officers for the task. In Izmir, a city of three million people with a Syrian population of about 150,000, there are two officers with a capacity of 100 registrations per day. For this reason, many are not registered at all and find themselves outside of any legal entitlement whatsoever, running the risk of being brought to one of the camps along the Syrian border with every single police check. Along these lines, the camp system serves as a permanent threat.

The temporary protection status actually encompasses a work permit, minimal health care, and the possibility of children to access the school system. The emphasis needs to be placed on „actually“, since all our interview partners haven’t seen any work permit up to today, and according to them, schools have eagerly been finding excuses not to admit Syrian children, and a translator always needs to accompany patients when seeing physicians and going to hospitals, since otherwise refugees are denied access there as well.

The consequence is an outrageous precarization and impoverishment with well-known elements (see Baban/Ilcan/Rygiel 2015): high work exploitation and child labor, with bad to disastrous living conditions and health care, as well as a first generation of Syrian children without any school education. The temporary protection status only seems to minimally improve this social condition. This means that in Turkey as well, NGOs and international charities are shooting up like mushrooms, distributing food, clothes, medication, and hygienic products. The AKP government seems to deliberately deploy this political style instead of extending rights, supported by a well-organized armada of Islamic charities. These religious relief organizations have a crucial role in AKP’s ethnic- and religious-oriented paradigm of the migration management, which operates through a network of state institutions, party cadres, municipalities, local NGOs and Syrian organizations.

Returns

While the refugees in the country are facing restricted rights, the situation for the 500, predominantly Pakistani, Afghan, Iraqi, as well as African and Syrian refugees who have been returned back as part of the deal, seems to be serious. Right after their arrival, they were brought to the ‘removal center’ in Kırklareli at the Bulgarian border, where lawyers and the UNHCR were denied access up until recently. After some first visits, lawyers, as well as the UNHCR, unanimously told us that the situation there was „terrible“; minors and whole families confined in small cells, having yard exercise for only 15 minutes after dinner and being bereft of all communication devices. The detained had not been able to contact their relatives for 20 days straight. On top of that, especially the statements of the imprisoned persons about their return are rather reminiscent of government-run kidnapping (see interview with a refugee imprisoned at Kirkareli): all with whom we have been able to speak to until today stated that at the Greek side they neither were informed about an asylum application nor their deportation. Rather, they were brought from camp to camp, from a room to a bus and finally to a ferry without being able to make sense of this proceeding. Many men reported to us about severe strokes by Greek border guards on their way from the camp to the bus. Lawyers found massive contusions and bruises. According to them, families have been walked off in handcuffs and minors were imprisoned. One lawyer managed to talk to a young woman who had fled with her family from a forced marriage with a Taliban officer and now lives in fear of being deported as far back as Afghanistan – with good reason, since rumors spread that in this Turkish prison as well, the word “asylum” seems to be unknown and first chain deportations have taken place. On the other hand, nearly all the refugees we have been able to talk to, during the first weeks after the deal started, were free again and sent to satellite cities. The situation of supposedly „voluntarily“ returned refugees, of whom some exist thus far, is completely uncertain. Currently, UNHCR is negotiating with Turkey and the EU in order to engage in monitoring the return process from Greece to Turkey. The present absence of this monitoring seems to be one of the reasons of the very slow deportation process. Then, however, it is to be feared that the returns will gain momentum with the cordial assistance of the UNHCR, since, as we have to bear in mind, after the first highly medialized returns from Greece to Turkey, they have been stopped on a large scale and only small groups of people are being taken to Turkey.

Greek islands

While the situation in Turkey is thus specifically fraught with tension in a social and domestic political way, the situation of the refugees stuck on the Greek islands due to the deal is disastrous and points to the lies in the EU’s first progress report from 20 April 2016. The report paints a rosy picture, stating that great progress had already been made in juridical as well as infrastructural regards by Greece and Turkey, „to ensure full respect of EU and international law“. We haven’t noticed anything hereof and of the allegedly supporting EU-officials, accept for a big armada of more than 150 Frontex officers, 100 of them staying on the island just in order to supervise the returns. The Norwegian Refugee Council as well, a highly professional global protagonist offering its service of „camp and flow management“ to other NGOs and the state, stated in our interview:

