Due to the reopening of the case of Festus Okey last week, Pelin Çakir summarizes and comments on the murder and its contexts for HarekAct

by Pelin Çakır

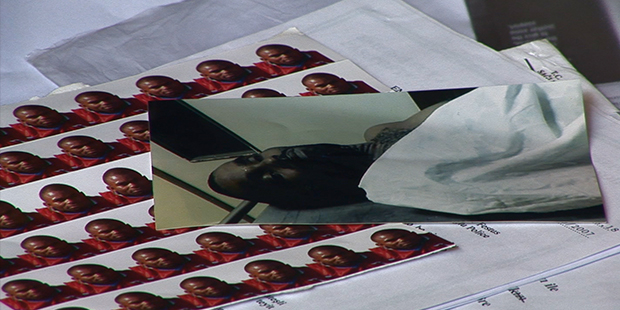

Festus Okey, was born in 1975, in the Abia state of Nigeria, one of eleven children born to a farming couple. His brother Tochukwu migrated to South Africa to support his family in their poverty, but told Festus that conditions were very bad there, leading Festus to come to Istanbul instead in 2005. He worked in temporary jobs and played football with amateur teams in the so-called African league of Istanbul, a league which gives hope to many African young men to be discovered by the agents of professional football teams and therefore become a reputed player. His friends were calling him Okute. By coincidence, he appeared in an independent documentary which reported on the league, firstly recorded while running in the field, then unexpectedly during his funeral (how his murder was initially acknowledged by the press).

It wasn’t easy to escape the police’s ‘attention’ as a black man in Istanbul. The first time he was arrested by police for being undocumented, and kept for several months in Kumkapı detention center until he managed to file an asylum application to the UNHCR. On the early evening of 20 August 2007, Festus Okey and his friend Mamina Oga were stopped by an undercover police officer in the central Beyoğlu area of Istanbul. The police officer later described how they were apprehended with the following words “black persons and citizens from the East draw more attention with respect to narcotics”.

Afterwards, they were brought separately to Beyoğlu Police station for interrogation. Okey was brought to the interview room (which is normally used for lawyer visits) while Oga was in the waiting room, when screams and a gunshot were heard. A short time afterwards, Okey was carried out of the police station by two police officers like a sack. Heavily injured, he was brought to a hospital in a police car, entering at 18:07. He lost his life there. The case was reported to the attorney general by 21:10, and the crime scene report was prepared by 01:10 by the same team who had caused his death. The report included the signature of the prime suspect in the shooting, the police officer Cengiz Yıldız.

Already before the first trial there were several pitfalls in the case. The human rights lawyers elaborated that these gaps could only be explained as an effort to cover-up the crime. The suspected police officer should have been detained instead of taking part in the initial investigation, and the case should have been immediately reported to the prosecution. Moreover, it was illogical that there were no residues of gunshot identified on the hands of the police officer who pulled the trigger (unless he had washed them away); there were no camera records found of the moment of the shooting while there were images showing the entry and exit of Okey (the detention room was said to be under construction, but this was denied by the lawyers working in the same area); the shirt Okey was wearing while entering the hospital was lost; and finally the suspicious police officer was not suspended from duty and even took back the same gun involved in the murder after a short period.

The police officer Yıldız was brought to the prosecution on the grounds of causing death by negligence, which normally carries a sentence of imprisonment from 4.5 to 9 years. His defense was centered around the allegation that Festus was involved in a drug offence (the same accusation which was narrated in the crime scene report), with even his counsel calling Festus a “drug dealer” during the hearing. Yıldız testified that they had found 13 packs of cocaine in Okey’s underwear, then when the other police officer left the room to inform the chief about the drugs found, Okey had tried to take his gun and eventually Yıldız pulled the trigger while trying to free the gun by stepping back. According to the forensic report, no alcohol or narcotic drugs were identified in Festus’ blood, and his shirt, the main determinant of the shooting distance and angle, was apparently lost in the hospital. Several of the next hearings were postponed due to a lack of confirmation about Festus Okey’s identity (as requested by the defence attorney). Turkish authorities were not able to solicit information from Nigeria for 4 years (they either sent the letter to the wrong authority or in the wrong language). By 2010, the activists of Migrant Solidarity Network (GDA) and human rights lawyers (115 individuals and some NGOs) demanded intervention in the case on the grounds of “moral hazard as citizens”, were respectively accused of “contempt of court” and were brought against the prosecution. Having gained contact with Okey’s family members in 2011, the lawyers requested the involvement of Festus’ brother, Tochukwu Gameliah Ogu, in the case, attempting to widen the investigation. But this attorneyship was refused because the brothers did not have the same surname (the official name Festus had on his Nigerian passport was Bethel Chinasaokwu Ogu, but he used the name Festus Okey, carrying his father’s name as surname). Following the 16th hearing on 13 December 2011, the police officer Yıldız was sentenced to 4 years and 20 days imprisonment. But one of the prosecutors objected to this decision on the grounds that the suspected police officer should have been condemned to 20 years of imprisonment for murder with eventual intent. The prosecutor argued that the police officer should understand the outcome of his misconducts (such as carrying his gun during interrogation, with the gunlock open); and that he had raised his gun with the aim “to interrogate Okey, scare him, threaten; for self-aggrandizement and display of power”. The Supreme Court overruled the lower court’s verdict, which dismissed Tochukwu’s application to intervene in the case, and stated that the court had not conducted a sufficient investigation. Okey’s case was reopened after 11 years with a new hearing dated 12 December 2018.[i]

