Article by Nicolas Parent originally published for IN/WORDS MAGAZINE & PRESS

New York, 1927 – Edward Lasker and Aron Nimzowitsch, two of the greatest minds in chess at the time, went head to head in an off-hand game. At that time, smoking was almost synergetic with chess playing. Nimzowitsch, however, had a severe allergy to smoke and records show that he often requested tournament directors and ombudsmen to enforce a no smoking rule during game play. Lasker, on the other hand, was notorious for his strategy of ‘smoking out’ his opponents, typically burning cheap cigars with an unbearably foul scent. Before this specific match, Lasker agreed not to smoke whilst playing against Nimzowitsch. However, mid-game, Lasker pulled out a cigar and laid it on the table. Nimzowitsch furiously acalled upon the tournament director to intervene, but this was to no avail as Lasker had yet to light the cigar. Dissatisfied, Nimzowitsch responded by saying “(…) but he is threatening to smoke, and as an old player you must know that the threat is stronger than the execution” (Winter, 2015).

Albeit the comical exchange, a similar narrative has developed in respect to what European political circles and newspapers have called a ‘migration crisis’. In 2015, 850,000 migrants crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey and landed onto European soil via various Greek islands (Leadbeater, 2016), occurring predominantly during the summer months when weather was tempered and the sea was calm (UNHCR, undated). Specific reasons for this sudden surge in migration have not yet been identified through scholarly research, but most news agencies attribute the inflow to Germany’s suspension of the Dublin protocol and Chancellor Angela Merkel’s statement declaring an open door policy for Syrian refugees in late August (Abé et al., 2015; The Economist, 2015).

However, for those working in the field of human rights and migration in Turkey, this move towards Europe was not shocking.

Truth be told, it was only in 2014, after increasing pressure from the EU, that the Turkish Parliament finally enacted a legally- binding asylum policy providing certain rights to Syrian refugees (see Temporary Protection Regulation, 2014). That means that for three years, Syrian asylum seekers -referred to as “guests” by Turkish politicians – had no internationally recognised status and were thus in a legal limbo and at the mercy of charity. Effectively, “(…) the Turkish government [had] adopted a discourse of ‘generosity’ rather than one based on rights” (Oktav and Çelikasoy, 2015: 415). Whether Merkel or Turkey’s weak asylum policies are responsible for what the media has collectively named a ‘migration crisis’ in Europe, what is certain is that following the summer of last year, escalating tensions between European bodies led to negotiations with Turkey as a means to seal the borders and devise a containment strategy.

In the coming months, the EU would effectively sell itself out, trading off its legitimacy as a global institution for human rights and international law in exchange for measures to stop refugee inflow threatening so-called European identity.

The European Commission’s delayed release of their annual report on Turkey till after the November 1st Turkish elections was one of the first defining moments showing a willingness to forfeit integrity for control of migrant flows. The EC was concerned that “EU criticism of Ankara’s record would complicate negotiations on how Turkey could help Europe stem the flow of migrants into the continent” (Zalan, 2015), a decision that was later criticised by the European Parliament, stating that this was “(…) a wrong decision, as it gave the impression that the EU is willing to go silent on violations of fundamental rights in return for the Turkish Government’s cooperation on refugees” (European Parliament, 2016).

This willingness only became more apparent as the months passed by, with the most critical development occurring in February 2016. Greek authorities–supported by other EU member states such as France and Germany–declared Turkey a “safe third country” (Tsiliopoulos, 2016), explaining that they believed it met all five requirements set out in Article 38 of Directive 2013/32/EU. This decision, condemned by multiple international human rights groups, was a clear mockery of international law (Roman et al., 2016; Frelick, 2016). For instance, one requirement states that the country in question needs offer the possibility “(…) to request refugee status and, if found to be a refugee, to receive protection in accordance with the Geneva Convention” (European Parliament, 2013). However, as Turkey never amended its geographical limitation set out in the 1951 Geneva Convention – specifying ‘refugee’ as a forced migrant of European origin – it has absolutely no legal obligation to offer this possibility to Middle Eastern or North African migrants.

