“The last thing we lose is hope and as a saying goes: those who persevere, triumph”

Robin, Istanbul; November 2019

* Spanish version below / versión en español abajo

by Gianmaria Lenti (Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City, Mexico) & Bernardo López Marín (La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia)

This anthropological study focuses on the experiences and realities of Latin American migrants who are stuck in Turkey in irregular situation. They represent a large, but virtually invisible population due to their absence in official statistics and migration studies, although their arrival to the country is not a new trend. The majority of them have had their rights undermined and are exposed to abuse, difficulties and deprivation as a result of their irregular immigration status. Some of them find it hard to get jobs or, become the cheap labor that underpins the capitalist system of labor exploitation. Many Latin Americans migrants refrain from seeking help from the humanitarian system, since many of them do not know their rights, only speak Spanish, come from disadvantaged social strata or never achieved a higher educational level. Moreover, many humanitarian organizations deny them access to certain services for fear of reprisals from the authorities as a result of their irregular status.

The ethnography presented herein focuses on stories of Latin American people who came to Istanbul following a dream, but who got stuck in Turkey with few avenues to either reach Europe or return to their home countries. The people identified here are citizens of the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Bolivia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Colombia and Paraguay. Among them are Dominican women who have been forced into sex work to survive, Latin American men who live in poverty and overcrowded spaces, as well as those people who remained stuck in Turkey after leaving prison. In this context, we decided to avoid using the interviewees real names or any information that could compromise their identities, security and wellbeing. During the fieldwork conducted in 2019, we got in touch with members of the Latin American community who are currently stranded in Istanbul. Acquiring a better understanding of their life conditions as irregularized migrants in Turkey required close and extensive contact with the environment in which they pursue their everyday lives. As a methodological strategy, we decided to move in with four irregular migrants who were sharing a small and degraded flat in a working-class neighborhood of central Istanbul. Living conditions in our shared flat were extremely precarious, although this research strategy gave us the opportunity to consolidate strong relations of trust with our roommates and opened the doors to share their everyday life, preoccupations and concerns, while learning from their past life stories. In addition, they introduced us to their personal networks of friends and acquaintances in the city, especially in the neighborhoods of Dolapdere, Tarlabaşı and Kumkapı. The meetings and visits to Latin American people’s private abodes facilitated the approaching to a variety of Latin American migrants from different countries and social backgrounds. Lingering around the above-mentioned neighborhoods was challenging, due to the fact that police officers constantly assumed that we were Syrians and stopped us at least once a day to check on our visas and IDs. We were often aggressively body-frisked for drugs and questioned upon the reasons why we were walking around an area predominantly inhabited by underprivileged migrants and locals.

Trapped within an Arbitrary System

The majority of people we spoke to report having arrived in Istanbul after a friend or relative sold them the dream of a better life in either Europe or Turkey. Most of them had only been able to come to Turkey through making many sacrifices by receiving financial help from family and friends, accumulating debts or selling their assets. Many had their European visas denied and then came to Turkey because they were able to enter the country without a visa or due to the uncomplicatedness to obtain one. Some of them tried to enter Europe irregularly after spending some time in Turkey but found it complicated, dangerous and expensive, compelling many of them to try to return to Latin America, although without success. Arrival to Turkey via Europe was hassle-free since they were able to show their return tickets, but when they attempted to return via the same route, the Turkish authorities did not allow it, arguing that a transit visa for international connections in Schengen airports was compulsory. In accordance with the requirements of Schengen transit visas, almost all Latin American nationalities can transit visa-free through Schengen airports. The exemption is Dominican passport holders, who have connecting flights in France and Belgium. However, some Latin American citizens were hindered from returning to their countries by Turkish officials, suggesting a possible administrative negligence enacted by local Turkish authorities. Presumably, they overlooked the specific rules of transit visas for Latin American citizens and took arbitrary decisions, suggesting they were unsure about whether these travelers were permitted to transit freely through European airports or not.

Marcos’ testimony illuminates the reality of those who were unable to board their flights owing to these arbitrary decisions. Simultaneously, these people also have limited possibilities to remain legally in Turkey by extending their visas or regularizing themselves in the country. However, when their visas expire, Turkish authorities are unwilling to deport them to their own countries, due to the economic burden incurred by the Turkish State for long-haul travel.

“We tried to leave the country because our visas were about to expire. (…) We arrived at the airport and were hindered from leaving, as we didn’t have a transit visa to change flights, where we previously transferred. I flew from Punta Cana to Frankfurt, I transited through and I was given a hassle-free pass, so I arrived from Frankfurt to Istanbul without a visa or anything. (…) When we tried to return to the Dominican Republic using the same route, the Turkish authorities prohibited us from leaving, due to the lack of transit visas. (…) The second time, we came with everything ready and we were stopped again, the third time the same thing happened. It was by then when we gave up. We had no money, no place to live, nor anything else, so we supported ourselves by the small money our relatives could send us for food. They sent us a thousand Dominican pesos, which is the equivalent to one hundred liras, and we struggled to support ourselves with that. It was so hard that we even had to sleep three times in a park.”

Marcos, Istanbul; November 2019

Several Latin American migrants report that these circumstances have led them to become stranded in Turkey, without either legal permission or the money to return to their countries.