The place of death: police station. The reason of death: racism

Eleven years since the shooting of Festus, a judicial deadlock has ensued, without any progress in illuminating the murder itself, and with various attempts to brush over the main details, as if to alleviate any expectations of justice. The case has turned into a symbolic one, and Festus Okey’s name has become familiar to many. It is recalled in song, in human rights reports, in a book, and it is still remembered today. He was a single black man in Istanbul, part of a community which is mainly ignored or marginalized by the host state and society, whose death could otherwise have easily been covered up, as the murderer no doubt expected. Despite this more than a hundred of people requested intervention in his case, and each of his hearings have been covered by the press.

The case became a symbolic one by bearing significance on two issues. Firstly, as a discrete case which was able to gather different groups in the hope of unveiling the perpetual and systematically obscured practice of police violence towards marginalized people. Secondly, by bringing attention to the racism and hatred directed at thus far overlooked migrants in Turkey. Following the lead of the Nigerian community who initially stood up in response to the murder, various other people and groups adopted the struggle of justice in the name of Festus Okey. The supporters in this struggle involved human rights organizations, lawyers, left/socialist parties, independent activists and members of new social movements such as ecologist or right-to-the-city groups, among others.

After the last hearing, I spoke with one of the longstanding followers of the case, an activist mainly engaged with the ecological movement, who elaborated the case similarly: “for me the most important thing about this case is that it brought together many rights-based groups, gave them an opportunity to question themselves and taught them to work together. I guess the fact that such a murder was blatantly committed in a police station and covered up, and there is the hope of revitalizing the case when it was almost closed, has probably created the feeling that we can still change something.” He explained that for him what matters most in this case is the course of its evolution, to which different groups have intervened and raised different problems, particularly today when racist sentiments are spreading from right to left. “The impetus to break this racism can appear by using this process here in the correct way, because at each hearing of this case there has been uproar, people have been able to keep thinking about something which they may never have thought concerning the migration issue.”

The same course of solidarity in practice paved the way for the formation of a network of activists concerned with the issue of migration, the Migrant Solidarity Network. The network made many efforts to publicize the case, spreading the initiative to individuals and human rights organizations to intervene, and following the case by trying to solve problems related to the procedure (such as obtaining the documents of identification). After their request of intervention was refused (and criminalized), the network considered the court decision in a press statement before the next trial as “a manifestation of the politics of discrimination and ignorance towards migrants”, and continued: “Festus Okey was a person living in this country. For us what matters is not the color of his skin, or whether he had citizenship status. He had the right to live wherever he wanted, as any other human being. Just like the 22-year-old Turkish migrant Hasan Gürz who was arrested by the police in Holland and died in the cell. It is not possible to close our eyes and ears to the dreadful discrimination sustained against migrants”

Murder and injustice: double bind for migrants?

The link that the Migrant Solidarity Network made was crucial in reminding us that the murder of Festus Okey is not a discrete case indeed. Today we can speak of a type of homicide particular to migrants, with large numbers of deaths caused systematically by the border regime as well as other mechanisms of marginalization and deprivation on the one hand, and sporadic deaths caused by violent attacks inspired by the vitriolic and ever-more blatant xenophobia and racism towards migrants on the other.

In Turkey, we know that migrant lives are under risk in several ways. Firstly, along the migration route, there are migrants who were murdered, or who froze to death after push-backs, and several unnamed have died while trying to cross the Aegean sea or due to deadly shootings at the Syrian border. A report produced by Health and Safety Labour Watch Turkey reveals that in 2017 alone, 88 immigrants died due to “work-related murders”, most of them Syrian. Several migrant women and LGBTI have been victims of sexual violence, murdered violently by men encouraged both by hatred and by the confidence of impunity. Some of those cases have been brought to the attention of the press, with two such murder cases recently resulting in the imprisonment of the defendants, achieved with the support of a feminist solidarity group who followed the trials. In 2016, the Turkish man who killed Jesca Nankabirwa was sentenced to 25 years in prison (after a reduction for ‘good conduct’), and this year, two Azerbaijani defendants were sentenced to lifetime for the murder of Violet Nanbata and sexual violence against her sister Beatrice (should we suspect that justice is erratic and it depends on who the defendant is?). A couple of the followers of the Festus Okey case who I spoke to on the day of the December trial referred to these two recent cases. They indicate that the practice of civilian pressure on the procedure of prosecution of violence against migrants, which started with the campaign around Festus Okey case, might have begun to yield positive outcomes in the demand for justice.

