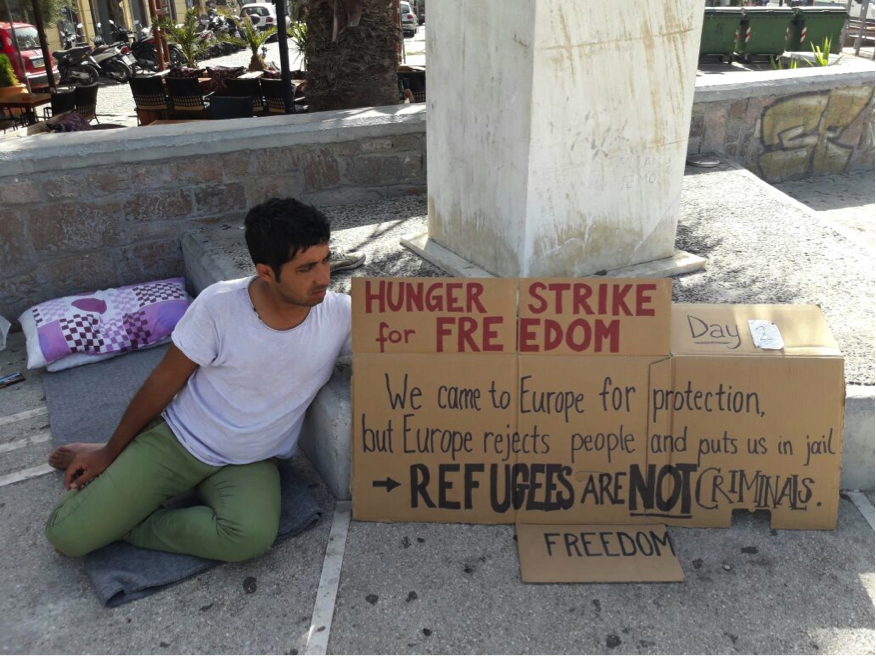

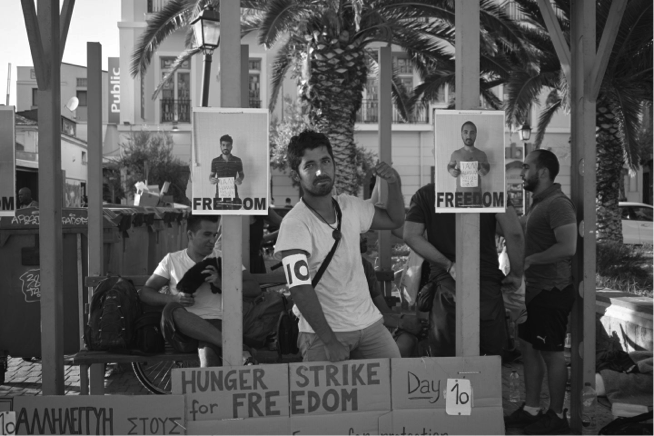

For 14 days, refugee activist Arash Hampay has refused food. On the Greek island of Lesvos, he sits on the central square of the town Mytilini surrounded by shops, cafés and tourists, presenting a sign stating “Refugees are not Criminals”.

He is exhausted but determined to continue his hunger strike until the end. His open statement leaves no doubt:

“We shall continue our hunger strike until the prisoners in Moria camp are released, regardless of the consequences for us. A life without freedom is worthless and meaningless for us. You must release the refugees or we shall end our lives in front of your eyes and the people’s eyes. We are waiting for you. The people are waiting for you. You must free us or else be responsible for our death. We will keep waiting until the last drop of life falls from our bodies.”

The barbed wired camp Moria on Lesvos has been declared a migratory hotspot by the European Union. Since the EU-Turkey Statement came into force on March 20, 2016, refugees arriving on the Greek islands are prevented from moving on to the mainland. Under most precarious conditions, they are kept in tents or containers inside Moria. Some of them have been there for more than a year. Although it looks like a high-security prison, most people are allowed to leave the camp during daytime. But some refugees are also detained day and night in Moria’s prison “Section B”. Arash’s brother Amir is one of the detainees in Moria’s pre-removal prisons.

