Reporting from the kritnet conference Göttingen – Part 1

The HarekAct editorial board attended the 16th kritnet conference in Göttingen between 11-13th of May. It was a very good occasion to share and exchange knowledge, meet our friends, activists and colleagues again and discuss future projects and plans. We took part in the workshop titled “Post 2015 Border Regime – Re-Stabilization of the European Border Regime after the ‘Long Summer of Migration’”. We discussed the extension of borders into the cities following the example of Istanbul; the state of the border regime and public debate on migration in Turkey; and the impact and future of the EU-Turkey statement for both Greece and Turkey. Besides the individual inputs, we had a rich collective discussion with various perspectives, information and experiences brought by activists, researchers and professionals from Germany, Turkey, Greece and Kurdish region, and we are looking forward to keep building on the ideas we had as well as the connections we built there.

Although with a little bit of delay, now we would like to share our contributions to the workshop one by one. Enjoy the inputs presented by HarekAct editors in written and updated form in our blog. Keep posted!

With the so-called “summer of migration” three years behind us, and the European borders still sealed tight, it seems a good opportunity to remind ourselves of where these migrants are currently waiting, and what has happened since then. With this intention, I will here try to present an overview of the post-2015 migration context and the related management regime in Istanbul, Turkey.

To set the time frame, it should firstly be highlighted that Turkey’s “open border” policy on the Syrian border was effectively ended by March 2015, and was replaced with the militarization of border security through the erecting of border walls.

Border wall at the Turkey-Syria border. Photo by: sabah.com.

Border wall at the Turkey-Syria border. Photo by: sabah.com.

The walls built on the Turkish-Syrian border have now been completed to a major extent, reaching 764 km in total, in addition to the 144km long Turkey-Iran border wall. Following intensified repression and clashes, particularly concentrated around the Kurdish area and within Turkey, and parallel to the increase of hope directed towards the west, the numbers of Syrians, in addition to other migrant groups in Istanbul, gained acceleration.

In addition to the implementation of the infamous EU-Turkey deal in March 2016, a further enforcement of national security and border control was fully enabled owing to(!) the coup attempt that happened in July 2016, which brought the state of emergency and several “statutory decrees” (KHK in Turkish). The following period was marked by widespread controls and restrictions, not only for Turkish citizens but also for migrants and certain structures, including those organizations providing services and support to migrants. Finally throughout 2018, migrants have remained a hot subject for both internal and external politics, starting with the Afrin operation and the resultant increased nationalist discourse, which intensified even further as the economy gave more urgent signs of collapse and the June 24th snap elections approached.

In light of this chronology, particularly bearing in the mind the impact of the closing of the borders, the EU-Turkey deal, the July 15th coup attempt, and the rising numbers migrants alongside increasing tensions within society, I would like to evaluate the context in Istanbul, Turkey. Not only because I live in Istanbul, and have constant encounters with migrants and refugees there, but also since it is the primary urban context of migration in Turkey at the moment.

View from the Istanbul’s “symbolic” Taksim Square, a hub of daily encounters of different populations.

View from the Istanbul’s “symbolic” Taksim Square, a hub of daily encounters of different populations.

Istanbul is estimated to host a population of around 1 million migrants with various nationalities and legal status. The number of registered Syrians in Istanbul reached 563,133 in June 2018, representing 3.75 percent of the total population of the city. Besides the Syrians under temporary protection legal status, there are “short-term resident permit holders” (including refugees who prefer the residence permit over temporary or international protection in order to access increased freedoms, such as living in Istanbul), university students, as well as asylum-seekers (“international protection applicants”, among whom only a tiny number of “people with special needs” are allowed to live in Istanbul; others are obliged to live in a “satellite city” until they may be resettled to a third country; those who are registered in the surrounding areas of Istanbul live and work in Istanbul yet keep travelling back and forth for the signature duty, and some eventually become irregular), and irregular migrants (composed of rejected asylum-seekers, those who overstayed their visas, or those who arrived to Turkey irregularly). In Istanbul, there are migrants from a large variety of countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Somali, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, and other African countries (since irregularity is high, no official data currently exists about different communities living in Istanbul). The main employment sectors are textile, small manufacturing or factory works, construction, street vending, domestic work, sex work, and recycling material collection, among others.