„The recent EU report doesn’t resonate at all with what is happening on the ground. The speed is just cruel and painfully out of step with the capacities of the Greek state. The reception arrangements are shockingly bad. They don’t follow at all international law standards.“

Indeed, what leads to the disastrous situation of the refugees on the islands is first and foremost the camp regime, whereas the big hotspot Vial with over 1,000 places has turned into a military-run closed camp overnight due to the deal. All NGOs as well as the UNHCR have withdrawn from it, criticizing the situation. The two smaller open camps in the city, up to then providing an endurable infrastructure as transit camps for a few days, have gained a different function as effect of the deal, now having to host more and more refugees over the past months. It needs to be remembered that boats with refugees keep on going ashore – not on a daily basis, but still consistently do so.

However, regardless of what camp we looked at – whether the state- and military-run, or the two more open ones, more or less run by the city together with the UNHCR (outsourced to Samaritan’s Purse): concerning medical care, food, blankets, hygiene, space etc., we found that the basic supply situation in all three camps were below the standards that could still be called humane. To add insult to injury, there is a catastrophic information situation with rumors spreading within seconds and none of the many small NGOs nor UNHCR setting about to organize reasonable information politics in order to un-confuse refugees about the deal and their rights. Lawyers are practically absent on the whole island. Of all the EASO-officers, whose task actually should be to shed some light on the situation, none of them were to be seen.

