Reporting from the kritnet conference in Göttingen – Part 2

The HarekAct editorial board attended the 16th kritnet conference in Göttingen between 11-13th of May. It was a very good occasion to share and exchange knowledge, meet our friends, activists and colleagues again and discuss future projects and plans. We took part in the workshop titled “Post 2015 Border Regime – Re-Stabilization of the European Border Regime after the ‘Long Summer of Migration’”. We discussed the extension of borders into the cities following the example of Istanbul; the state of the border regime and public debate on migration in Turkey; and the impact and future of the EU-Turkey statement for both Greece and Turkey. Besides the individual inputs, we had a rich collective discussion with various perspectives, information and experiences brought by activists, researchers and professionals from Germany, Turkey, Greece and Kurdish region, and we are looking forward to keep building on the ideas we had as well as the connections we built there.

Although with a little bit of delay, now we would like to share our contributions to the workshop one by one. Enjoy the inputs presented by HarekAct editors in written and updated form in our blog. Keep posted!

by Lisa Groß

Disobedient Border Crossings…

Since the EU-Turkey Deal, the number of clandestine border crossings has dropped substantially, and the agreement is still deterring many migrants from crossing the Aegean Sea. But that’s not the whole picture: Since April 2016, more than 60.000 people made it across the Aegean, and boats are still landing on the islands on an almost daily basis, despite augmented border control. Recently, the number of migrants arriving on the Greek Aegean islands via the sea are increasing again. While around 3.200 people arrived between April and May 2017, the number almost doubled during the same period in 2018, with circa 6.000 migrants making it safely to Greece. This year up until mid-June, circa 13.000 migrants have crossed from Turkey to Greece, with most of the boats still arriving on Lesvos island (ca. 7.000) (see UNHCR).

In the following text, I will take a closer look at the changes and dynamics in the Aegean Sea following the EU-Turkey Deal. Although border patrol agents are increasing their capacities, we are still witnessing many disobedient border crossings and a civil society which continues to report about rights violations at sea.

…Despite Militarizing and Securitization of the Border

In Action Point 3 of the EU-Turkey agreement struck in March 2016, EU and Turkey agreed that “Turkey will take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU, and will cooperate with neighbouring states as well as the EU to this effect.” With the aim of increasing the capacities of the Turkish border control and preventing more migrants from making the crossing, the EU in cooperation with IOM gave operation trainings to the Turkish Coast Guard, provided 8 high-tech search and rescue (SAR) vessels to the Turkish Coast Guard and intensified cooperation (see HarekAct 2017; HarekAct 2018).

In addition, NATO initiated a mission shortly before the EU-Turkey Deal, still active today, to support “international efforts to cut the lines of human trafficking and illegal migration.” NATO’s role is mainly to collect information, e.g. detecting border crossings through monitoring and surveillance, which they then share with the Greek and Turkish Coast Guard as well as Frontex. As opposed to other border control agencies, they are allowed to operate in both Greek and Turkish territorial waters as well as in international waters (see NATO). Describing their mission as a success, Jens Stoltenberg, NATO general secretary, explained that: “NATO ships have been very often the first spotters of boats and activities, we have shared that information with local coast guards and they have then taken action.”

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, had already been present in the Aegean Sea since 2006 with ‘Operation Poseidon’ with the same aim as NATO, to “stem illegal trafficking and irregular migration through intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance in the Aegean Sea”. In 2015 their budget was tripled and in 2016 they reached an official understanding over cooperation with the NATO mission in the Aegean Sea (see Frontex). Currently, Frontex deploys 12 vessels, 2 helicopters and 739 officers (mainly to support asylum procedures) from Germany, the UK, Croatia and Italy (see borderline-europe).

While the SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) Convention obliges all ships of a certain size and weight to use an ‘automatic identification system’ (AIS), with the purpose of being seen by other ships, this doesn’t apply to warships, thus allowing NATO (and partly Frontex) vessels to maneuver without being visible to others on radar. By sometimes switching off their lights, they are invisible at night, which makes it much easier for them to monitor irregular sea crossings.

Comparing successful border crossings to interceptions by the Turkish Coast Guards

According to statistics by the Turkish Coast Guard Command, so far this year 4.032 migrants have been apprehended by the Turkish Coast Guard, Gendarmerie or National Police along the Aegean coast while preparing to cross to Greece, and another 10.784 have been intercepted at sea and returned to Turkey. Comparing the numbers of successful and failed border crossings, the first thing that draws attention is that both numbers have decreased substantially since 2015. The number of migrants who were intercepted by the Turkish Coast Guard was much higher before the EU-Turkey Deal, and thus before the EU intensified cooperation and further equipped the Turkish Coast Guard, in comparison to the time period after the deal.

| Year | Number of Migrants that successfully crossed to Greece (UNHCR) | Number of Migrants that were intercepted to Turkey | Ratio:

Successful vs. Failed Crossings |

| 2018 | 12.825 | 10.784 | 54% – 46% |

| 2017 | 29.718 | 21.937 | 58% – 42% |

| 2016 | 173.450 | 37.130 | 82% – 18% |

| 2015 | 856.723 | 91.611 | 90% – 10% |

While 90 out of 100 migrants successfully crossed the sea in 2015, this ratio decreased in the following years to 82 percent successful crossings in 2016, 58 percent in 2017, and 54 percent for 2018 so far. The Turkish Coast Guards have prevented more people from crossing but, despite increased militarization and border control, a ratio of more than one in two migrant boats has been successful in reaching their destination. The border regime in the Aegean Sea doesn’t have the capacity to stop these disobedient border crossings when they can’t even stop half of all clandestine boats.