Exposure to the informal labor market

Employment is difficult to find, as many employers do not hire people without legal permission to stay, a reality that pushes migrants to live in hardship and precariousness. Latin American migrants tend to share small apartments or rooms, where eight to ten people live crammed together, while lacking the financial means to support their basic needs. A handful of migrants have jobs in textile factories or hotels, work between 12 and 14 hours daily and earn salaries oscillating between 1,200 and 1,800TL per month (€160 – 270), which is insufficient to cover their basic needs.

Mauricio is a Bolivian migrant who works in a suits and smokings factory because, according to his testimony, he is unable to find a better job.

“We work in a textile factory from Monday to Saturday from eight in the morning to ten in the evening. (…) The Turkish workers denigrate us, the boss treats us like animals and constantly shouts ‘çabuk! çabuk!’ (faster! faster!) at us. They don’t allow us even to sit for a second, much less to talk to each other while we work (…) We have half an hour for lunch and a similar break for dinner, but the food is not fresh, they keep it from previous days. Imagine, they’ve even given us stale food to eat.”

Mauricio, Istanbul; November 2019

Salary differences differ based on gender, with women receiving up to 25 percent less for performing similar working tasks. In addition, several migrants state that it was necessity that pushed them to accept such working conditions, being described as worse than in their own countries.

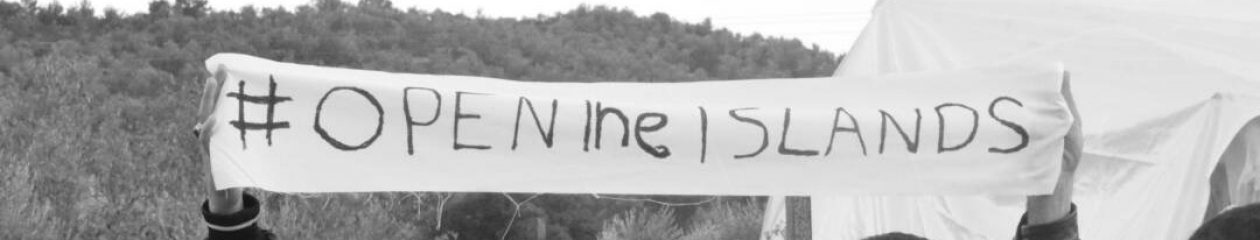

Push-backs at the Greek-Turkish border

Several Latin American migrants tried to reach Greece in the hope of enhancing their life conditions or to continue their journeys toward another European country. They hired facilitators who charged between €700 and 2,500 in 2019, depending on the crossing. These migrants report being apprehended right after crossing the Turkish-Greek border by black-hooded Hellenic paramilitaries who violently returned them to Turkey. They were never given the chance to apply for asylum in Greece, and thus the EU, received verbal abuse and were brutally kicked and beaten with large wooden sticks. Once back in Turkey, they became victims of the Turkish police who also abused and maltreated them.

Andy, a Dominican who tried to cross the Greek border near Edirne, reflects on the terror and suffering experienced by migrants during these crossings. His account is taken from a public denouncement which was written and sent by him to the United Nations, in the hope to be heard and also to inform the world about his experiences and those of his fellow migrants at the border:

“Serious things are happening at Greek border towns, people are even dying, as a result of what is happening to them in that territory, and it hurts to see families and babies battered by the Greeks. It is an emergency, there should be an intervention to protect immigrants, they are being tortured worse than slaves and in front of their relatives. (…) Nobody leaves their country by pleasure, but because of how much they suffer. They are being tortured there and then they are taken back at night (…) without distinction and without investigating the reasons they had to emigrate. (…) They mistreat them without compassion. Please, we are human beings, not animals, for the sake of God, don’t allow it, because many are dying in the crossing, due to the beatings they receive. Please, stop the Greeks, (…) send infiltrators and investigate, do not let them continue maltreating immigrants.”

Andy, Edirne; October 2019

Andy’s public denouncement reveals a facet of structural violence that unveil the reality experienced by many migrants when they cross the border without permission, while the European governments turn a blind eye to it, despite having knowledge of human rights violations perpetrated by Greek paramilitaries. These forced returns or push-back practices violate international laws and excludes migrant candidates for asylum, as stipulated in the 1951 Geneva Convention, while overlooking the fact that Turkey does not even provide migrants with this option, unless they come from European countries. In order to complement the previous postulate, Andy emphasizes:

“I would like to see lawmakers impersonating migrants, going there and crossing the border like we do, so that they could feel what we feel and get mistreated just the same way we get mistreated. Then, they could convince themselves that we are not making up stories and realize that this is a reality that migrants experience, so that the world can see how much we suffer.”

Andy, Istanbul; November 2019

Andy’s comment displays the frustration and anger that such mistreatment instills in migrants, while suggesting that the consummation of this ‘exemplary deterrent punishment’ is intended to reprimand and inflict terror, which aim to prevent them from returning to border areas.

