The New Arab published a story on February 2nd on IOM ‘voluntary return programme’: “A scheme to repatriate refugees whose asylum bids have been rejected amounts to bullying and bribing desperate people to return to desperate situations, reports Matt Broomfield.” Valeria Hänsel also wrote on that same issue for HarekAct two weeks back.

Via The New Arab – A “voluntary” returns programme being heavily marketed to refugees is leaving them stranded in inhumane conditions in Greek and Turkish jails for months at a time, and facing imprisonment and torture once they return to their home countries – if they are ever able to get there at all.

For many refugees arriving in Greece and Turkey, whose claims for asylum are rejected, the International Organisation for Migration‘s Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) programme is effectively the only alternative to brutal jail systems. They are forced to give up their right to appeal their asylum decision in order to escape six or 12 months of confinement by accepting “voluntary” return.

AVRR is “a more humane and dignified alternative to deportation”, an IOM spokesperson told The New Arab. “As a rule, migrants receive return counselling to ensure that they are able to make an informed decision in choosing [AVRR]… In that sense, IOM does not coerce, force or influence any individual to participate in the AVRR programme.”

But asylum seekers who have experienced the programme told The New Arab they were misled into accepting inhumane conditions, detention and torture, after joining a programme one lawyer called “a fist in a velvet glove… wrongful, coercive and distasteful”.

‘Voluntary’ deportations

The AVRR deal sounds simple: give up your asylum claim, or renounce your right to appeal, and you will be offered a small cash stipend of €500-€1000 ($620-$1240) and transferred by plane to your home country.

With 18-month waits for an asylum decision common, asylum offers rare, and conditions in military prisons-turned-refugee camps such as Moria on Lesvos at breaking point, it is unsurprising that many asylum seekers here opt for “voluntary return”.

Ethiopian Jeremiah describes his experience: “The police arrested me... After a while they [handcuffed] two of us together and put us on a ferry. We were all voluntary returns, but they treated us like robbers.”

It hardly sounds like a “voluntary” programme – and that’s because it isn’t, according to Lesvos-based lawyer Ariel Ricker of Advocates Abroad. “People don’t get full information, therefore there’s not full informed consent,” she tells The New Arab.

When the programme was introduced in May 2017, NGOs and legal organisations condemned it for limiting asylum seekers’ right to appeal and coercing people with solid asylum claims into returning back home.

Nearly five times as many refugees take AVRR as are forcibly deported from Greece – more than 9,000 across the eighteen months up to December 2017, according to IOM statistics. This is proof, according to IOM’s promotional materials, of the programme’s success. They have marketed the programme with everything from TV spots to branded powerbanks to frequent campaigns in the detention centres, refugee camps, and island hotspots.

Ricker says IOM officials themselves “are wonderful to work with, but the programme itself is flawed… Like all policies it comes down to racism, fear and money. We’re basically bribing them to go back.”

Limbo

Refugees who accept AVRR deportation are forced to sign a waiver, seen by The New Arab, stating “that in the event of personal injury or death during and/or after… participation in the IOM project, neither IOM, nor any other participating agency or government can in any way be held liable or responsible”.

Jeremiah was refused food and use of a bathroom, and mistakenly thrown into jail in Athens before friends lobbied IOM to track him down and transfer him to a pre-removal detention centre. Other refugees have been wrongly deported to Turkey even after signing for AVRR, and disappeared into the byzantine depths of the prison system there.

Hamid, an Iranian asylum seeker who worked as an interpreter for Advocates Abroad, was arrested while attempting to make his way irregularly to Italy. He feared reprisals on the Greek island of Samos, where police violence against refugees is well documented. And so he accepted the offer of “voluntary” return to Iran – despite knowing “the moment I get back the secret police will take me into investigation”.

He spent 66 days in four different prisons before finally being returned to Iran and the hands of the secret police. Plagued by bed-bugs and hunger pains, he made a suicide attempt while still detained in Greece. The IOM spokesperson said their organisation “does not and cannot interfere” with Greek legislation about the detention of migrants who arrived in Greece irregularly.

Refugees are typically detained in Athens anywhere between a week and several months while they wait for enough fellow nationals to arrive to fill a chartered flight back to their country of origin. Pakistani asylum seeker Junaid says he sat in detention in Athens for six months, “watching people go back to their country every day”, but unable to join them.

“Every time I cried for going back to my country,” he tells The New Arab.

“I don’t have the possibility to go forward to Athens or back to Pakistan. For refugees who don’t have a country… it is very bad”

More Pakistanis have been deported under AVRR than any other nationality – but Junaid says anywhere from 100 to 150 of his fellow nationals are currently trapped in detention in Athens, as the Pakistani government refuses to accept them for return.

He himself worked and lived legally in Italy for 11 years, but accidentally allowed his visa to lapse while on holiday back in Pakistan. Since then he’s been trying to get back to Italy to pick up his old life. This led him on the dangerous route to Lesvos, where he was trapped in the inhumane refugee processing centre at Moria for six months before his transfer to a cell in Athens.

Like many others, he was a victim of the false belief – still peddled by smugglers – that it would be simple to leave the island and travel onwards to Italy.

With a wife and young children to support, he decided to give up and return to Pakistan. But his parents were refugees themselves, crossing into Pakistan from Bangladesh. “I gave up my passport and all my documents, but the embassy did not give an answer that I am Pakistani,” he says. “I was surprised, because IOM accepted my passport.”

