By Garib Mirza – Garib Mirza is a freelance researcher, whose studies focus on the ongoing conflict in Syria and recently on the Syrian refugees. He has worked for independent Syrian research centers and think tanks.

The European Dream

‘It’s Europe!’ a Syrian youth responded when a France 24 reporter asked him in 2014 why he and others set out on the arduous path to Europe. ‘It’s Europe!’ seems enough of an answer to the question and perhaps it is the best expression of many refugees’ and asylum seekers’ ‘European Dream’.

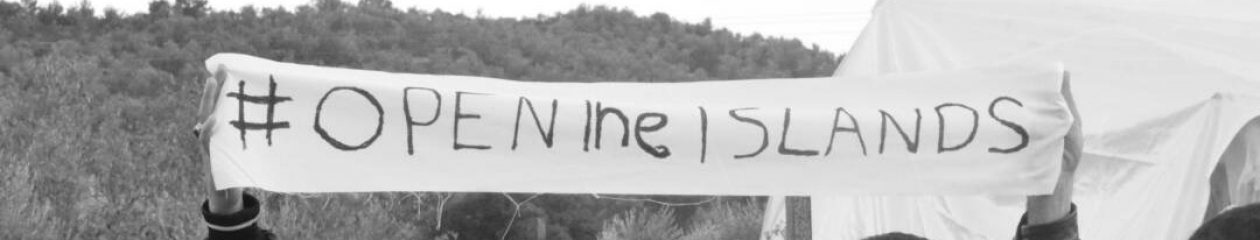

Since the 2015 influx of Syrian refugees, people on the move have represented Europe as a kind of heaven which can only be reached via a risky and difficult journey. Syrian refugees have continued to cross the Aegean Sea and Bulgarian borders in hopes of reaching Greece. Many then follow the Balkan route to their preferred countries of destination in Western Europe and Sweden. On the way, they are vulnerable to exploitation by smugglers, abuses and violence on their insecure journey or at the border – and many have simply drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. In spite of all this, Syrian refugees persist in their struggle to reach Europe.

Dual dynamics continue to ‘push’ and ‘pull’ refugees to take these risks. On the one hand, Europe is perceived and represented as a safe place, a happy place. On the other hand, Syria’s neighboring countries are experienced and represented as difficult places with harsh conditions. It is not uncommon to hear refugees say that there is ‘nothing here for us’ and describe their lives in Turkey as ‘unbearable’ and even as bad as death at sea. The same might be said about refugees who live in Lebanon and Jordan, where they suffer from difficult conditions and various constraints.

In Western European countries and Scandinavia, paid language courses, monthly allowances, the clear legal definition of refugee status and the right to travel documents (the majority of Syrians in Syria’s neighboring countries have no valid papers that would allow them to travel) make Europe a place of safety for refugees. Moreover, Europe represents a place where a person can achieve her/his dream.

The Middle East in Istanbul

However, this is just one part of the picture. Not all of the 3 million Syrians living in Turkey are ‘stranded’ there as a result of the 2016 EU-Turkey deal on refugees or because they do not have enough money to pay a smuggler.

There is a counter-narrative to the European Dream, which points to the choice to stay here in Turkey. This is a less ‘mythical’ move, but it may be more complex.

In Istanbul’s Kadiköy, at a café owned by a Turk and run by young Syrians, you order tea, coffee, some food and pay what you want. In that small utopian enclave, I met Nur, a young Syrian from Damascus, who had escaped because of mandatory military service. He is a musician and an architect. Nur explained why he is here and intends to stay: ‘We have lost Damascus, we have lost Beirut, Cairo, Mecca, Bagdad, and Tehran. We have only Istanbul now as the last Eastern capital to be sustained’.

Nur’s ‘we’ refers to the Middle Eastern people, who share a rich and diverse culture extending from Cairo to Istanbul. For him, these capitals were ‘lost’ under dictatorship and a one-dimensional, oppressive culture. Nur is one of countless Syrians who live in Istanbul and feel a deep sense of belonging to this city. Syrians I have met and whose stories I have read on the blog ‘Why am I in Turkey?’ frequently express a similar sense of belonging to Istanbul: ‘I feel like I am in Damascus’, ‘I belong to here’, ‘Istanbul is strongly connected to Damascus’. Notably, such belonging stems from making a link between Damascus and Istanbul. They note that historically, the two cities were part of the same empire for over 400 years and had strong cultural ties. Another source of belonging is the belief in a wider shared Middle Eastern identity, which is expressed in Istanbul.

A sense of belonging

Syrians’ sense of belonging in/to Gaziantep is slightly different from Istanbul. Gaziantep, a city in southern Turkey, has strong ties to Aleppo. It is home to a large number of Syrian refugees, the majority of whom are originally from Aleppo. ‘It is the last latitude, I cannot go beyond it’, a fifty-year-old Syrian told me. A left-wing activist who had struggled against Assad, he meant that Gaziantep is as far from Aleppo as he can go.

This sense of belonging seems to contribute to some staying in Turkey, rather than heading to Europe, even if the life here is more difficult and uncertain for refugees. ‘Although all my friends are in Germany now – as refugees – I want to stay here in Istanbul and to be a part of this community’, a Syrian refugee said.

There is another factor that leads Syrians to stay in Turkey. Turkey and particularly Istanbul and Gaziantep seem to offer an ‘alternative land’ for displaced Syrians where they run their civil activities after being expulsed from Syria. Turkey hosts tens of Syrian NGOs, political parties, independent media that developed during the war, and many schools where Syrians were educated until they were closed recently. It would seem that Turkey hosts a ‘small Syria’, as one Syrian said. This ‘small Syria’ offers an encouraging environment to pursue different jobs and activities or to connect with Turkish and Western experts, which results in significant political, social, and financial remittances to Syria.

‘Here I am active, you know! I may become homeless, but I feel that I didn’t escape and leave my friends behind. At least I didn’t escape that much. If I go to Europe, it means that I avoid my responsibility’, a thirty-three-year-old woman from the Syrian resistance against Assad told me.

Beyond the European Dream

Beyond the narrative of a ‘European Dream’, there is a counter-narrative of those who stay in Turkey. It refers to the sense of belonging to a shared culture, which could be lived in the cosmopolitan center of Istanbul, beyond ethnic and linguistic difference. The counter-narrative also builds on Syrians’ ability to pursue a broad range of activities and work in relation to the situation in Syria. Syrians perceive Turkey to offer fertile ground for practicing their civil, political, cultural, and economic activities. In their eyes, this would be ‘strangled in bureaucratic Germany’, as a thirty-five-year-old Syrian artist told me. The ‘European Dream’ might be reframed as narrative of seeking safety, while its counter-narrative frames Turkey as a place of activity.