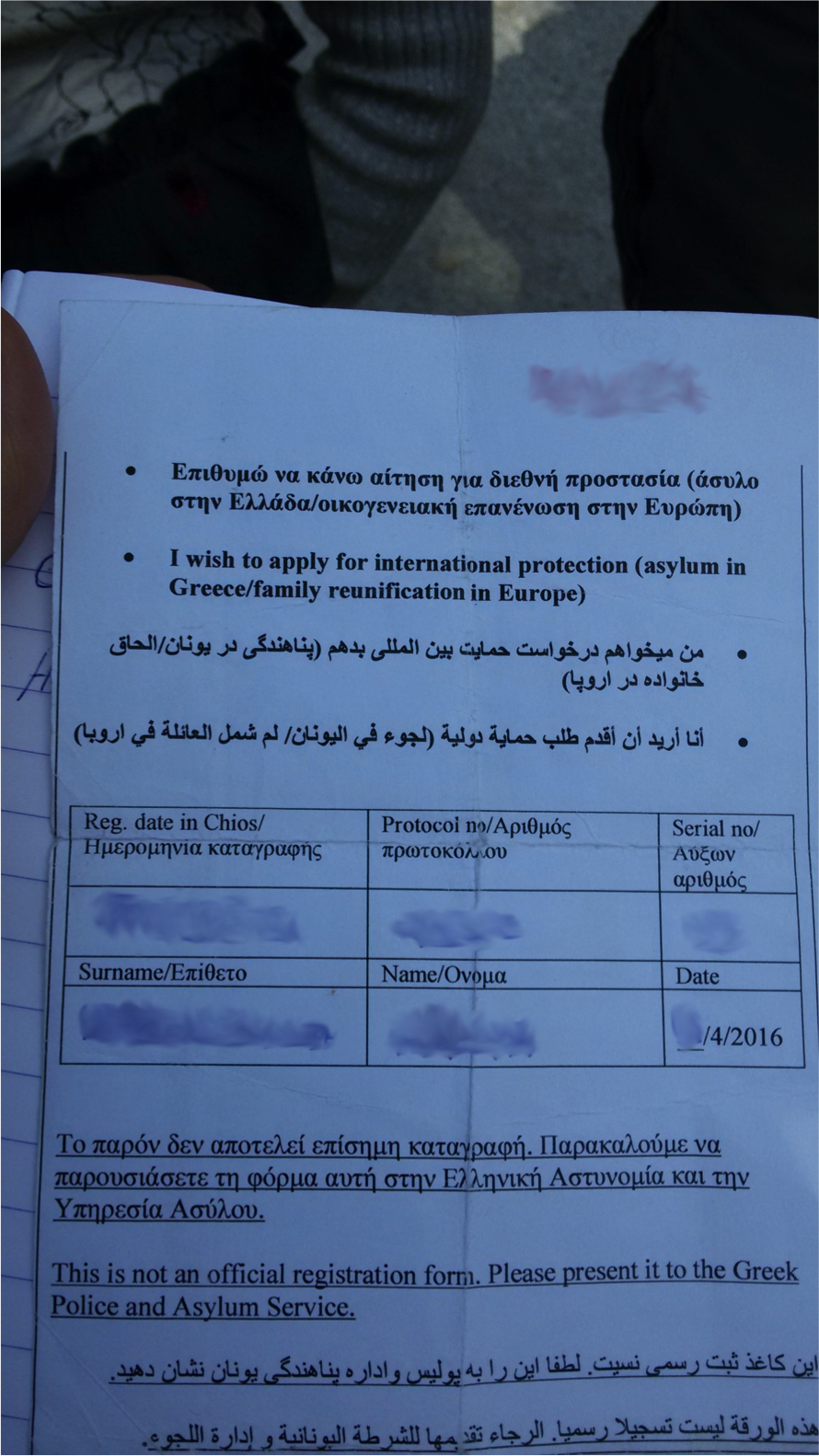

Moreover, we saw all kinds of forms that have been more or less improvised out of sheer necessity by UNHCR and by which – due to the absence of a functioning asylum procedure – refugees can claim their will to someday claim asylum. According to the Norwegians, at the moment of our research beginning of May 2016, only one asylum case official has been present on the island. These strange slips of paper have become necessary in order to equip the refugees with any document in order to protect them from deportation. At the same time, they comprised a catch question: the refugees were asked whether they wanted to apply for asylum in Greece. Since many of them had family members in another EU country and thus precisely did not plan to stay in Greece, they answered „no“. When they were then asked if they wanted to return to Turkey, all of them answered „no“ as well. But, according to the deal, twice a no makes a „yes“. Many refugees as well as courageous camp managers told us about further trickeries of the Greek police or the Frontex officers who are responsible for the first registration and fingerprinting, with names being entered incorrectly or the date of arrival knowingly manipulated. We were also told that, before 20 March – the deadline of the deal – the registration had deliberately been carried out very slowly and then was shut down completely, making sure that refugees had their turn only two days later.