Sex work as a mean of survival

We will now turn to the case of Latin American women who engage in sex work as one of the only options available for many of them to support themselves. Many were trafficked, deceived and brought to Turkey with the promise of getting jobs, since the local living standards were allegedly higher than in Latin America. Others hoped to get to Europe via Turkey and a handful were even told that Turkey was already part of the EU. Nowadays, they must negotiate their salaries with clients, ranging between 60 and 120TL (€10-20) for sexual intercourse or between 250 and 500TL (€38-75) for all-night accompaniment. These Latin American women usually look for their customers in the street, discotheques or bars, and avoid working in private homes, as they feel safer working in hotels. Most of them prefer fellow Latin Americans or African clients, as they underline that Turkish men treat them badly and can be very violent. Sometimes, clients do not want to go to hotels, nor do they want to pay, they demand to have unprotected intercourses, or even hit women when they do not fulfill their wishes. Some clients abuse alcohol and drugs, jeopardizing women’s integrity, especially when they become aggressive and violent. Rocio is a Dominican woman on her early 30s, who left her studies in Philosophy under the promise of a good employment in Turkey, through which she could help her relatives financially. Her close family members are elderly farmers who live on very low incomes. After arriving in Turkey, she found out that there was no employment position waiting for her, which compelled her to engage in sex work for the first time in her life, as the only option available to pay her rental expenses and cover her basic needs:

“Here in Turkey, I had to throw myself to the streets. (…) On one occasion, when I was working with a Turkish client, he locked me in his house and broke my phone chip so that I couldn’t communicate with anyone. Then, he threatened me and took away the money he had paid me because I didn’t want to engage in everything he wanted. The man wouldn’t finish and I couldn’t withstand it anymore, I was exhausted (…) My biggest fear was that he would rape me without a condom, or that he would hit me or that he was unhealthy, also because he was drunk and drugged. (…) Since I no longer wanted to be with him, he became violent, pushed me naked out of his house and threw my clothes out. I had to get dressed on the staircase. I left crying, tried to find a taxi and didn’t know where to go. (…) Life is not easy here. I would not wish for even my worst enemy to come to this country.”

Rocio, Istanbul; November 2019

Evidently, these power relations involve danger for these sex workers, especially when they are in the hands of men who mistreat them and threaten to report them to the police, leaving them vulnerable and helpless. In addition, this kind of work exposes them to serious psychological damage and places their physical health at risk, since they must always be cautious that clients do not break or remove condoms, leaving them unprotected from disease or pregnancies. In addition, they face difficulties in accessing the public health system, since their immigration status limits their access to medical care.

Several interviewees referred to the story of Carmela, a young Latin American sex worker who contracted HIV, and was denied access to treatment, due to her irregular status in Turkey. Antiretroviral medications and HIV monitoring are expensive and treatment is not provided to people without a residence permit or international protection status in Turkey. As a result, Carmela’s health worsened. Her desperate circle of friends and family collected money in an attempt to bring her back to her country to receive treatment, but Carmela’s consulate refused to help covering transportation costs and the person who booked the flights scammed her relatives by using a false credit card and forging the reservation. When her best friend accompanied Carmela to the airport, she was unable to board the flight because the payment was unconfirmed, leaving Carmela stranded in Turkey. Shortly afterwards Carmela died due to complications emerging from the disease. The authorities brought her body to a mountain on the outskirts of Istanbul, put her in a black trash bag and inhumed her on a mass grave, without giving her a funeral.

Brenda is a young Dominican woman who was forced into the sex work market by the person who brought her to Turkey after she paid €3,500 for the trip, which included the promise of arriving to Spain from Turkey. After narrating the story of Carmela, Brenda summed up her deepest fears with tears running down her face, while she stared into the void.

“I don’t want to experience the same thing that happened to Carmela, being thrown like a dog in a mass grave into a black bag. I also don’t want to be stabbed one day, bleeding and left alone, without seeing my country and my family again before I die. These are the biggest fears I experience here.”

Brenda, Istanbul; November 2019)

This heartbreaking story has marked the collective memory of Latin American migrants in Istanbul. Several migrants told this sorrowful account with sadness and despair, remitting to the fear they feel of dying in distant lands, without the possibility of returning to their countries and reunifying with their parents and children.

Imprisonment and life rupture

Another case highlights the plight of former convicts who became stranded in Turkey and now have little chance of returning to their countries. This section will narrate the story of Lina and Toño, as an epitomal example of the realities experienced by numerous Latin American migrants. They are a couple from Paraguay and Venezuela aged 48 and 39 who did not have the dream of traveling to Europe and earning euros, but became irregular migrants due to unexpected circumstances. Toño is from Caracas and comes from a family who struggle financially, while Tina was abandoned by her mother and grew up with her single father who was a musician and worked in the military. They both come from working-class families and had substantial debts in their home countries, facing the pressures of creditors and the necessity to support their children and parents. Lina and Toño left South America for Turkey due to the menaces of their creditors who were urgently demanding to have their money back. Simultaneously, the creditors offered the possibility to pay their debts by transporting a drug package within their bodies. Such a deal would allegedly have freed Lina and Toño from their debts, while also enhancing stability for themselves and their beloved ones. Regrettably, they were not aware of the potential consequences that could arise if anything went wrong. Upon arrival in Istanbul, they were arrested and sentenced to 8 and 12 years in prison for drug-trafficking, terrorism and attempt of murder. They were imprisoned in high-security prisons, suffered denigrating conditions and the erasure of their existence and family nuclei. Lina completed her eight-year sentence, but after leaving jail had no access to a residence permit or migratory regularization, and she is now without travel documents that would enable her to leave Turkey. She was arrested along with her six-month-old baby, who became ill with childhood leukemia during the time she accompanied her in prison. When her daughter was aged six, the Turkish authorities separated them and sent her to an education and care institution. She is now eleven years old, does not speak Spanish, has been converted to Islam and is only allowed to visit her mother for eight hours every third week. Lina misses her intensely, feels lonely and only wants to be a mother like any other, with her daughter’s closeness making her happy or her misbehavior angry. Lina’s countenance reflects her nostalgia for her daughter and the extent of the suffering arising from her absence. Together with Toño, she hopes to save money to emigrate to Spain and reunite with her sister who is waiting for them there.