Given this specific context, the question now arises over whether Istanbul is a welcoming host or a ruthless body of interdiction. In my opinion, this is a case which illustrates how the global border regime is implemented within a local context, not only through security mechanisms on the borderline itself but also through the policies and practices beyond, within the multiple layers and complexities of the city.

The main characteristic of the last period has been the hardened regulations and restrictions both for organizations which provide services and support to migrants, and for migrants themselves. In particular since the state of emergency, there have been crackdowns on NGOs and INGOs via statutory decrees or based on the accusation of conducting suspicious or irregular activities, some of whose employees have even been detained or deported. Among other things, contact with migrant groups might be suddenly regarded as a hazardous activity for national security that should be controlled and regulated, and perhaps better monopolized by the state (also concerning the large amount of funding being channelled by various international organizations). With the recently issued executive decrees by Ministry of Education and Ministry of Family and Social Policies (recently transformed into Ministry of Labour, Social Services and Family), activities involving education, psychosocial support and protection of migrant populations have been restricted or confined to the state’s regulations and control. This situation, together with a decreasing flow of funding by donors, has resulted in a shrinking of the amount of civil society support to migrants, which will have the effect of eventually influencing migrants’ access to rights and services, and compelling them to immature and arbitrary state mechanisms.

Registration quagmire

Already the ability to register, which is the first step in access to rights and services, has been severely restricted for different migrant groups in Istanbul. Syrians, who would normally benefit from the “temporary protection” with no conditions, have been refused for registration in Istanbul since January 2018. They had previously been barred in practice due to malfunctioning bureaucracy running on low capacity, but now Istanbul has been declared a “closed city”, except for those who could claim valid grounds (such as family reunification, birth, late-stage pregnancy, or serious diseases which require treatment in Istanbul). For non-Syrian international protection applicants, registration is only possible in designated satellite cities. As a result, the options are either waiting for an unspecified time in a desperate and/or conservative city, or living in Istanbul in exchange of becoming totally irregular yet expecting opportunities from the relatively easy access to the labour market and diversity of host conditions. Finally, even applying for residence permits is not such a viable option for registration, as the procedure has recently been hardened with a long list of documents required at the application. Many applicants have started to receive rejections and been kindly asked to leave the country.

This mechanism of irregularization goes hand in hand with higher securitization and criminalization. Widespread ID controls (i.e. GBT, General Information Scanning) are being conducted at certain public checkpoints like metro stations by police officers, or by mobile teams which address the “usual suspects” of terror or national security regime. Sometimes special police operations target the neighbourhoods that have higher rates of migrant inhabitants, and such operations may take place before or after certain events (such as the crackdown on Syrian beggar families before the Wold Humanitarian Summit, or on the Afghan/Uzbek communities after the night club attack, as well as other terror attacks/bombings in Istanbul), or based on terror allegations.[1]

Detention and Deportation

As a consequence of the widespread controls and criminalization, detention and deportation has been enforced much more efficiently. Up until the fire outbreak and resultant breakout in November 2016, the only detention center in Istanbul was Kumkapı Removal Center in the central Fatih district of Istanbul. The edifice was subsequently closed and turned into a Directorate of Migration Management processing center (now busy with long lines of registration applications), and the detention mechanisms have been efficiently moved to the outskirts of Istanbul. According to official numbers, Silivri detention center has a current capacity of 270 and Binkılıç has 120. When the infamous third airport project will be completed, it will include a detention center with capacity of 700, and a container center with 1200 capacity. All of these sites are located around Istanbul. The numbers of deportations are booming in parallel to the growing detention capacity. One factor which has enabled this is the KHK no.676, which specifies that, under any condition by which a foreigner poses a threat to public health or security, he or she could be deported directly without having the chance to go for appeal. As a result, irregular migrants are being deported in their hundreds and even being returned on “special flights”. A known European practice has finally been imported to Turkey owing to the increased budget allocated for migration management.

A view from the so-called Syrian street at Fatih, right behind Provincial Directorate of Migration Management, Istanbul.

A view from the so-called Syrian street at Fatih, right behind Provincial Directorate of Migration Management, Istanbul.