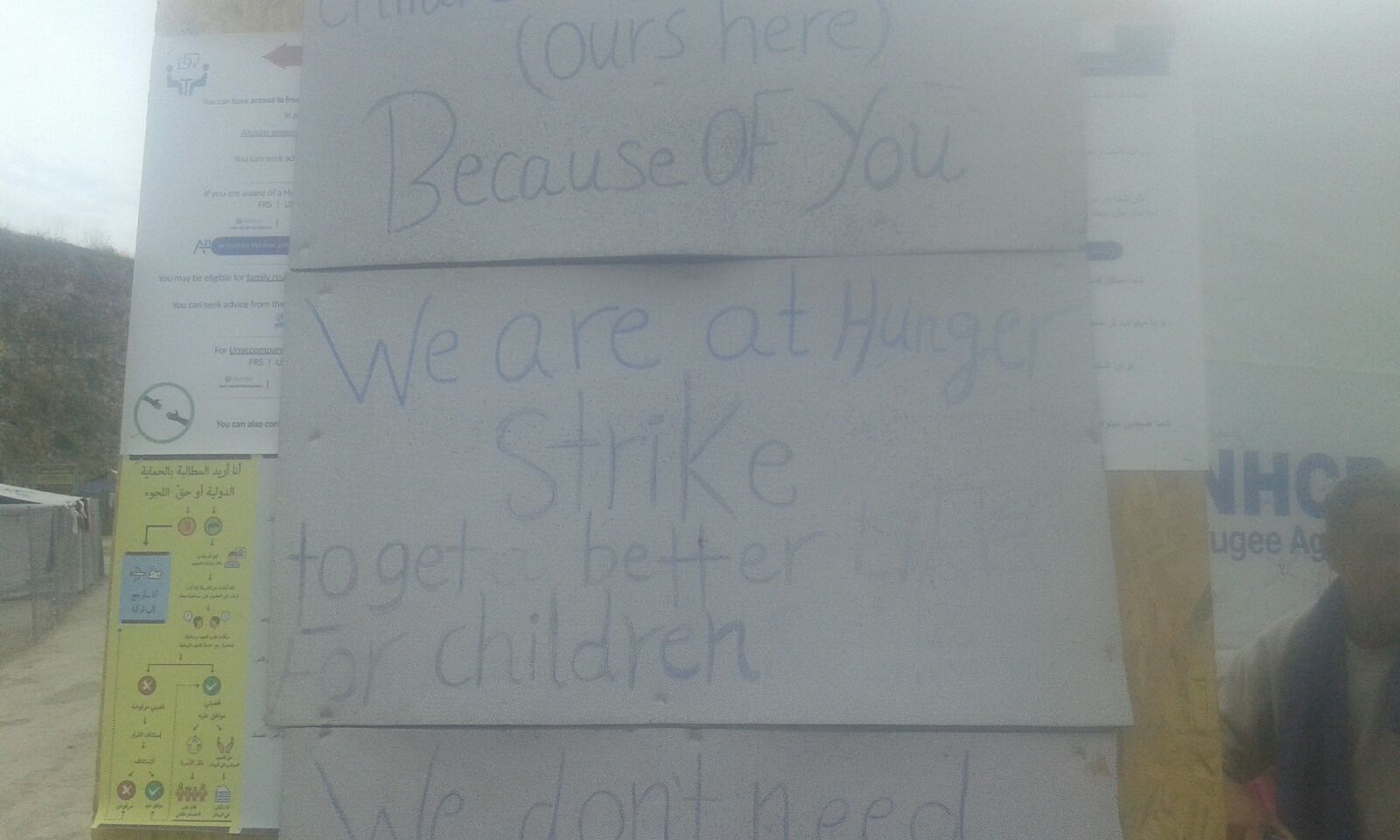

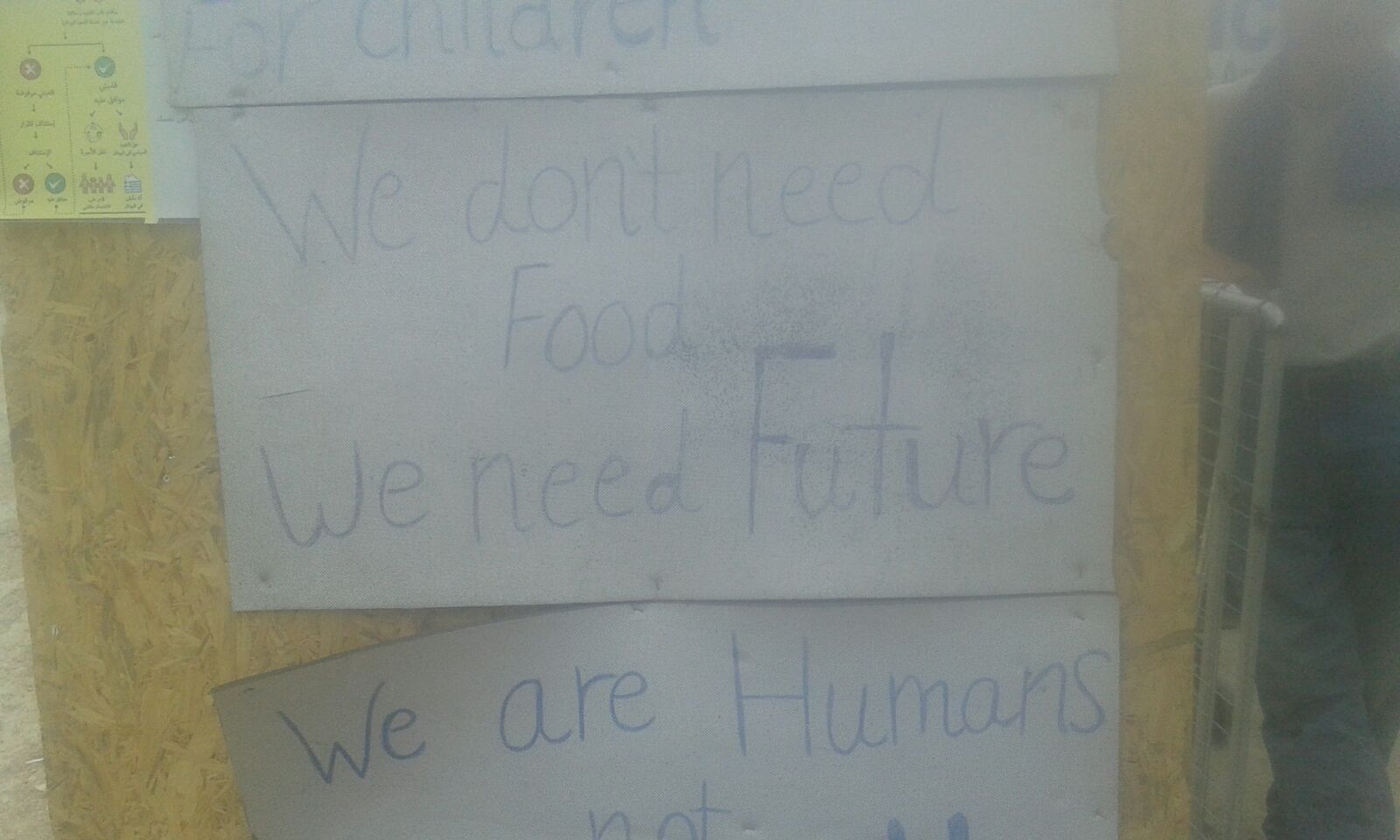

And with every passing day that we stayed in the camp and talked to refugees, hope slowly died a bit more while proportionately more despair could be noticed in the faces of the families, women and children, not knowing how things would continue, what would happen to them, and how long they would have to bear and organize this camp life for themselves and their children. Whereas the proper life in Northern Pakistan, Iraq or Aleppo, to be seen on pictures on the smartphone, showing houses, cars and indeed a bit of luxury, seemed to have emerged from a different planet. And quite some nervous breakdown followed, some claims of children wanting to go home, not wanting to eat the watery soup anymore, served to them by some NGO on a daily basis from a car. In a particularly impressive manner, women depicted how their flight and camp life had changed their bodies concerning the deprivation, noise, bad food, and hygienic situation – particularly demanding situations for women and children –, has weakened and emaciated them and made them look like „men“ – reduced to „bare life“ in the sense of Giorgio Agamben (1998). In opposition to Agamben’s assumption however, this is not to say that refugees do not themselves possess agency, as we will show later in the text. We were very moved by the sheer tenderness with which women and also men took care of their children, forming communities of care, and how those who speak English championed as translators and mediators, trying to canalize the countless NGOs with all their goods to the persons in need. Of course, there was also enviousness and a lot of quarrelling.