The Civil Counter Corrective

Photographs and reports of continuing arrivals of migrants on the Greek islands and the overextension of the Greek reception system throughout the ‘long summer of migration’ formed a wave of solidarity. Humanitarian activists from all around the globe arrived in Lesvos, Chios and other islands, to support migrants by engaging in Search And Rescue (SAR) operations, boat spotting, shore response, first aid to arriving migrants, relief work and so on. Many of them have stayed and continued their work. Lighthouse Relief, other groups and independent activists are still involved in boat spotting and first aid on several beaches in Lesvos. Currently, Refugee Rescue remains the only civil SAR asset in Lesvos operating in the North of the island. Several organizations such as Proem-Aid, Proactiva Open Arms, Team Humanity and Sea-Watch were engaged in SAR in the past but harassments by the authorities and criminalization campaigns have forced many to leave. The latter came back in 2017 for a ‘Monitoring Mission’, a project that will now be continued by the new association Mare Liberum. These humanitarian and political actors are not only aiming to save lives and make the crossings a little less dangerous, but together with projects like Watch The Med Alarm Phone, they form a civil counter corrective to the militarization of the border, observing and reporting on the operations of the governmental border control actors.

Violence and Rights Violations at Sea

In Greece, since the change in government to SYRIZA/ANEL in 2015, the new migration ministry has tried to put an end to unlawful push backs and violent attacks against migrants at sea, which were previously very common (see e.g. Alarm Phone 2015). Nevertheless, these misconducts have not vanished completely. The Alarm Phone observed a clear occasion of push back (collective expulsion of migrants) in June 2016, and another one in July 2017, where the Hellenic Coast Guard hindered a migrant boat from moving forward by circling the boat and causing high waves, forcing the boat to turn back to Turkey. In another incident in June 2016, Sea-Watch and other civil rescue actors held the Turkish Coast Guards accountable for the deaths of two people, as they started their rescue operation too late .

Despite these, clearly illegal, push backs, there are several other forms of violence and life-threatening behaviors – from pull backs by the Turkish Coast Guards in Greek waters, stabbing or waterboarding rubber boats, stealing or breaking motors to the use of gun violence, as observed by The Intercept. Refugee Rescue reported the use of gun violence by the Turkish Coast Guard to force migrants back to Turkey. Just recently, the non-assistance of the Hellenic Coast Guard in the ‘Agathonisi Case’ caused the death of 16 people at sea.

The Effect of the EU-Turkey Deal on the Situation in the Aegean Sea

With intensified border surveillance, migrants are again being forced to cross in clandestine ways in the dark of the night, having to deal with evermore dangerous crossing conditions. In contrast, during the ‘long summer of migration’ migrants were crossing in plain daylight.

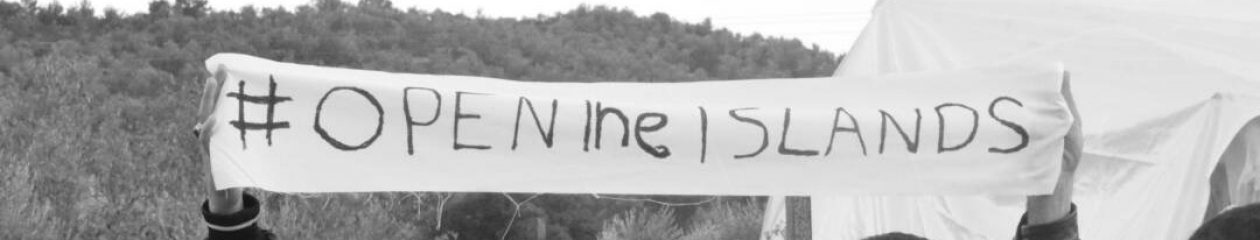

The EU-Turkey Deal has had an immense deterring effect, mainly through the total restriction of movement from the Greek islands, which has created a prison-like situation. In addition, the Turkish Coast Guard, in cooperation with the EU, has increased their capacities in border control. However, the numbers of migrants who are reaching their destinations – the Aegean Islands – is still higher today compared to the number of those who are being intercepted.

While we are still observing many violent incidents against migrants at sea, the levels of violence have not reached the level observed prior to the Greek governmental change in 2015. Despite the backlash of the EU-Turkey Deal, violence against migrants has not escalated further. This can be interpreted as a clear influence of the vital work of the many civil society actors, who in addition to saving lives and assisting people in need, are keeping a critical eye on the operations and behavior of border control actors, in order to report and publicize the horrific incidences where necessary.