Lina manifests her sadness when she underlines that she cannot take her daughter away from Turkey by legal means, since the Turkish authorities are keeping her with the argument that Lina can neither support her, nor possesses the financial means to cover repatriation expenses for both of them. She is unable to come back to Paraguay because her ex-partner has threatened to take their daughter away from her and even kill Lina, if she dares to return. She is trying to raise money to leave Turkey instead, while fearing the boat that could bring them to the Greek islands, as her greatest concern is her daughter’s safety. Meanwhile, she has told Toño that, in the case of shipwreck, he should let her drown in the sea and rescue the girl, who she considers to be the flower of life who deserves the dignified existence that Lina had never been able to give her. Lina has manifested her happiness when she perceives that Toño truly loves her daughter, even though he is not her biological father. Unfortunately, Lina can no longer work due to the presence of tumors in her body and is unable to pay for her operation, since her irregular situation prevents her from accessing the free social security scheme.

“I feel very sad, my life is finished and I want to go far, but I can’t leave my girl here. (…) I’m alone, as I’ve always been, but I’m now done, fucked by life and depressed (…) I don’t know what I’m going to do about my life, because we’re without money (…) I feel like I’m dead in life, I want to get away from everybody and live alone. (…) I no longer expect anything from life, everything has been pure suffering with only a few minutes of joy. I think I wasn’t born to be happy. (…) Now I’m dying of pain and sadness, (…) I no longer want anything from life because nobody awaits me, only my little daughter who is in an orphanage. For her, I will always be there until my last days, but I no longer want to live in these conditions.”

Lina, Istanbul, October 2019

The little money Lina and Toño managed to save has been spent on medical studies and painkillers which mitigate the severe pain afflicting her. She is desperate and has fallen into depression, all of which has made her health worse. While crying bitterly, her words reflect despair and suffering, bringing to the surface the effects that migratory irregularization produces on migrants. All they want to do is to leave a country in which they no longer want to be. However, they are being prevented from doing so.

Conclusion

Life conditions for Latin American migrants in Turkey are harsh, they are frequently victims of discrimination, xenophobia and social violence, merely because they are foreigners. Their life paths brought them to unexpected and sorrowful realities that keep them trapped in Turkey with few avenues to exit the country. Notwithstanding, they all hope to reconstruct their lives, greet their friends, eat their typical dishes, dance salsa and visit family members unseen for years. The stories presented herein are only a few examples of the invisible limbo in which many Latin American migrants are stuck in Turkey. While in theory, migration can be seen as a struggle for a more promising life, the case of Turkey shows that these perceptions, rather than being a palpable reality, represent only an increasingly distant utopia.

Invisibles y atorados en un limbo: Una etnografía del caso de los migrantes latinoamericanos irregulares en Turquía

“Lo último que perdemos es la esperanza y como dice un refrán: el que persevera, triunfa.”

Robin, Estambul; Noviembre 2019

El presente estudio antropológico se enfoca en las experiencias y realidades experimentadas por algunos migrantes irregulares de origen latinoamericano quienes se encuentran actualmente atorados en Turquía. Estos migrantes representan una población numerosa, aunque virtualmente invisible, debido a su ausencia en estadísticas oficiales y estudios al respecto del tema, a pesar de que su llegada a Turquía no representa una tendencia nueva. La mayoría carece de derechos y se encuentran expuestos a abusos, dificultades y privaciones a causa de su situación migratoria, se les dificulta conseguir empleos o se convierten en mano de obra barata que subyace al sistema de explotación laboral capitalista. Muchos latinoamericanos no buscan ayuda del sistema humanitario porque no conocen sus derechos, son monolingües, provienen de familias pobres y su nivel educativo suele ser bajo. Su condición irregular provoca también que algunas organizaciones humanitarias les nieguen ciertos servicios, por temor a represalias de las autoridades.

Este estudio se enfocará en relatos de latinoamericanos que vinieron a Estambul siguiendo un sueño o huyendo de una pesadilla, pero quedaron atorados y con pocas avenidas para llegar a Europa o regresar a sus países. Las personas identificadas provienen de República Dominicana, Cuba, Bolivia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Perú, Colombia y Paraguay. Entre ellos, se encuentran mujeres dominicanas que durante su estancia en Turquía se vieron empujadas al trabajo sexual para sobrevivir, aquellos que viven hacinados y en pobreza o latinoamericanos que quedaron estancados en Turquía después de abandonar prisión. Dentro de este marco, se decidió utilizar seudónimos y evitar difundir cualquier información que pudiera comprometer la identidad, seguridad e integridad de los participantes. Durante el trabajo de campo realizado en 2019, entramos en contacto con migrantes de origen latinoamericano que residían en Estambul. La intención principal de esta investigación recayó en la búsqueda de datos que permitieran alcanzar una mejor comprensión de la cotidianidad y condiciones de vida de estos migrantes irregulares en Turquía. La realización del trabajo etnográfico requirió mantener contacto cercano y extenso en las esferas donde se desarrollan sus vidas cotidianas. Se utilizó como metodología la observación participante y la realización de entrevistas, por lo que nos mudamos al apartamento que cuatro migrantes irregulares compartían en un barrio de clase trabajadora adyacente el centro de Estambul. Las condiciones de vida en aquel apartamento eran evidentemente precarias y fue necesario acomodarse a dichas circunstancias, aunque esta estrategia de investigación dio pie a la consolidación de fuertes relaciones de confianza con nuestros compañeros de departamento. Esta estrategia metodológica nos permitió adentrarnos en detalle a aquellos contextos que definen susvisiones del futuro y preocupaciones, mediante la memoria, sus relatos e historias de vida. Estos latinoamericanos nos introdujeron a sus redes de amigos y conocidos en los barrios de Dolapdere, Tarlabaşı y Kumkapı, facilitando el acercamiento a una diversidad de migrantes latinoamericanos de diferentes países y entornos sociales, quienes nos permitieron organizar las reuniones y visitar sus residencias privadas. Desplazarse en los barrios mencionados constituyó un desafío, debido a que los agentes de policía solían identificarnos como sirios y nos detuvieron al menos una vez al día para precisar documentos y verificar visas. En muchas ocasiones hasta buscaron drogas en nuestros bolsillos y mochilas con lujo de maltrato, mientras intentaban interrogarnos acerca de las razones que teníamos de caminar por áreas predominantemente habitadas por inmigrantes y ciudadanos desfavorecidos.

