Syrian Women’s multiple burden at the labour market and at home.

by Rejane Herwig

The living conditions of Syrians in Turkey are for a majority very poor and tend to have a negative effect on a psychological as well as a physical level. Looking at those through a gender lens renders visible that such circumstances often have even more severe effects on women.

In the scope of the research for my master thesis I worked with Syrian women living in Şanlıurfa on their experiences of violence and daily modes of resistance (Herwig 2017). Most of the women I spoke to said they were living in places that were acceptable but very different from the places they were living in back in Syria. Manon, one of them, explained that at the time of our meeting she was living with her family of seven in a one-room apartment without a bathroom due to the fact that they couldn’t afford a bigger and better-equipped place.

Living in such conditions is not an exception as the organisation MAZLUMDER explains in a 2014 report on Syrian Women Refugees. They point out that flats rented to Syrians especially in cities close to the Syrian border like Şanlıurfa are often far beyond humane conditions: very small, often without sanitary facilities and with high levels of moisture. Spaces like basements, storehouses or warehouses are rented as living spaces to Syrians, too. Of course, such places have serious qualitative and quantitative deficiencies in terms of basically required furniture and shelter, hygiene conditions, access to required energy resources for heating the home and water (cf. ibid). These situations were also portrayed in Turkish and in international media and became a common accepted knowledge, even in co-existence with notions of Syrians as privileged (Şimşek 2016; al-Shihab 2015; Söylemez 2014).

A lot of Syrian women in Şanlıurfa spend most of their time rather isolated in those unhealthy sheltering conditions. One of the reasons for this is the low employment rate, another one is their traditionally assigned place in the private sphere. An understanding of gender roles with clear positions for women as caretakers and men as bread winners and heads of the family are widespread among large parts of the Syrian as well as the Turkish society. In the case of Şanlıurfa, different influencing factors foster this condition. Generally, public spaces are rather male-dominated and the large majority of society is conservative. The male members of the family, either in their free time or even when they are unemployed, leave the house and spend time outside, while women often stay at home. (However, it became also clear during the meetings with my interlocutors that among the younger and well-educated generation those attributions become less and traditional gender roles were and are shifting due to the necessity to generate income.)

Having this situation in mind, the ambiguous approach of NGOs to “women’s empowerment” and possible pitfalls of a gendered (sex-specific) and one-fits-all approach bear the risk of once more reinforcing the idea of the home as a female and safe space. Ambiguous, because they on the one hand try to tackle the issue of gender-based violence and disadvantage of women, while on the other hand are themselves caught within an overall more traditional approach towards gender roles based on culture-based explanations and arguments. By this means, although it may be not intended, they also play their part in perpetuating traditional gender roles and unequal power relations. NGO approaches to educate women in professions like sewing or hairdressing, with the aim of enabling them to work from home, tend to worsen their often already difficult situation. Not only is the traditional assumption that women would be safe from violence, if they would just stay at home, very problematic. But moreover, not taking the living conditions they face into consideration is rather dangerous.

The conditions under which many female Syrian refugees live and the multiple intersecting discriminations they face in Turkey are severe. At the same time, several humanitarian aid organisations (in Şanlıurfa) are reaching out predominantly or exclusively to female refugees and children. Nevertheless, the support they receive is often gender-biased. This becomes evident when looking at what is offered in terms of training in traditional vocations like hairdressing or sewing. Although a lot of organisations set up the role of Gender-based Violence officers and have an outspoken objective to support women, the programs on offer tend to be based on traditional sex-specific roles. Due to that kind of conceptualisation, an opportunity for women to expand skills that are outside of traditional niches is missed.

On top of it, the trained professions are also such that women can easily do them at home. This, on the one hand, takes into consideration that women with children might not be able to work at all, if they cannot work from home. On the other hand, even if they are working, it again pushes them further back into the private sphere where they are more isolated from the public and makes sure that they shoulder both: unpaid care and waged work, and exposes them to possible health issues caused by unacceptable housing conditions.