Especially the distribution politics of most NGOs establish a dehumanized situation, handing out one glass of milk, a few shoes or some baby milk powder now and then in far too small amounts at some place, leading to knots of people waiting in line, pushing and punching each other. Resources were always too scarce for his or her own day, thus dependency and suppliance were pre-programmed. What camp researchers call a „camp habitus“, was also bemoaned in neocolonial manner by the white supporters when they complained that children in particular sticked to them like a bur and that those who had been turned into passive supplicants tried to act precisely according to this role. However, while many camp studies focus on the residents, the whole fuss rather reminded us of the insights of the studies on humanitarianism: they analyze these politics of charity as an arbitrary and selective „politics of life“, as Didier Fassin puts it (2007), that cements unequal power relations.

We also had the impression that only little was arranged and communicated between the different actors, while the UNHCR, but most notably the local and national state, were notably absent. Frontex alone seemed to offer a briefing once a week for all NGOs and seek after a good cooperation. However, since the situation in the military-run hotspot/detention camp was not very different indeed, since more and more refugees were sent to the open camps in order to collect medicines from the NGOs, and since some Frontex staff members were so overwhelmed with pity that they single-handedly collected blankets and clothes and took them there, one almost needs to assume that the miserable situation is indeed part of a state approach following an escalation strategy directed at EU-Europe. Then again, it points to the complete absence of an asylum administration infrastructure, which Greece has only very hesitantly if at all implemented according to the many EU directives within the past 15 years. Organizing the transit has been the main raison d’état, as Vassilis Tsianos and Efthimia Panagiotidis (2007) were able to work out in the early 2000s in the framework of our Transit Migration research.