Atrapados dentro de un sistema arbitrario

Varios de los migrantes que conocimos relatan que llegaron a Estambul porque algún amigo o familiar les vendió el sueño de una vida mejor en Europa o en Turquía. Todos salieron de sus países con muchos sacrificios, acumulando deudas, vendiendo sus bienes y hasta recibiendo ayuda económica de familiares y amigos. Varios de ellos solicitaron visa europea, pero les fue negada, razón por la cual vinieron hasta Turquía con boletos aéreos de ida y vuelta, toda vez que podían entrar sin visa o era fácilmente obtenible. Algunos intentaron llegar a Europa de manera irregular, encontrando muchas dificultades y peligros para conseguirlo, por lo que intentaron volver a Latinoamérica, pero no les fue posible. Llegaron hasta Turquía vía Europa mostrando el boleto de regreso, pero al intentar volver por las mismas rutas, las autoridades turcas no se los permitió, argumentando que precisaban una visa de tránsito para tomar el vuelo de conexión. De conformidad con los requerimientos de esta visa, casi todos los latinoamericanos están exentos de obtenerla para transitar a través de los aeropuertos Schengen, salvo los dominicanos que pasen por Francia y Bélgica. A varios de estos latinoamericanos no fue permitido regresar a sus países, debido a que perdieron sus vuelos de regreso. Esta situación sugiere una posible negligencia administrativa por parte de las autoridades turcas, quienes presumiblemente desconocen los detalles de las reglas de excepción de visas para ciudadanos latinoamericanos y toman decisiones arbitrarias, sin asegurarse de las restricciones de tránsito por aeropuertos europeos de acuerdo a nacionalidades específicas.

El testimonio de Marcos ilumina la realidad de aquellos latinoamericanos que no pudieron abordar sus vuelos. Recordemos que las autoridades turcas no deportan ciudadanos de países lejanos por el alto costo que incurre al Estado, aunado a que las posibilidades de extensión de visas o regularización migratoria son limitadas.

“Intentamos salir del país porque se nos vencían las visas. (…) Llegamos al aeropuerto y nos impidieron salir porque no teníamos visa de tránsito para pasar por donde mismo entramos. Yo entré desde Punta Cana hasta Fráncfort, transité y me dieron el paso de tránsito. Llegué de Fráncfort a Estambul, sin visado ni nada. (…) Cuando intentamos volver a la Dominicana, las autoridades turcas nos impidieron salir del país porque no teníamos una visa de tránsito. (…) La segunda vez venimos con todo listo, de nuevo nos pararon, y la tercera vez, igual. Fue allí que nos dimos por vencidos, sin dinero, sin lugar dónde vivir, ni nada y valiéndonos de lo poco que podían mandarnos nuestros familiares para el sustento de la comida. Nos mandaban mil pesos dominicanos, el equivalente a cien liras y así nos sustentábamos. Tanto así que tuvimos que dormir en un parque en tres ocasiones.”

Marcos, Estambul. Noviembre 2019)

Varios migrantes relatan que por este motivo quedaron varados en Turquía, sin permiso de estancia ni dinero para pagar el viaje de regreso a sus países.

Exposición al mercado del trabajo informal

Para muchos latinoamericanos, es difícil conseguir empleo en Turquía, toda vez que difícilmente contratan personas sin estancia legal, situación que los empuja a vivir en exclusión social y precariedad. Suelen compartir apartamentos o habitaciones pequeñas, en donde viven hacinadas hasta 8 o 10 personas que carecen de medios económicos para sustentar sus necesidades básicas. Algunos han conseguido empleos en fábricas textiles y hoteles, laboran de 12 a 14 horas diarias y ganan entre 1200 y 1800 liras mensuales (€160 – €270). Esta cantidad resulta insuficiente para cubrir sus necesidades más básicas.

Mauricio es un migrante boliviano que desdehace meses trabaja en una maquiladora de trajes de etiqueta y esmóquines porque no encuentra un empleo mejor.

“Trabajamos en una fábrica de textiles de lunes a sábado de ocho a veintidós. (…) Los trabajadores turcos nos denigran, el patrón nos trata como animales y nos grita constantemente: ‘¡çavu, çavu!’ – ¡rápido!, ¡rápido! (…) No nos permiten sentarnos ni un segundo, mucho menos conversar mientras trabajamos (…) Tenemos media hora para almorzar y media para la cena, pero la comida no es fresca, porque la guardan de días anteriores. Imagínate que hasta nos han dado comida echada a perder.”