“But the point is that we are not looking for providing jobs at home for females. We are aiming or as much as we can, to create a safe environment or safe jobs outside of our houses. It’s not possible to stay at home all the time if you are not safe.” (Tara, one of my interlocutors)

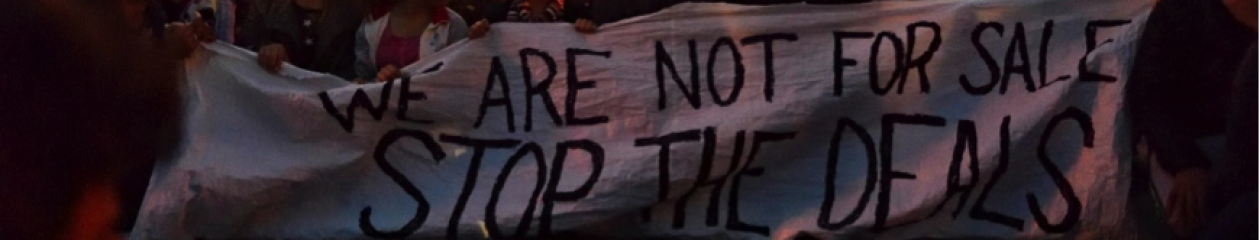

My interlocutors themselves pointed out these issues demanding change towards a safe environment at home and in the work place.

Even if they take up a job outside, the conditions in the textile sector are often intolerable. In Istanbul for example Syrian women often work in so called “Merdıvenaltı atölyeleri“ (unlicensed ateliers) where they are exposed to repression, discrimination and bad treatment (Bostancı 2017). In this kind of ateliers, which cannot be seen when passing by on the street as they are located in the rear of basements and in windowless rooms, women and girls from the age of 10 work 11 hours per day without sufficient breaks (ibid.)

My research as well as Bostancı’s article render visible that even Syrian women who are well educated, finished high school, attended or graduated from university, often fall through the cracks and take up this line of work as well, which is far from what they were educated for, and/or are not able to pick up on their studies. They are forced to do so by economic circumstances, sometimes being the “new and only bread winner” of the family. Manon, one of my interlocutors, expressed that she would love to go to university again. But as she is taking care of the whole family, she wouldn’t have the time to study properly and attend classes, not to mention the money to pay for a private university or to learn Turkish first. Nevertheless, most of the NGOs offer the same workshops to all women – a one-fits-all solution – educating them for gender-specific and badly paid jobs in which they can easily be exploited.

Why isn’t there a stronger orientation towards the women’s individual needs and skills: prepare them for better paid jobs on the official labour market in safe environments or to start or carry on their university education?

Literature

al-Shihab, Mosab (2015): Syrian Refugees Forced to Share Housing in Turkey. In: IWPR (eds.): GLOBAL VOICES. MIDDLE EAST. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/syrian-refugees-forced-share-housing-turkey.

Bostancı, Papatya (2017): “Çalışanı Meşgul Etmeyin”: Merdivenaltı Tekstil Atölyelerinde Mülteci Kadın Olmak. In: Biamag Cumartesi (eds.): Haber Listesi. https://m.bianet.org/biamag/kadin/190220-calisani-mesgul-etmeyin-merdivenalti-tekstil-atolyelerinde-multeci-kadin-olmak

Herwig, Rejane (2017): Victimisation and Resistance. Syrian Female Refugees in the Turkish City of Şanlıurfa.

Herwig, Rejane (2017): Strategies of Resistance of Syrian Female Refugees in Şanlıurfa. In: Movements 3(2) Turkey’s Changing Migration Regime and its Global and Regional Dynamics. http://movements-journal.org/issues/05.turkey/12.herwig–strategies-resistance-syrian-female-refugees.html.

Kadın Olmak. In: Biamag Cumartesi (eds.): Haber Listesi. https://m.bianet.org/biamag/kadin/190220-calisani-mesgul-etmeyin-merdivenalti-tekstil-atolyelerinde-multeci-kadin-olmak

MAZLUMDER, Women Studies Group (2014): The Report on Syrian Women Refugees.

Söylemez, Ayça (2014): Suriyeli Mülteciler Nasıl Yaşıyor? In: Bianet (eds.): Haber Listesi. https://bianet.org/bianet/insan-haklari/160662-suriyeli-multeciler-nasil-yasiyor.

Şimşek, Doğus (2016): Situation of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. In: bpb (eds.): Syrian Refugees in Turkey. http://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/laenderprofile/229982/syrian-refugees-in-turkey.