After half a year of detention, during which time his wife was forced to pull their children out from school back at home, Junaid was allowed to return to Lesvos to pick up his asylum claim – which was rejected. Farcically, he is now trapped: “I don’t have the possibility to go forward to Athens or back to Pakistan. For refugees who don’t have a country… it is very bad.”

In response, IOM said: “Programmes are based on indispensable cooperation with countries of origin that are involved, where needed, in the provision of relevant travel documents. As such, IOM Greece has no record of migrants returning through AVRR that have been denied re-entry to their home country.”

Junaid’s only option appears to be deportation to Turkey, likely spending many months in jail there and near-certain refusal of his asylum claim. At that point he can either come to Greece again and be rejected again, or smuggle himself back to Pakistan – where he is also being refused citizenship.

Bribes and violence

Refugees also experience detention or threats of arrests when they get off the plane in their home country – in practice, normally an excuse to extract a bribe. When the amount given to Pakistani returnees rose to €500, the amount courts started to demand in exchange for their freedom rose from around €80 to around €300 – an indication corrupt officials are following and benefiting from the IOM programme.

The better part of the reintegration money thus disappears into the pockets of the courts, while those who must send the money on to struggling families are left to face another few months in jail.

Others face harassment or worse, from government officials who may genuinely suspect them of sedition, or view the fact they fled their home country as anti-patriotic or shameful.

“They put a gun on my head, forced me in a car and brought me to an underground place. They took my papers, asked me endless questions, hit and tortured me. I stayed in this place for two weeks”

Jeremiah was an opposition political activist in his native Ethiopia, where the government ordered a state of emergency in October 2016 “that permits draconian restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly”, amid violent protests which saw hundreds killed and tens of thousands arrested.

He says he was only with his family back in Ethiopia for a few hours before he was seized: “Two men came with a pick-up to our place. They put a gun on my head, forced me in a car and brought me to an underground place. They took my papers, asked me endless questions, hit and tortured me. I stayed in this place for two weeks.”

He was told he was going to be executed, and wrote farewell messages to friends and family from his cell, before ultimately being released. He has since fled to a neighbouring country.

Returnees from Afghanistan, Iran and other nations also report facing a choice between detention and paying hefty bribes.

Again, IOM state they “cannot intervene” if a refugee such as Jeremiah faces “safety or security issues” after they are returned to their home country, but that they “have never received feedback of torture or abuse from any beneficiary upon return”.

Coercion

It beggars belief that anyone would return voluntarily into such circumstances. While Jeremiah was on Lesvos he received an offer to study at an American university. But he was trapped on the island, and unable to get to the embassy in Athens to secure the visa which was rightfully his.

“Voluntary” return was his last-ditch attempt to get to the embassy in Addis Ababa – and in the end, he was lucky to escape with his life.

Jeremiah’s story shows how people are coerced into accepting AVRR in a broader sense. When refugees are being confined to islands where human rights are being abused, they are often left with no choice but to return.

The IOM spokesperson noted that “structures on the islands were created for limited stay and are accommodating migrants for a prolonged period”, creating tensions which AVRR alone cannot alleviate.

Mahmoud, from Algeria, spent many months trying to leave Lesvos. When an attack by people smugglers left him hospitalised in a neck brace, he was visited by the police, and signed up for AVRR that day. He’s now saving money in Algeria to try and enter Europe by another route.

Likewise, under a new “fast-track” programme described as “racist and illegal”, refugees from so-called “undesirable” countries (such as Algeria) are being jailed upon arrival on the Greek islands, normally reached via the Turkish coast, before being put through a summary fast-track asylum procedure and returned to detention in Turkey.

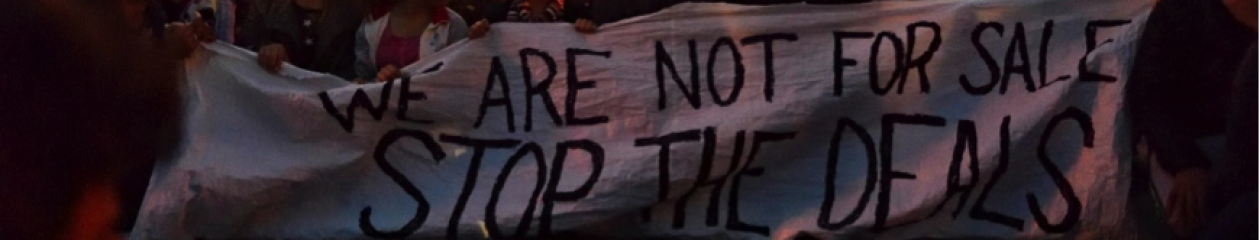

Knowing there will be no chance to escape the notorious Section B detention centre on Lesvos, many refugees therefore sign for “voluntary” deportation from within their cells. The “Moria 35” who were racially profiled, beaten and arbitrarily detained during political protests last summer were given the same option – wait 12 or 18 months in a Greek jail to face criminal proceedings, or sign up for AVRR.

Unsurprisingly, many signed up for deportation.

The threat of return to Turkey, in whose prisons human rights abuses are even more rampant than in Greece, is the biggest coercive factor of all. Refugees can expect six or 12 months detention, before a near-certain refusal: since the signing of the EU-Turkey deal, only two non-Syrians returned to Turkey have gone on to secure international protection.

While on Lesvos this reporter spoke to rejected asylum seekers who planned to pay smugglers to go back to Turkey, rather than risk detention by arriving through an official deportation programme. With people this desperate to avoid Turkish prisons, it is unsurprising many refugees sign away their legal rights “voluntarily” in order to escape the islands.

This article was originally published at The New Arab