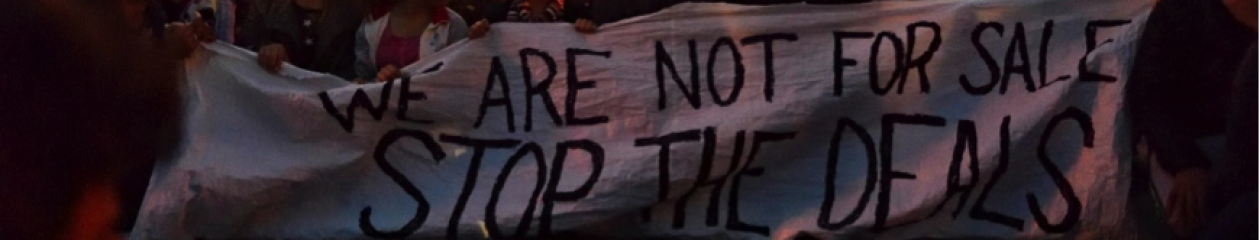

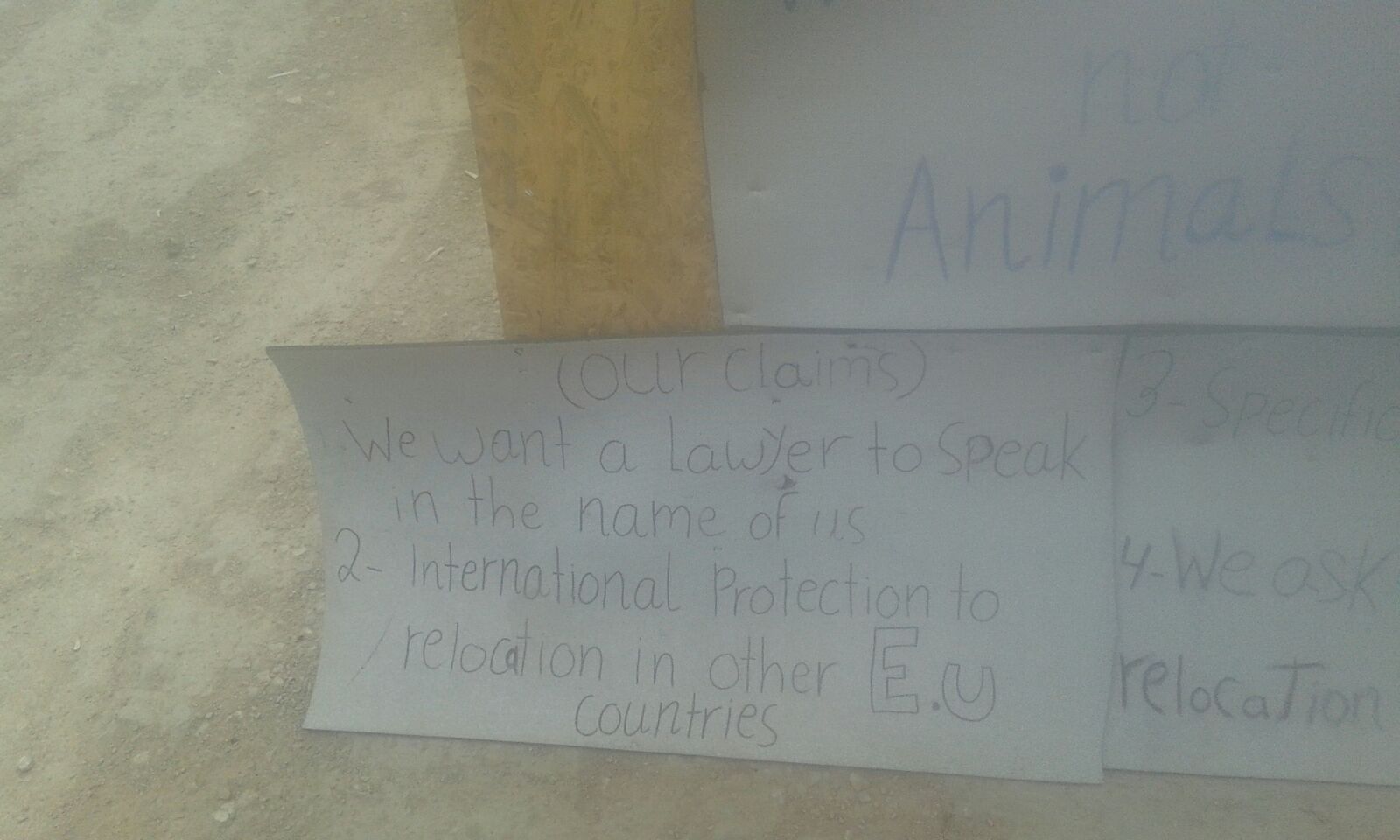

Nonetheless, almost on a daily basis, smaller and bigger protests took place in the detention camp as well as in the open camps. Given the density in the camps and the bad and foul food, in Vial such fierce clashes erupted between refugee groups in March – without the police intervening – that hundreds of refugees, primarily women and families, cut holes into the fence and marched to the harbor where they erected a protest camp. While they were jointly evicted by the use of massive police violence and a furious mob of Greek citizens a few days later, many families have been living in the open camps ever since. Likewise, protests during our stay have lead to Vial being half-open again and to refugees being able to enter and exit. Therefore, quite some fluctuation exists between the camps, and a certain degree of autonomy of migration can be noted, even under the harsh conditions. Indeed, since the refugees have so little to lose anymore, and at the same time many of them have almost set up something like a resistance community throughout the weeks, they probably won’t accept being returned en masse to Turkey. The struggles about border crossings and the right to flight are, in this sense, still to be expected.

All the while, EU-Europe prepares, internally as well as towards the public, for what will happen when the deal with Turkey doesn’t work out, and Erdoǧan orders to decontrol the coast line and hundreds of boats are put to sea again. Just in case, the defensive walls around the islands are already being built up rhetorically. They are meant to become the central registration location – in other words: a deadlock, or an open air detention camp. This will not change much about the lousy conditions on the islands – now already, the refugees are stuck there without any idea about the outcome or where they might end up.

Back at the desktop in our office, these impressions of and experiences in the EU-European borderland – that seems to have been governed, during the last months and after the summer of migration, in terms of the Agambian sense by the continued state of exception beyond the law – appear to be very disconnected from reality. In fact, only a single question keeps haunting us, taking us back to Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben: the question by which “juridical procedures and deployments of power […] human beings could be so completely deprived of their rights and prerogatives [that is, the right to have rights] that no act committed against them could appear any longer as a crime”, as Agamben puts it (Agamben 1998: 97). To follow up these juridical procedures and political dispositifs, the ethics and normalizing strategies, indeed reaching as far back as the