Eight months ago, the two brothers arrived on Lesvos Island. They came to seek asylum after they were repeatedly arrested and threatened by the Iranian police for their work in a human rights organization supporting children’s, refugees’ and women’s rights. Arash was severely tortured several times and his teeth and tendons were broken. Eventually, the brothers had to flee the country to save their lives. At first they tried to stay in Turkey, but as human rights activists they were once again threatened by the government. They only had one choice left: crossing to the Greek islands in a fragile rubber dinghy.

After arriving on Lesvos, they experienced long months of deadlocked waiting behind barbed wire. They had to queue behind 1500 people for distributed food for hours every day. In winter, they had to sleep in tents covered in snow and saw three people die in the cold. They saw a woman and a girl burn to death in front of their eyes when their gas cooker exploded and the camp caught fire. But they believed this hell would end once they got asylum.

Yet suddenly, Amir was arrested like a criminal. When the two brothers went into Moria to renew their documents for the following month, Amir was immediately taken into custody and informed that his asylum application had been rejected. His brother still cannot believe the decision:

“We have both the same story, have done the same work, and have come to Europe together. Why was he rejected and I was not?”

Amir was imprisoned together with many other asylum-seekers. Generally, some asylum-seekers are detained because their asylum application has been rejected, others because the police considers them as “trouble makers”. Again others are only arbitrarily imprisoned because of their nationality, since the police sweepingly classifies them as migrants “with an economic profile”. Algerians, Tunisians, Moroccans, Pakistanis and Bengals are particularly affected. But there are also people detained who have agreed to the so-called “voluntary return” to their country of origin or to Turkey. In practice, these people have to undergo the same procedure as deportees: They are imprisoned, shackled and deported on a ferry. Many of them have only given up their right to asylum because the unbearable living conditions and the lack of perspectives in the Moria camp have driven them into despair.

After two weeks in prison, Amir was informed that he would be sent to Athens together with his fellow prisoners. However, they were brought on a ferry to Turkey. None of the deportees were allowed to make a phone call or tell anybody about the deportation. Nevertheless, Arash found out about the imminent “return” of his brother to Turkey. He mobilized friends, activists and lawyers who came to the port and prevented Amir’s deportation at the last minute.[1]

The coordinator of the Legal Centre Lesbos, Lorraine Leete, was one of the people responding to Arash’s call for help. She explains why the deportation was highly problematic:

“Amir had passed the admissibility phase of his application and the Greek government found that Turkey was not a safe country for him. But then his asylum claim and his appeal were rejected. So – putting aside the question whether he has a valid asylum claim – they were going to deport someone to Turkey they had just found Turkey is not safe for.“

In addition, Amir’s lawyer had already filed a petition to suspend the deportation in order to challenge the decision before an administrative court – which was simply ignored. Amir’s deportation could only be halted by means of an emergency petition with the European Court of Human Rights.

Once Amir was taken off the ferry, it left immediately. Everyone else was deported in handcuffs – without further checks. They did not have a brother rushing to help them last minute.

The lawyer Lorraine Leete is deeply concerned about this deportation practice. She explains:

“One really worrying thing about the deportations that are happening on Lesvos now is that there is no record of who is being deported until after the fact and there does not seem to be any sorts of internal checks to make sure that everyone who is deported actually has exhausted their remedies in Greece. Everything goes back to a list of names that the Greek Asylum Service gives to the police and the police gives to FRONTEX. They also share it with the European Commission but there is no oversight on the question if the deportations are actually legal. This is a huge problem, because often we do not know who has been rejected and who is sent back to Turkey or to their home countries. So it is probable that there are individuals who are illegally deported without our knowledge.”

Since the EU-Turkey agreement, 1826 people have been returned to Turkey in this way.[2]

Although Amir was taken off the boat, he is not free today. For two months, he has been waiting in jail for the decision of his appeal. Together with his brother Arash and other detainees, he went on hunger strike. With temperatures up to 40 degrees, they only drink water. The police prevents supporters to visit them and supply them with sugar and salt against dehydration. They also do not receive any medical attention.