The EU also believed Turkey to be in conformity with the requirement stating that it must abide by the rules of non-refoulement – “expulsion or compulsory return to any State where he may be subjected to persecution” (Lauterpacht and Bethlehem, undated) – albeit multiple reports of forced returns (Amnesty International, 2015; 2016). Overlooking this evidence, and its serious illegality in respect to international law, however, was no big surprise given the substantial evidence documenting European authorities undertaking push back operations at sea (Booth et al., 2013; Alarmphone, 2016). Or, perhaps European authorities simply lacked a well-needed situational understanding of Turkey, explaining why they blatantly disregarded the fact that the peace process between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) had ended months ago (Akyol, 2015) and that Kurdish migrants from Syria and Iraq could effectively be at risk in Turkey. All of these observations begged the question “is Turkey really a safe country for migrants?” The EU sure thought so and now an agreement with Turkey to stop migrant flows across both land and sea borders could move forward.

On March 18, 2016, the EU-Turkey action plan was initiated (European Council, 2016). The readmission agreement set out in 2013 was expedited and Turkey would now work on strengthening its border security to stop migration toward Europe. As a means to further deter migrants from attaining Europe by informal means, the EU made a bold move by announcing that migrants having crossed over to the EU illegally would now be sent back to Turkey. Furthermore, the EU would reward those asylum seekers in Turkey that had not attempted to cross into Europe informally, granting asylum to a maximum of 72,000 hand-picked migrants currently living in Turkish refugee camps.

This was part of the ‘one in, one out’ agreement; a bargain on the cusp of what arguably resembles a form of human trafficking.

Turkey, in return, was promised 6 billion euro for humanitarian aid, development programs and the construction of state of the art repatriation and detention facilities in Turkey. Furthermore, the visa liberalisation process for the Schengen zone was activated and would be granted on condition that Turkey meet all 72 criteria set out by the EU. This entire deal, presently in its preliminary stages of implementation, was not drafted with extensive consultation of experts in international migration law and thus is largely ad hoc, shedding some light on what this deal really is: overt bribery where cash, visas and logistical resources are handed out in exchange for human lives.

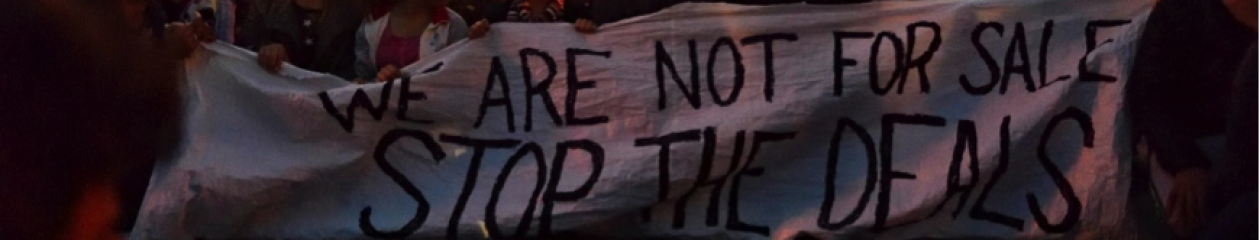

For months now, an armada of organisations have either heavily criticised this deal (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Médecins Sans Frontières, Council of Europe, Mülteci-Der, multiple Red Cross National Societies, and many more) or denounced that it may well be out of line in respects to international law (UNHCR, European United Left, Global Justice Now, etc.). However, at present time of writing, the summer months are approaching at lightning speed, and fearing another peak in migration from the Aegean Sea crossings, European big wigs are scrambling to seal the deal with Turkey.

It is quite clear that parallels exist between the Lasker-Nimzowitsch and EU-Turkey match ups. By the end of last summer, Turkey had laid down the cigar on the table, threatening that if lack of European support continued so too could migrant flows into the EU. As reports show, there has been an increase in far-right nationalism in Europe over the last few years (Adler, 2016); identity-protective perception has undoubtedly participated in packaging refugees as a terrifying threat. However, considering that even if all refugees in Turkey (currently quoted at 3 million) moved on to Europe, which is highly unlikely, the total population of Europe would only increase by 0.0000004%.

Who knows the extent of Nimzowitsch’ allergy–slight coughing, heart palpitations, risk of death–but, what is argued here is that the threat of refugees in Europe is much weaker than its potential execution. Debatably, the threat to the integrity of international migration law is far greater. For instance, with Kenya’s recent announcement that it wishes to close down Dadaab–the world’s largest refugee camp–the impacts of the EU- Turkey deal are evidently reverberating, with organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières imploring Kenya to reconsider: “Rather than endorsing the broken and inhumane policies of the EU and others, now—more than ever—is the time for Kenya to embrace and continue its tradition of providing refuge” (Lavelle, 2016). Just as Lasker laid down a cigar mid-game, developments are still to be seen on how this deal between Turkey and the EU will pan out. Let’s see which discourse–humanitarian or fascist–will prevail.

