By Umar Farooq

Turkish police conduced more than 1,400 raids across the country in a single week this November, with officials saying 6,890 people were detained for undocumented immigration, and 1,167 for suspicion of belonging to terror groups, either the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the Islamic State, or the Fetullah Terror Organization, which Ankara blames for an attempted coup in July 2016.

While more than 50,000 people have been charged with some crime related to that coup attempt since last year, little attention is given to what happens to thousands of those detained over suspected ties to the Islamic State, especially those who risk deportation back home to countries with a dismal human rights record.

Among the most vulnerable demographics is a diaspora from Central Asia. Hundreds of thousands of people from Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and ethnic Uyughurs from western China, have settled in Turkey. Many have left countries with some of the harshest restrictions on religious practices in the world . Uzbekistan for instance, has jailed at least 10,000 people for what human rights groups say are trumped up charges of religious extremism, and authorities have restricted the kinds of hijabs that can be worn, and barred minors from attending mosques. Others are coming to Turkey for a better life, leaving countries that have suffered from decades of corruption that has stagnated the economy. They are drawn to Turkey for cultural reasons – Turkish is similar to many Central Asian languages, and the region’s inhabitants follow the same school of Sunni Islam – as well as the fact that it is one of the few countries where they can obtain a visa on arrival. Immigrants from many Central Asian countries can obtain between a 30 day and 90 day tourism visa on arrival in Turkey, but many seem to settle here, and not all are able to meet the requirements needed to obtain proper residence permits, leaving them at risk of deportation.

For decades now, Turkish nationalist sentiment and sympathy for the plight of fellow “Turkic” peoples in Central Asia has meant authorities have turned a blind eye to undocumented migrants from the region, but this is changing, as Turkey turns away from the European Union and builds ties with Russia, China, and Central Asian governments. Those governments have tended to use the threat of terrorism to crackdown on political dissents. With Turkey seeking to deal with terror threats itself now, migrants are at risk of being deported over security concerns, and upon return to their home countries, these individuals are at risk of being labelled as extremists by those governments as well.

Turkey has been hit by dramatic terror attacks by the Islamic State, the most deadly of which have been blamed on suspects from Central Asia. The 2016 New Years Eve attack in Istanbul for instance, was allegedly perpetrated by a citizen of Uzbekistan. That attack sparked a weeks-long manhunt, and several instances of Central Asian-looking men being beaten by mobs on the street in Istanbul.

One police raid on 18 homes in Istanbul in 2015 resulted in the detention of some 50 ethnic Uzbeks and Tajiks, including 20 minors. Turkish media outlets reported the children were being trained to be fighters in basement seminaries by Islamic State. But weeks later, authorities released or deported all those detained, and no terror charges were brought against them. Media outlets never ran an update on the raid, in a pattern of misinformation that has repeated in police operations since then.

In September 2016, Turkish police detained Abdulkadir Yapcan, an aging ethnic Uyghur from Western China, who Beijing listed as one of its 11 most wanted terrorists in 2003. Most of the others on that list currently live exiled in Western countries and include journalists and well-known Uyghur political activists. Yapcan lived in Turkey for more than a decade as a celebrated political activist for the Uyghur minority, and the attempt by Turkish authorities to deport him in 2016 to Kazakhstan – thought to be a transit point for China – was met with protests in the country. A ruling by the European Court of Human Rights later prohibited Turkey from deporting Yapcan anywhere, out of concern he might be imprisoned and tortured eventually in China, but the fate of hundreds of other Central Asians wanted back home has not been so kind.

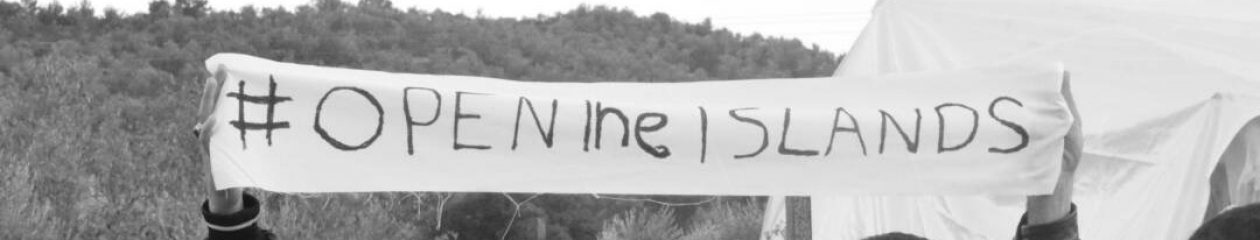

Turkish activists have been conducting online campaigns to halt such deportations, but have not always succeeded. This September, for instance, an activist in Istanbul received a voice message from an Uzbek woman asking for help. Her husband, detained months earlier, was being forced to board a flight along with seven other Uzbekistan nationals by Turkish police. He passed a note on a napkin to another passenger, with a simple message to call his wife and inform her. The Turkish activist desperately called contacts in the government, but with just 30 minutes left before takeoff, was unable to get the men off the plane. All the wife knows is that the men landed in Tashkent, based on information from another passenger, but they have not been seen or heard from again.

Turkish political leaders – from the left to the right – had long prided themselves on championing the cause of “Turkic” ethnicities in Central Asia, but given the challenge posed by the Islamic State, it appears that the tide may now be turning and thousands of migrants may be at risk of being forced back home, into the hands of governments who have a history of jailing and torturing political dissidents and alleged religious extremists.