“No one wants to take responsibility. We are like a football among the European Union and the Greek government.”

The shady practices of deportations are not a failure of the Greek state but the result of the European migration politics. Since the agreement between the European Union and Turkey on March 20, 2016, the situation for refugees on the Greek islands has dramatically deteriorated.

Following the statement, a new asylum law was adopted in Greece providing a fast-track border procedure for the Greek islands only. Consequently, most refugees are not allowed to leave the islands during the entire asylum procedure. To speed up the process, officials from the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) were sent to the islands to assist the Greek Asylum Service. However, even with their limited support the asylum offices on the islands will hardly be able to process thousands of asylum applications in the near future.

This leaves people who have been kept behind barbed wire for more than a year in a desperate state of limbo. A young refugee from Ghana describes the impact on refugees in the Moria camp:

“Moria is a place where you cannot do anything and where you know nothing about your future. People decide and think for you: It is decided what you eat, where you sleep, what you say and when you are deported. Most of us who arrived here were physically and mentally healthy and strong. But after two or three months, the conditions in this camp make us sick, many people get mental problems, they are traumatized. Children are growing up here and watching people injure themselves and imitate it. How can this be possible?

No one wants to take responsibility for the situation. When we demand for our rights, the EU accuses Greece and Greece the EU. We are like a football in-between the European Union and the Greek government.”

Since the enforcement of the EU-Turkey agreement, many asylum seekers have to prove that Turkey is not a safe country for them in an admissibility interview – even before their asylum applications are considered. This affects mainly Syrians, and, since the beginning of 2017, also people from countries with an asylum recognition rate of more than 25%, e.g. from Iran, Iraq, Congo and Eritrea. Moreover, connected to a pilot project, border-crossers from nationalities with low recognition rates, such as Pakistan and the Maghreb countries, also have to undergo an accelerated procedure, causing rejections to skyrocket.[3] So far, most Syrians have been rejected on admissibility grounds, imprisoned and returned to Turkey, while most of the cases of non-Syrians opened in 2017 are still pending. However, 1826 people from different nationalities have been brought to Turkey since the EU-Turkey deal has been concluded, some of them under a Greek-Turkish readmission agreement.[4]

“We had cases where the Greek Asylum Office relied on Wikipedia to make their decision.”

The asylum and admissibility interviews conducted by EASO and the Greek Asylum Service have been strongly criticized. The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) recently concluded: “EASO officers fail to respect core standards of fairness”.[5] Similarly, the work of the Greek Asylum Office shows serious shortcomings, as Lorraine Leete reports:

“We have seen that the Greek Asylum Service relied on Wikipedia for making decisions. For one of our clients they claimed they could not find his village in Google Maps although it was just a spelling mistake. They use those really minor things to deny people refugee status.”

The problem of the large-scale rejections of asylum applications was also reflected in the decisions of the Greek Appeals Committees. Their decisions clearly opposed the classification of Turkey as “safe third country”. By the end of November 2016, the appeals committees revised the first instance rejections on admissibility grounds in 97.9% of cases. However, pressured by the European Commission, the committees were finally replaced by the so-called “Independent Appeals Committees”. Subsequently, the rate of revisions on first instance rejections dropped to 0.4%.[6]

“After their return, all non-Syrian refugees are detained in readmission centres.”

In Turkey, refugees are far from safe. The country has only ratified the Geneva Convention on Refugees with a geographical limitation. Therefore, only Europeans can be granted asylum in Turkey. Syrians can apply for a “temporary protection status” which, however, by no means grants them the same rights as a “refugee status”.

All other migrants being sent to Turkey are surrendered to a particularly gloomy future. Deman Güler, a Turkish attorney specialized in asylum law explains:

“All non-Syrians are detained after their return in so-called repatriation centres. Those places are the worst accommodations for refugees in Turkey. There are many examples of people being held in an enclosed space for 23 hours a day. “

This way, people who have escaped war, persecution and imprisonment are being sent back to detention. They are usually held in the prison-like centres until they are deported back to their countries of origin or agree to “voluntary return”, explain Deman Güler and Lorraine Leete. They also know examples of Syrians who were imprisoned and deported or forced to return ‘voluntarily’ to their home countries.