Nicolas Parent (2016): Refugees as Peons in Foreign Policy: Turkey, the EU and Reflections of Lasker and Nimzowitsch. Ottowa: In/Words Magazine & Press, Vol 15/ Issue 3, p. 99 – 104.

References

Abé, N., Amann, M., Gude, H., Müller, P., Neukirch, R., Pfister, R., Schmid, B., Schult, C., Stark, H. and Wiedmann-Schmidt, W. “Mother Angela: Merkel’s refugee policy divides Europe.” Spiegel.de. Der Spiegel, 21 Sept. 2015. Web. 23 Apr. 2016.

Adler, K. “Is Europe lurching to the far right?” BBC.com. British Broadcasting Corporation, 28 Apr. 2016. Web. 10 May 2016.

Akyol, M. “Who killed Turkey-PKK peace process?” Al-Monitor.com. Al-Monitor (Washington), 4 Aug. 2015. Web. 8 May 2016.

Alarmphone (2016) Moving On: One Year Alarmphone, WatchTheMed.

Amnesty International “Urgent Action: Refugees in Turkey risk expulsion to Syria.” Amnesty.org. Amnesty International, 20 Nov. 2015. Web. 3 May 2016.

Amnesty International “Turkey: Illegal mass returns of Syrian refugees expose fatal flaws in EU-Turkey deal.” Amnesty.org. Amnesty International, 1 Apr. 2016. Web. 23 Apr. 2016.

Booth, K., El Dardiry, S., Grant, L., Intrand, C., Kynsilehto, A., Mantanika, R., Martin, M., Rodier, C., Tassin, L. and Ottavy, E. (2013) Frontex between Greece and Turkey: At the border of denial, FIDH, Migreurop and EMHRN (joint publication).

European Council “EU-Turkey Statement, 18 March 2016.” Consilium.europa.eu. European Council, 18 Mar. 2016. Web. 4 May 2016.

European Parliament “Directive 2013/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection.” Eur-lex.europa.eu. European Parliament, 26 Jun. 2013. Web. 1 May 2016.

European Parliament “European Parliament resolution on the 2015 report on Turkey (2015/2898(RSP)).” Europarl.europa.eu. European Parliament, 5 Apr. 2015. Web. 7 May 2016.

Frelick, B. “Is Turkey Safe for Refugees?” HRW.org. Human Rights Watch, 22 Mar. 2016. Web. 12 May 2016.

Lavelle, K. “MSF urges Kenyan government to reconsider the closure of the Dadaab refugee camps.” MSF.ca. Médecins Sans Frontières, 16 May 2016. Web. 16 May 2016.

Lauterpacht, E. and Bethlehem, D. “The scope and content of the principle of non-refoulement: Opinion.” UNHCR.org. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, undated. Web. 3 May 2016.

Leadbeater, C. “Which Greek islands are affected by the refugee crisis?” Telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph, 3 Mar. 2016. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

Oktav, Ö. Z. and Çelikaksoy, A. (2015) “The Syrian refugee challenge and Turkey’s quest for normative power in the Middle East”, International Journal, 70 (3): 408-420.

Roman, E., Baird, T. and Radcliffe, T. “Analysis: Why Turkey is Not a “Safe Country”.” Statewatch.org. Statewatch, Feb. 2016. Web. 1 May 2016.

The Economist “Refugee realpolitik.” Economist.com. The Economist, 24 Oct. 2015. Web. 1 May 2016.

Tsiliopoulos, E. “Athens has designated Turkey a “safe third country”.” Newgreektv.com. New Greek, 11 Feb. 2016. Web. 25 Apr. 2016.

UNHCR “Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean.” Data.UNHCR.org. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, May 2016. Web. 5 May 2016.

Winter, E. “A Nimzowitsch Story.” Chesshistory.com. Chess History, 2015. Web. 25 Apr. 2016. Zalan, E. “EU publishes delayed report on Turkey’s sins.” EUobserver.com. EU Observer, 10 Nov. 2015. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.