Yet sometimes those responsible for these deaths still remain resilient to the mechanisms of installing truth and justice. A Cameroonian women, Amina Tau Cady died due to inhumane conditions under detention, having been kept in an isolation cell, along with her newborn baby, in Izmir Detention Center on the pretext of “carrying the HIV virus”. Although the activists named it “not sickness, but murder”, her death did not lead to an investigation or sanctions on the responsible institutions. Another suspicious death under detention has been linked to the Festus Okey case owing to the similarities in the investigation procedure. 17 year old Afghan Lütfullah Tacik lost his life after being beaten by police in Van detention center. Afterwards, again, the cameras were broken, the defendant returned to duty, and there has still been no progress after human rights lawyers sought intervention in the case. As migrants are increasingly confined to out-of-sight areas and institutions, no doubt that many other unnamed murders happened. Festus was not the first, nor will he be the last, particularly if we consider the larger context, which the Justice for Festus Okey Initiative underlined at the trial last Wednesday:

“Because as justice keep a blind eye towards migrants, we have lost many others after Oury Jalloh in Germany, Adama Traore in France, and Festus Okey in Turkey; Darius Witek was beaten in Kumkapi detention center, Lutfullah Tacik in the foreign office of Van police station; Wisam Sankari and Roman were stabbed with hatred. Lately at the cases of Jesca Nankabirwa and Violet Nanbata, the murderers were convicted after a stubborn justice battle.”

Besides gender, there is also the race aspect in these murders, reflected in the “black lives matter” banners carried by activists at the last trial. A journalist who contacted Festus’ mother Love Ogu, quotes her words after adding that in the first half of the same year Festus was killed alone, four other Nigerians died as a result of police violence, because she says “This shall give me the opportunity to speak to other Nigerian mothers who lost their kids far away. Today my son dies, tomorrow another mother mourns for her child. If we stay together, we can prevent another Nigerian from dying. If my son could achieve, he would be a good football player and maybe Nigeria would have been proud of him.”

After 11 years: 12 December 2018

Finally we are together at the courthouse to attend the hearing, hopeful about the reopening of the case. There are followers from the initial group of intervening people, as well as new activists from recently emerging anti-racist groups, the director who recorded the image of Festus, the press, and human right defenders, altogether we form the Justice for Festus Okey Initiative. It is a regular morning in the courthouse, passerby students involved in the Bogazici University case wish us the best, an ‘Academic for Peace’ wants to join us before his own hearing starts, members of Human Rights Association appear to denunciate another racism issue and some of us will head on to similar cases afterwards. We were not allowed to enter the courtroom, despite the lawyers insisting on entrance to the board, arguing that there is an attempt to conceal this murder. The board refused for security reasons, since ironically during a recent trial of ex-police officers accused of being involved with FETO, the defendant party (officers) had attacked the court board.

After the trial, the lawyers described the attitude of the court as being positive, since this time the board had taken their demands into consideration. An interim decision had ruled to invite Festus’ brother to travel to Turkey and take a blood-DNA test in order to determine the identity, and moreover to allow the intervention request of Festus’ mother, therefore the documents from Nigeria and South Africa will be taken into consideration. In terms of the gains in the trial, the lawyers highlighted that “the decision of the Supreme Court Assembly of Criminal Chambers is very important in terms of defending the intervention to the case from the side of those ‘affected by the crime’. It is a crucial murder that risks our social security, and thus we wanted it to be investigated in detail. So we requested the investigation file in which Festus Okey was mainly criminalized and data that raise serious doubts were involved. We made a request to uncover the conspiracy set up by the Istanbul Police and the court accepted that as well.”

The next hearing date has been scheduled to take place on 2 April 2019. The followers released a press statement:

“The Festus Okey case has been one to bring the migrant communities and solidarity groups together for the first time, and to highlight the most basic claim for millions today: Black, Afghan, Syrian, Uzbek, women, LGBTI or men, all migrants have the right to a life in dignity and together we will keep standing against those who intend to our lives and asking for justice.

That’s why we are still following, we won’t forget, we will keep following until the discriminating practices, racism and hatred ends.”

So we will keep following.

So long Okute, I don’t know whether the roads of migration are longer and more intricate, or the roads to justice; but I know that we shall keep walking together…

[i] This whole procedure has been narrated with information gathered from İsmail Saymaz, “Polisin Eline Düşünce Sıfır Tolerans”, İletişim: 2012. IHOP “Festus Okey Gözlem Raporu”, 2011 (available online in Turkish), and bianet cover