“We came to Europe for protection, because we were tortured, because our lives were in danger. But you are treating us like criminals.”

Since the introduction of the EU-Turkey agreement, the European Union has simply outsourced the human rights violation of deporting refugees seeking protection back to their persecutors to Turkey.

Under the name of “return”, people who have fled war and persecution are surrendered to Turkish prisons. After long months of imprisonment, most of them are, in one way or another, returned to the places they fled from.

A refugee activist concludes:

“If the European Union decides that human rights are not valued in Europe, they should send us back the day we arrive, rather than imprison us for months and years like criminals.”

The human rights activist Arash Hampay refuses to accept the detention and deportation of his brother to Turkey. In solidarity with the detained hunger strikers he has remained without food in the blazing sun for eleven days. If Arash and Amir were sent back to Turkey, they would most probably be detained and then deported back to Iran – which could, at worst, result in their death.

In the town of Mytilini, Arash was repeatedly threatened by the police and the vice mayor of Mytilini. He was told to stop his protest and to go back to his country. However, he is supported by other refugees and activists from different organizations. He does not give up fighting for their human rights, as much in Iran and in Turkey as on the soil of Nobel Peace Prize Winner “European Union”.

Arash demands the immediate release of his brother and all other detained refugees:

“We came to Europe for protection. We came because we were hurt, because we were tortured, because our lives were in danger. But instead of showing us mercy, you are treating us like criminals. Barbed wire and prison cells are not the right place for refugees.

From the day we fled the hell we were enduring in our home countries and became refugees in pretentious Europe, we have suffered the worst kinds of psychological torture. We have been humiliated and beaten by the police. We have had our human dignity stripped from us. We saw our families dying beside us and you did nothing.

How dare you speak in the beautiful slogans of human rights? How dare you talk about humanity and law and democracy? How dare you condemn human rights abuses in other countries when you are committing human rights abuses here, yourselves?

Perhaps it is because we are refugees and you do not value our lives. There is still strength in us and we are still alive. We shall continue our hunger strike until the prisoners in Moria are released, regardless of the consequences for us. Come and show us that you care about our lives. Show us that you have a conscience. Come and see the youth who you have imprisoned for seeking refuge in your country. Do not wait for them to die due to your ignorance. We are waiting for you. The people are waiting for you. We will keep waiting until the last drop of life falls from our bodies.”[7]

Last update (July, 12): Arash Hampay is today in his 14th day of hunger strike and he is still continuing. He has just published an article in the Independent about his struggle.[8]

[1] See also: HRW, 28.04.2017: ‘My Brother is Being Deported Today’ (http://bit.ly/2u7ZtTE).

[2] European Commission, 29.06.2017: Operational implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement (http://bit.ly/2jjPFQr).

[3] Hellenic Republic Ministry of Interior and Administrative Reconstruction et al.: Circular: Management of undocumented aliens in the Reception and Identification Centers (C.R.I)(http://bit.ly/2ngIEj6)

[4] European Commission, 29.06.2017: Operational implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement (http://bit.ly/2jjPFQr)

[5] Greek Hotspots: EU Ombudsman probes work of European Asylum Support Office (EASO) (http://bit.ly/2saj5pC)

[6] Asylum Information Database, 31.12.2016: Country Report: Greece, p. 41f. (http://bit.ly/2nwd9nA)

[7] See also: Legal Centre Lesbos, 30.06.2017: Arbitrary Detention in Lesbos – Refugees Driven to Hunger Strike to Protest Inhumane Conditions (http://bit.ly/2t3bXfA); Enough is Enough, 1.07.2017: Hunger Strike in Morias Detention Center (http://bit.ly/2u8dXTQ), (https://www.facebook.com/arashampay).

[8] The Guardian, 11.07.2017: I came to Greece to escape imprisonment in Iran – but now I realise that Europe is worse (http://ind.pn/2uMtlCP)