colonial history of this Europe, including the struggles against them, all will accompany us for the next years during our critical migration and border regime research. In the process, it is essential to be in the field ethnographically, to dive into the local situation and, if possible, to listen to and watch the different actors. First and foremost, however, one needs to be astonished again and again by the movements of migration – particularly by the excess of desire to want a different, a better life.

Epilogue

In the meantime, in September 2016, things have been changing again: the hot spots on the main five islands in the Aegean Sea that have been already laid out inside the European Agenda on Migration (Sept. 2015) as a step forward to bring together all relevant EU agencies like Frontex, EASO and Europol directly behind the border in an attempt to implement a strict screening and registration system as well as access to “international protection” seem to function. This implicates as well a fast track asylum procedure that only examines the “accessibility” of a claim as we have described in the beginning of our paper ; on the other hand, the Greek asylum appeal boards rejected the claim of the deal that Turkey is a “safe third country” and ordered that asylum applications by Syrian refugees on the islands have to be processed. The Greek state is already reacting and is trying to change the composition of these boards to make the deal work. Nevertheless, some refugees managed to get temporary papers and left to the mainland, whereas others did so by undocumented means; Furthermore, as volunteers at Lesbos told us, the numbers of arrivals already seem to have increased, especially in the wake of the failed military coup in Turkey, with boats nearly arriving daily.

Literature

Agamben, Giorgio (1998): Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life. California.

Baban/Ilcan/Rygiel (2015):

Fassin, Didier (2007): Humanitarianism as a Politics of Life. In: Public Culture 19(3): 499–520.

Kasparek, Bernd / Speer, Marc (2015): Of hope. Hungary and the long summer of migration.

Mountz, Alison (2011): The enforcement archipelago: Detention, haunting, and asylum on islands. Political Geography 30(3): 118-128.

Panagiotidis, Efthimia / Tsianos, Vassilis (2007): Denaturalizing “Camps”. Überwachen und Entschleunigen in der Schengener Ägäis-Zone. [Surveillance and Deceleration in the Schengen-Aegean Zone.] In: Transit Migration Forschungsgruppe (Ed.): Turbulente Ränder. Neue Perspektiven auf Migration an den Grenzen Europas. [Turbulent Margins. New Perspectives on Migration at the Borders of Europe.] Bielefeld, 57–85.

The views and opinions expressed in the articles published on HarekAct are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of all editorial board members.