Mauricio, Estambul. Noviembre 2019

También las diferencias salariales difieren en base al género. En estas esferas laborales, las mujeres perciben hasta un 25% menos por realizar labores similares. No solamente los migrantes irregulares Latinoamericanos manifiestan que la necesidad los empuja a aceptar condiciones laborales de explotación que hasta definen como peores que en sus propios países de origen.

Push-backs en la frontera entre Turquía y Grecia

Esforzándose por salir adelante, varios de estos migrantes latinoamericanos intentaron llegar a Grecia contratando facilitadores que en 2019 cobraban entre €700 y €2500, dependiendo del viaje. Relatan que, al ser aprehendidos, fueron víctimas de abusos y vejaciones por parte de la policía griega y devueltos a Turquía por paramilitares helénicos encapuchados. Nunca fueron escuchados para determinar su derecho a solicitar asilo en la UE, recibieron abusos verbales y fueron golpeados brutalmente a patadas y con palos de madera. Al ser devueltos a Turquía, se convirtieron también en víctimas de abusos y maltratos por parte de las autoridades turcas.

Así lo relata el testimonio de Andy, un dominicano de 32 años que intentó cruzar la frontera turco-helénica en las inmediaciones de Edirne, quien narra el terror y sufrimiento que experimentó junto a sus compañeros migrantes a lo largo de esta ruta. Su relato, constituye una denuncia pública que él mismo redactó y envió a las Naciones Unidas, con la esperanza de ser escuchado y que el mundo se entere de lo que él y sus compañeros experimentaron:

“(…) Están pasando cosas graves en Grecia en los pueblos fronterizos, incluso están muriendo personas, producto de lo que les está pasando en este territorio, y duele ver familias y bebés maltratados por los griegos. Es una emergencia. Que intervengan por los inmigrantes, están siendo torturados peor que esclavos y enfrente de sus familiares. (…) Nadie deja su país por gusto, sino por lo que sufre y allí los están matando a torturas, y luego los regresan de noche (…) sin distinción y sin investigar las razones por las cuales emigran. (…) Los maltratan sin compasión alguna. Por favor, somos seres humanos, no animales, por amor a Dios, no lo permitan, porque muchos mueren en la travesía producto de los golpes que les propinan. Por favor, pónganles un alto a los griegos, (…) manden infiltrados e investiguen, no dejen que sigan maltratando a los inmigrantes.”

Andy, Edirne. Octubre 2019

La denuncia de Andy devela una faceta de la violencia estructural que deja al descubierto la realidad experimentada por muchos migrantes al cruzar esta frontera sin permiso, al tiempo que los gobiernos europeos se hacen de la vista gorda, a pesar de tener conocimiento de graves violaciones a los derechos humanos. A esta forma de devoluciones hacia Turquía se les conoce también como push-backs y son ilegales, en virtud de que violan las leyes internacionales y directamente excluye a cualquier candidato al asilo, violando lo estipulado en la Convención de Ginebra de 1951. Por si fuera poco, recordemos que Turquía solamente reconoce el derecho al asilo bajo los criterios de esta convención a ciudadanos europeos. Con relación a este postulado, Andy enfatiza:

“A mí me gustaría que aquellas personas que hacen las leyes o están al cargo de ver por estas cosas se hicieran pasar por migrantes, fueran allá y se pasaran la frontera como nosotros, para que ellos sientan lo que sentimos y los maltraten como nos maltratan a nosotros. (…) Así podrían convencerse de que no estamos inventando historias y darse cuenta de que es una realidad que vivimos los migrantes, para que todo el mundo vea cuánto sufrimos.”

Andy, Estambul. Noviembre de 2019

En el comentario de Andy, se percibe la frustración y el cólera que dichos maltratos infunden en los migrantes, dejando entrever la consumación de un ‘castigo ejemplar disuasorio’ que tiene la finalidad de infundir terror y evitar su retorno a la frontera, para intentar cruzarla de manera irregular.

Trabajo sexual como medio de supervivencia

Pasemos ahora al caso de algunas mujeres migrantes latinoamericanas que viven en condiciones precarias y se dedican al trabajo sexual, al ser una de las únicas maneras que tienen para salir adelante. Hubo quien fue víctima de trata, otras engañadas y traídas hasta Turquía con la promesa de conseguir trabajo fácilmente, supuestamente porque el nivel de vida era más alto que en Latinoamérica y fácilmente se conseguía empleo. A otras les dijeron que sería más fácil llegar a Europa vía Turquía, o bien que Turquía era ya parte de la UE. Ahora, deben negociar su salario con los clientes, el cual oscila entre las 60 y 120 liras (€10-20) por relación sexual o entre las 250 y 500 liras (€38-75) por todo el acompañamiento nocturno. Cuentan que suelen buscar a sus clientes en la calle, discotecas o bares, y la mayoría trabajan únicamente en hoteles, en virtud de que se sienten inseguras en domicilios particulares. Prefieren clientes latinoamericanos o africanos, porque cuentan que los hombres turcos las tratan muy mal y pueden llegar a ser muy violentos. En ocasiones, los clientes no quieren ir a hoteles, ni les quieren pagar, les exigen tener relaciones sin protección o hasta las golpean cuando no acceden a sus exigencias. Otros abusan de alcohol y drogas, lo cual pone en peligro integridad de estas mujeres, especialmente cuando los compradores de sexo devienen agresivos y violentos.

