Via BBC – At Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesbos, there is deadly violence, overcrowding, appalling sanitary conditions and now a charity says children as young as 10 are attempting suicide. The Victoria Derbyshire programme has been given rare access inside.

“We are always ready to escape, 24 hours a day we have our children ready,” says Sara Khan, originally from Afghanistan. “The violence means our little ones don’t get to sleep.”

Sara explains that her family spend all day queuing for food at the camp and all night ready to run – in fear of the fights that break out constantly.

Conditions are so appalling that charities have actually left in protest.

The place smells of raw sewage, and there are around 70 people per toilet, according to medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF).

Some people live in mobile cabins, but rammed in-between them all are tents and tarpaulin sheets – homes for those who cannot obtain any official living space.

The camp is also now sprawling into surrounding countryside. One tent houses 17 people – four families under one canvas.

There are currently more than 8,000 people crammed into Moria camp, which was supposed to house around 2,000.

A mum describes faeces on the floor of the shelter that she lives in with her tiny 12-day-old baby.

The violence in the camp is extreme. In May, hundreds of Kurdish people fled because of a huge battle largely between Arab and Kurdish men.

Ali, who has now left the camp, says when he got to Moria with his family “we found that there was already existing sectarianism and racism, whether it was between Sunnis and Shias, or Kurds, Arabs and Afghans”.

He adds that conflict between rebel groups in Syria has also landed inside the gates of the refugee camp.

“It’s like the war in Syria and even uglier. We heard about rape cases in there, sexual harassment,” he says.

On the day we are filming at Moria, yet another fight breaks out in the lunch queue for food. Two people are stabbed – others suffer panic attacks witnessing it.

Nearby medical workers are put on standby at MSF.

The charity initially left the island in protest at conditions, but has now opened a clinic just outside the gates because the need was so great.

The children they are treating have skin conditions caused by the poor hygiene inside, and respiratory diseases from tear gas fired into the camp by police to quell fights. Mental health problems are rife.

The workers say they have had to deal with children as young as 10 attempting suicide.

“It’s something we’re seeing constantly,” says Luca Fontana, Lesbos co-ordinator for MSF, adding that they are reporting the conditions to the UN refugee agency UNHCR and Greece’s ministry of health.

“Despite the fact that we push to move these children to Athens, as soon as possible, it’s not happening. Those children are still here.”

The camp opened in 2015 and was initially designed as a transit post for people to stay for a matter of days – but some have been here for years.

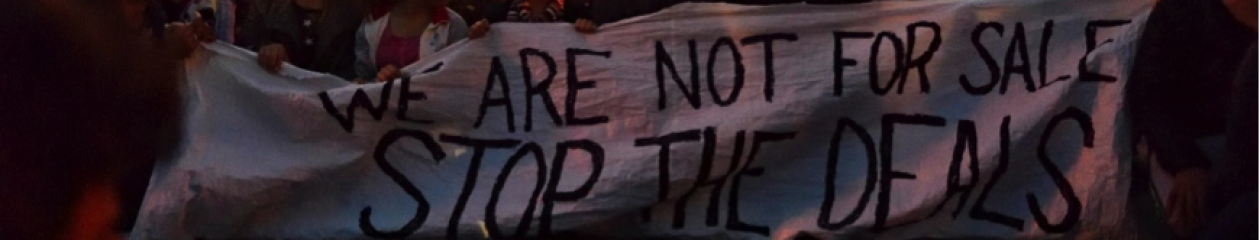

It is controlled by the Greek government, and the overcrowding is because Greece is enforcing the EU’s “containment” policy, keeping people on the island rather than transferring them to the Greek mainland.

It is part of the EU-Turkey deal which aims to return thousands of refugees to Turkey, and it has been in force since March 2016.

From then to July 2018, according to EU figures, 71,645 new refugees arrived in Greece by sea and only 2,224 have been returned to Turkey.

George Matthaiou, a Greek government press representative on Moria, concedes conditions are terrible, but blames the EU rather than Greece.

“We don’t have the money. You know the situation of Greece, economically,” he says.

“I want to help but I can do nothing, because the European Union closed the borders.”

Back at the MSF tent, Luca Fontana, who has worked all over the world in conflict zones, says the camp is the worst place he has seen in his life.

He worked during the Ebola outbreaks in West Africa but says, “I’ve never seen the level of suffering we are witnessing here every day”.

“Even those affected by Ebola still have the hope to survive or they have the support of their family, their society, their village, their relatives.

“Here, the hope is taken away by the system.”