In addition to this, xenophobia is being fuelled by the deterioration of the local context as a result of the poor economy and increasing feelings of insecurity within society. In response to every simple source of distress within society, such as rising living costs and rents, devaluation of the Turkish lira, or even the overall cleanliness of streets and long lines at the state hospitals, Syrians, or migrants in general are easily pointed at as being responsible. When the Afrin operation prompted strong nationalist propaganda in the media, with stories of martyrs, it was very common to hear complaints such as “why are they not going back to fight in their countries” in different public spaces.[2] The recent election period in the run up to the June 24th snap election was also a specific time of increased anti-migrant discourse. Fear from the nationalist-secular electorate that thousands of Syrians would vote, prompted various politicians during the election campaign to promise to send migrants back home.

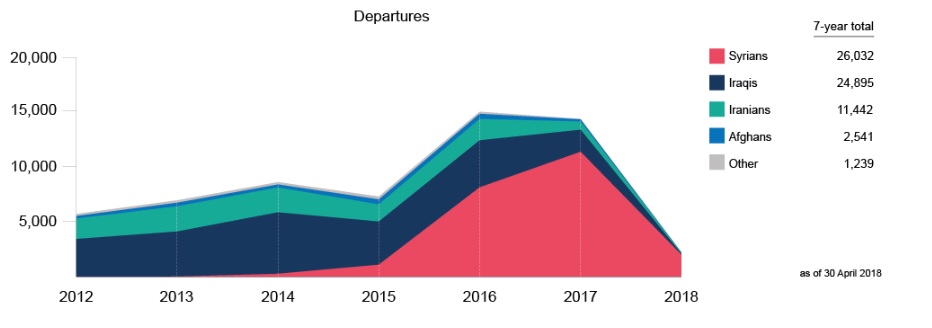

Since no asylum-seekers in Istanbul can enjoy a stable and dignified status, their hopes remain pinned on resettlement, but even the concept itself remains nothing more than a myth. The numbers of completed resettlement cover only a very minor proportion of all the asylum-seekers (according to UNHCR data[3]: 21,686 Syrians were resettled in total between 2014 and 2017, and 2,541 Afghans were resettled in 7 years between 2012 and 2018, despite there being a total of 120,529 Afghan registered asylum seekers in Turkey in the year 2017 alone), and the criteria on which the countries accept the cases are not transparent (although it is believed that certain profiles are favoured according to their education level, religion, sexual orientation and even mental health conditions). In short, let alone Turkey being a safe third country, clear acknowledgement is needed about how it has turned into a functioning regime of detention/deportation, which may even use certain measures to bypass international human rights on asylum and the principle of non-refoulment.

[1] A while ago a rumor spread that following a large scale neighborhood raid organized in Esenyurt, a neighborhood with a Syrian majority in Istanbul, a bus-full of Syrians without valid registration documents in Istanbul were collected and relocated to a border city. This and similar other rumors intimidate irregular migrant groups as well as Syrians without temporary protection IDs, keeping them from visibility in certain public spaces or even pushing them to seek out other places to settle. However, I was recently updated by key members of the Syrian community that this rumour was established to be false. Indeed that such high-security practices or false rumors are mostly put in place to spread a feeling of insecurity among migrants, while playing into the hands of smugglers who have recently started to work between provinces of Turkey, as well as to strategically intimidate European countries by showing them that keeping “threatening” migrant population under control or leaving them to pass is a matter of institutional decision which can be regulated. Another text is required to tackle this opinion.

[2] Recent information – which has not yet been confirmed by official sources – is spreading that certain municipalities in Istanbul are organizing bus travels for Syrians who want to move to Afrin. It is feared that, through the data verification processes that are forcing Temporary protection applicants to re-register in Istanbul, immense data is being collected about Syrians, regarding not only their demographic but also their social and political background. Based on this information, identified families are being called one by one, informed that Afrin is a “safe” place, and invited to move there, even being offered a bus ride by the office of the municipality they are currently residing in. Moreover, I have even heard of cases when Syrians were confiscated of their Temporary Protection IDs when they apply to authorities for travel permission (to another city), on the basis that Northern Syria is a safe place and expecting returnees.

[3] See https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/AfghanRefugeesandAsylumSeekersRegisteredwithUNHCR.pdf, and https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/63880.pdf (where the image below is retrieved).