Rocío es una mujer dominicana de poco más de 30 años. Abandonó sus estudios en Filosofía porque le prometieron un buen empleo en Turquía, a través del cual podría ayudar económicamente a sus familiares que estaban en gran necesidad. Sus padres son agricultores de edad avanzada y viven con ingresos económicos muy bajos. Al llegar a Turquía de pronto se vio sola y se enteró de que la habían timado, no había ningún trabajo esperándola y tenía pocas posibilidades de conseguir uno. Esta realidad la obligó a dedicarse al trabajo sexual por primera vez en su vida, siendo ésta la única opción disponible para cubrir los gastos de su alquiler y sus necesidades básicas:

“Aquí en Turquía, he tenido que tirarme a las calles. (…) En una ocasión, durante el trabajo con un cliente turco, me encerró en su casa y me rompió el chip del teléfono para que no tuviera comunicación con nadie. Después me amenazó y me quitó el dinero que me había pagado porque no quería cumplir con todo lo que él quería. El tipo no terminaba, pero yo ya no podía más, estaba agotada (…) Mi mayor temor era que me violara sin condón, que me diera un golpe o que estuviera enfermo, porque estaba embriagado y drogado. (…) Como yo ya no quería estar con él, se puso violento, me sacó de su casa, desnuda, me lanzó la ropa afuera y tuve que vestirme en la escalera. Salí de allí llorando a buscar un taxi y no sabía a dónde ir. (…) No es fácil la vida aquí, yo lo sé, pero ni a mi peor enemigo le desearía que viniera a este país.”

Rocío, Estambul. Noviembre 2019

Estas mujeres latinoamericanas enfrentan relaciones de poder que las ponen en peligro, especialmente cuando se encuentran en manos de hombres que las maltratan y las amenazan con reportarlas a la policía por no tener permiso legal, dejándolas aún más vulnerables y desamparadas. Asimismo, este trabajo las expone a graves daños psicológicos y riesgos a su salud física, porque siempre tienen que cuidar que los clientes no rompan o se saquen los preservativos, poniéndolas en riesgo a enfermarse o embarazarse. Para los latinoamericanos en situación irregular es difícil acceder al sistema sanitario público, toda vez que su condición migratoria, limita su acceso a la atención médica.

Muchos migrantes remitían con dolor a la historia de Carmela, una joven latinoamericana que realizaba esta actividad, contrajo VIH y no tuvo acceso ni a la debida atención médica ni al tratamiento. Los medicamentos antirretrovirales y el control del VIH son costosos y no se ofrecen a personas sin permiso de residencia o estado de protección internacional en Turquía. Viviendo bajo estas circunstancias las condiciones de Carmela empeoraron y la desesperación de sus amigos y familiares los empujó a hacer una colecta de dinero para ayudarla regresar a su país y recibir cuidados especializados. Su consulado no quiso ayudarla y la persona que le tramitó el viaje engañó a los familiares, utilizando una tarjeta de crédito sin fondos y falsificando la reservación del vuelo. Sin saberlo, cuando su mejor amigo la llevó al aeropuerto, no pudo abordar el vuelo porque el pago no estaba confirmado, lo que la dejó sin dinero y varada en Turquía. Poco tiempo después, Carmela falleció a causa de complicaciones que la enfermedad le trajo. Las autoridades trasladaron su cuerpo a una montaña en las afueras de Estambul en una bolsa negra y fue inhumada en una fosa común, sin haber tenido un funeral.

Brenda es una joven dominicana que cuando llegó a Turquía, fue forzada a ingresar al trabajo sexual por la persona que le cobró €3,500 para traerla a esta país, con la promesa de que posteriormente llegarían a España. Después de narrar su relato, Brenda resumió sus miedos más profundos con lágrimas rodando por su rostro, mientras sus ojos nublados miraban al vacío:

“No quiero que me pase lo mismo que a Carmela y que me echen como perro a una fosa común en una bolsa negra. Tampoco quisiera que algún día me den una puñalada, me desangre y quede allí sola, sin haber vuelto a ver mi país y a mi familia antes de morirme. Estos son los temores más grandes que vivo aquí.”

Brenda, Estambul. Noviembre 2019

El suceso anterior ha marcado la memoria colectiva de una parte importante de la comunidad Latinoamericana en Estambul. Muchos migrantes contaron este relato desgarrador con tristeza y desesperación, mientras recontaban su miedo a morir en tierras tan lejanas, sin posibilidad de regresar a sus países para reunificarse con sus padres e hijos.

Encarcelamiento y quebranto de la vida

Otro caso remite a los ex-convictos que han quedado varados en Turquía y con pocas posibilidades de regresar a sus países. Este apartado reportala historia de Lina y Toño como ejemplos epítomes de las realidades que viven numerosos latinoamericanos. Ellos dos son una pareja de 48 y 39 años de Paraguay y Venezuela que no soñaba con viajar a Europa, ni en ganar en euros. No obstante, ambos se convirtieron en migrantes irregulares a causa de circunstancias inesperadas. Toño es originario de Caracas y creció en el seno de una familia de bajos recursos, mientras tina fue abandonada por su madre y creció con un padre soltero que era músico y trabajaba como militar. Ambos tenían deudas en sus países, enfrentaban las presiones de sus acreedores y tenían que sustentar a sus hijos y padres. Dejaron Sudamérica forzados por las amenazas de sus prestamistas quienes exigían de manera inmediata la devolución de su dinero, ofreciéndoles la posibilidad de pagar sus deudas transportando un paquete de droga a Turquía dentro de sus cuerpos. En teoría, tal acuerdo condonaría completamente sus deudas y supuestamente les brindaría a su retorno, estabilidad económica junto a sus seres queridos. Al comenzar la odisea, no estaban conscientes de las posibles consecuencias de sus actos, pero a su llegada a Estambul, la corte los condenó a penas de 8 y 12 años de prisión por cargos de narcotráfico, terrorismo e intento de homicidio. Lina y Toño pasaron muchos años en la prisiones de alta seguridad, sufriendo condiciones denigrantes y enfrentando el resquebrajamiento de sus existencias y núcleos familiares. Lina cumplió su sentencia de ocho años, pero al salir del centro de readaptación social, no tuvo acceso a regularización migratoria ni residencia, por lo que ahora se encuentra sin documentos de viaje para salir de Turquía. A su arribo a este país, la arrestaron con su bebé de seis meses, quien enfermó de leucemia infantil durante el tiempo que la acompañó en prisión. A la edad de 6 años, las autoridades turcas los separaron y remitieron a la niña a una institución para su educación y cuidado. Ahora tiene 11 años, no habla español, fue convertida al Islam y solamente le permiten visitar a su madre una vez cada tres semanas por espacio de ocho horas. Lina la extraña mucho, se siente sola y lo único que quisiera es volver a ser una madre como cualquier otra, a quien su hija la hace feliz cuando está cerca o rabiar cuando se porta mal. Su semblante refleja la nostalgia que siente por su hija y lo mucho que sufre por tenerla lejos, mientras la vida pasa lentamente. Junto con Toño, guarda la esperanza de ahorrar dinero para reunirse con su hermana que le espera en España.

Lina manifiesta su dolor al subrayar las dificultades que enfrenta para llevarse a su hija de Turquía por vías legales, toda vez que las autoridades turcas consideran que no puede sustentarla, ni posee medios económicos para cubrir los gastos de repatriación. Tampoco puede regresar a Paraguay porque su ex-pareja la ha amenazado con quitarle a la niña e incluso con asesinarla, por lo que está intentando reunir el dinero para embarcarse a Europa, pero le consterna imaginar el viaje en lancha a las islas griegas. Su mayor preocupación recae en proteger la integridad de su hija y en varias ocasiones le ha manifestado a Toño que en caso de naufragio la deje ahogarse a ella, pero salve a la niña porque es la flor de la vida y merece una existencia digna que ella nunca pudo darle. Al mismo tiempo, Lina dice sentirse afortunada cuando percibe el amor que Toño siente por su hija, aunque este no sea su padre biológico. Sin embargo, Lina ya no puede trabajar debido a que recientemente le diagnosticaron tumores y precisa una operación que no puede pagar, toda vez que su situación irregular le impide acceder al servicio médico gratuito.

“Me siento muy triste, ya se me acabó la vida y quiero irme lejos, pero no puedo dejar a mi niña aquí. (…) Yo estoy sola, estoy así, acabada, jodida de la vida, deprimida (…) No sé qué voy a hacer de mi vida, porque estamos sin dinero (…) Siento que me estoy muriendo en vida, quiero alejarme de la gente, de todo el mundo y vivir sola. (…) Ya no quiero nada de la vida, todo fue puro sufrir y pocos minutos de alegría, creo que yo no nací para ser feliz. (…) Ahora estoy muriendo de dolor y tristeza (…) Ya no quiero nada de la vida porque nadie me espera, sólo una hija pequeña que está en un orfanato. Para ella, sí voy a estar hasta los últimos días que me queden, pero ya no quiero vivir así como estoy.”

Lina, Estambul, Octubre 2019

El poco dinero que Lina ahorró, lo ha gastado en estudios médicos y calmantes, los cuales al menos atenúan los fuertes dolores que le aquejan. Se siente desesperada, está deprimida y llora amargamente con frecuencia. Sus palabras y semblante reflejan la desesperación y sufrimiento que siente, dejando entrever los efectos de la irregularización migratoria que, en ocasiones, se presenta sin previa planeación o aviso. Después de dejar prisión, Lina y su familia se convirtieron en migrantes de-facto y ahora se encuentran viviendo en limbo y atorados en Turquía. Lo único que desean, es salir del país en el que ya no quieren estar, sin embargo, no pueden.

Conclusiones

Para los migrantes latinoamericanos en situación irregular en Turquía, las condiciones de vida son duras y muchos de ellos son víctimas de violencia estructural y social por el simple hecho de ser extranjeros. Sus caminos de vida los llevaron a experimentar realidades inesperadas y dolorosas que los mantienen atrapados en Turquía con pocas posibilidades de abandonar el país. No obstante, todos ellos mantienen la esperanza de reconstruir sus vidas, saludar a sus amigos, comer sus platos típicos, bailar salsas y visitar a aquellos familiares que no ven desde hace una década. Para concluir, las historias aquí presentadas representan sólo algunos ejemplos del limbo invisible en donde se encuentran atorados muchos latinoamericanos que voluntaria o involuntariamente se convirtieron en migrantes a su llegada a Turquía. Aunque en teoría la migración representa una lucha por alcanzar una vida digna, el caso de Turquía demuestra que estos preceptos, más que una realidad palpable, constituyen una utopía cada vez más inalcanzable.

Gianmaria Lenti, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City, Mexico

Bernardo López Marín, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia