Via Hâlâ Gazeteciyiz – This Study by Funda Cantek and Cavidan Soykan traces notions as movement of Turkey-bound migration, the conditions of migrants who have settled in various cities in Turkey temporarily or permanently and their relationship with the local inhabitants, Turkey’s migration policy, and incidents in which migrants were presented as victims or perpetrators by browsing the dailies Sözcü, Hürriyet and Yeni Akit from the beginning of AKP rule in 2002 up to now.

The Turkish version is available here.

Funda Cantek-Cavidan Soykan

Introduction

During its 17-year rule Justice and Development Party (AKP) has established its migration policy on the principle of using migrants as an item for bargaining in domestic and foreign politics despite the changes and variations in the migration policy documents and discourse. In addition, assuming the role of patronage in a geographical region inhabiting mostly Muslim and Turkish populations, and especially for suffering and oppressed peoples living there in violence, poverty and system of exploitation was part of the desire to reap benefits from the outcomes of the civil war in Syria. The migration policy wavered and swerved in line with the course of relations with western and non-western countries yet it continued to instrumentalize consistently the migration process and migrants. Migrants were sometimes embraced with a discourse of protection and brotherhood and sometimes were deemed as a burden, even criminalized. As a result, depending on the changes in the politics, the migrant body was sometimes seen as suffering and oppressed multitudes, as brothers and sisters and sometimes stigmatized as involuntary guests.

The media has always played an important role in the process in which AKP’s migration policy was constructed, popularised and legitimized. These policies, which at first were popularised with the support of the media outlets in favour of the government, became predominant over the years when many domestic media outlets came under the dominance of the government and were purchased by pro-gov investment groups.

This study traces such notions as movement of Turkey-bound migration, the conditions of migrants who have settled in various cities in Turkey temporarily or permanently and their relationship with the local inhabitants, Turkey’s migration policy, and incidents in which migrants were presented as victims or perpetrators by browsing the dailies Sözcü, Hürriyet and Yeni Akit from the beginning of AKP rule in 2002 up to now. One major concern has been to identify the way in which migration processes, migrants and Turkey’s migration policies have been reframed and represented in these dailies. The rationale behind the choice of these three dailies as sample is the fact that each of them appeals to distinctly different readerships. Hürriyet has been for many years a best-selling daily addressing an average and heterogeneous readership. The daily’s editorial policy has differed during different governments to a certain extent and it was sold to a pro-government investment group in the near past; nevertheless, it still remains to be a newspaper that appeals to readers from each segment of society. The daily Sözcü has an editorial policy that adopts the values and arguments of the nationalist left. The content of the news is based predominantly on anti-AKP and pro-Republican values, with People’s Republican Party (CHP) in opposition acting as the primary source of information. From the day it appeared, Yeni Akit has been known to be a supporter of the AKP, following an editorial policy that endorses the changing government policies and working to create public approval for these policies. Though the contents produced by these three different editorial policies and viewpoints may overlap now and then, their attitudes vary in response to the same issues.

While scanning these three dailies, the priority has been given to events, decisions and agreements that have been turning points in Turkey-bound migration movements. Therefore, news contents in certain dates on which publicly influential incidents occurred were analysed.

AKP’s Migration Policies

Conflicts continuing in Syria led to the biggest forced displacement and migration in the world history. Being the neighbouring country most affected by this situation along with Jordan and Lebanon, Turkey harbours 3,611,834 Syrian refugees according to the figures of the General Directorate of Migration Management of the Ministry of Interior (GIGM).[1] Today, 63% of the Syrians who have been forced to flee their country live in Turkey (UN Women, 2018: 65). According to 2017 figures obtained from United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in addition to the Syrians there are 346,800 refugees from various countries who are currently waiting for the result of their application for international protection in Turkey.[2]

Turkey has become the country with highest number of refugees in the world with about a 4-million refugee population since 2014. The housing needs of the Syrian refugees, who entered country as of April 2011, were met partly by means of refugee camps. Adding up to 25, these camps were once criticised on grounds that they were situated close to conflict areas, they were not accessible to he inspection of human rights organizations, the inhabitants of the camps were isolated from the world for long periods which hindered refugees from integrating with the Turkish society and settled life. The camps came to the fore with incidents of maltreatment and sexual abuse targeting children and women despite the fact that they were introduced as ones with high standards by the AKP government. Recently in 2017, the staff in charge of the Nizip camp were judged and found guilty for the abuse of 40 children in the camp between 2104 and 2016, and yet the staff of Disaster and Emergency Management Agency (AFAD) were exempted from judicial process and a decision of non-prosecution was issued, the news of which appeared in the media. [3]

Demographically speaking, about 1 million of the Syrians in Turkey are between the ages of 15 and 24 and 95% of the population live in the cities. Half of the Syrians are registered in four big cities, namely İstanbul, Şanlıurfa, Hatay and Gaziantep in order.[4] According to the report “Needs Assessment of Women and Girls Under Temporary Protection in Turkey” prepared by UN Women and Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Immigrants (ASAM) in 2018, half of the Syrian refugee population is made up of women and girls. The UN Women’s report reveals that the most significant problems for Syrian refugees in Turkey are housing and extreme poverty. Due to language barrier, refugee women suffer from the difficulty in having access to certain rights and services, while at the same time Syrian women and girls are forced by their family members and relatives to early marriages in return for accommodation. These marriages imposed because of extremely poor living conditions also become one of the biggest hurdles preventing women from continuing their education (UN Women, 2018: 62-63).

Housing and poverty concern not only Syrian refugees but also all refugee groups in Turkey. Refugees in Turkey, who have been forced to live in the same city for years without receiving any social and legal assistance with limited freedom of travel and desperately waiting to be settled in another country, are struggling with poverty. Up until the year 2011 when the Syrian refugees began to come to the country, the problems of the refugees living in Turkey did not get much coverage except for those accidents in the Aegean Sea. In these accidents the emphasis was not on the negligence of the government but on the ruthlessness and mercilessness of refugee traffickers who were called human traffickers. Abandoning hope with the asylum system in Turkey, refugees who had to pay large sums of money to traffickers in order to reach West Europe or who had come to Turkey with sole purpose of transferring to Greece were labelled “illegal immigrant” in the headlines only after they lost their lives in these disastrous accidents.

When the issue of immigrants and refugees in Turkey is mentioned, Syrian refugees automatically come to mind. Undoubtedly, the way refugees and foreigners in general are reframed by the media plays a big role in this. Though the information in circulation is produced by political actors, it is the media that provides the presentation and distribution of that information in a specific framework (Helbling, 2004 qtd. in PS: EUROPE, 2017:4). However, refugees who have not applied to GIGM for asylum, or have not registered in any way, whose application for international protection are considered to invalid in different ways or refugees in Turkey who do not want to demand international protection are also part of the refugee population. Here we must mention the fact that within the framework of this study we consider anybody a refugee who demanded sanctuary/asylum and is not granted the status of refugee since their application is still under consideration. The reason for this is that according to the Handbook and Guidelines on 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Legal Status of Refugees, a person is qualified as a refugee on condition that he/she meets the criteria in the Convention (UNHCR, 1992: para. 28).

Though UNHCR records demonstrate a drop in the figures in the last few years, in order to have more accurate data one should in fact also consult the number of migrants who have been stopped and arrested on borders by the military police. Migrants who have been stopped and detained while entering or leaving the country illegally or while travelling without a permit in the country are defined as irregular migrants. Though they are presented as “illegal” and criminalized in the media, irregular migrants are people who have not committed any crimes and may need international protection. They are people who mostly risk their lives by taking recourse to traffickers in order to cross country borders since they do not have passports or visas to the country they wish to travel, which is not a problem for common citizens. The GIGM figures reveal the number of migrants “caught” while trying to cross the border illegally in 2018 to be 251,794. When we look at the countries of origin of these people, we begin to understand why they are called “illegal” too. The countries with highest number of irregular migrants in 2017 were as follows: Syria (50,217), Afghanistan (45,259), Pakistan (30,337) and Iraq (18,488).[5] Before these people’s deportation procedures are activated their protection demands (if any) ought to be considered and they ought to be informed about asylum procedures in Turkey. However, as human rights organizations frequently state, one of the biggest problems in this field in Turkey is that asylum-seekers are prevented from having access to such procedures in formal and informal ways.[6]

The replacement of the word “illegal” by “irregular” both in political documents and the language of the media in Turkey took a long time. The term “irregular migrant” was first used in AKP era legally in Law on Foreigners and International Protection accepted within the framework of alignment with EU acquis. Nevertheless, we cannot say that the criminalizing word “illegal” in the media has disappeared.

Turkey’s Dual Asylum System

Today Turkey has an asylum system dual in structure. The present legal and institutional structure has been established completely in the AKP-government era. The first part of this dual structure is the temporary protection procedure designed for Syrian refugees, which is the first nationality that comes to mind when the word refugee is mentioned; the second part is the international protection (previously called asylum) procedures that were introduced with the adoption of Law on Foreigners and International Protection in 2013. The AKP had declared from the very beginning that it would adopt the open door policy for Syrian refugees. What is meant is a fundamental level protection based on the principle of non-refoulement, which is an essential principle in international migration law. Accordingly, the Syrians who came to Turkey collectively cannot be repatriated to Syria where they would have no life security; however, they cannot apply for international protection individually.

International protection, which is an individual procedure, is applicable only to groups other than the Syrians. Asylum-seekers have the right to apply for one of the three statuses regulated under international protection: the status of “refugee” for which only asylum-seekers coming from Europe can apply, “conditional refugee” status for non-Europeans, for which almost all the asylum-seekers in Turkey can apply and “subsidiary protection” for asylum-seekers outside these two categories, who would face death penalty or maltreatment or personal life-threatening situation in the event of repatriation. As a result, asylum-seekers benefiting from both temporary protection and conditional refugee statuses face an uncertain future since Turkey does not grant any non-European person the status of “refugee” owing to the geographical restriction it preferred while becoming a party to the 1951 Convention.

The Turks’ Perception of Refugees

The AKP government’s migration policy for the Syrian refugees, which differed from other refugee groups, has been shaped directly in tandem with the foreign policy it has adopted. In the first place, the foreign policy pursued when Syria is concerned has never been side-unbiased. From 2011 onwards when the first insurrection against the regime was launched in Syria, the Syrian problem became one of the fundamental components in the search for an ideological hegemony and the restructuring of Kemalist nationalism and national identity project for the AKP. The Syrian policy adopted is a tool in the reshaping of national identity via the Ottoman past and Islam religion. The policy regarding Syria—considered as former Ottoman territory— and the Syrian refugees is closely linked to the AKP’s policy in terms of the domestic politics and especially Kurdish problem (Saraçoğlu, 2018: 19-21).

From the moment the Syrians first arrived in Turkey and were housed in camps, they were treated for a long time as “our Muslim brothers” and “our guests” in line with the AKP’s policy.[7] The expectation that the Syrian regime would soon topple down was voiced by President Erdoğan in 2012: “We will enter Damascus. We will perform our prayer in the Umayyad Mosque, we will embrace our Syrian brothers”.[8] This discourse was continued by the government until October 2014 when Temporary Protection Regulations were accepted. 2015 was the year when the fact that Syrians were not temporary but permanent and they were not guests but refugees gradually began to gain acceptance (UN Women , 2018: 65; Biner & Soykan 2016). During this first four years, while the opposition criticized AKP’s Syrian policy and found faults with this discourse, it also led astray, adopted a populist approach and developed a discriminatory and sometimes even a racist discourse against the Syrians. The opposition, especially Republican People’s Party (CHP), stated that the Syrians would be repatriated at the first possible occasion as if Turkey did not have any obligation arising out of international human rights laws and as if the principle of non-refoulement and the 1951 Convention were not binding for Turkey. And the Syrian refugees, who were exposed to this discourse of two different poles have been subjected to racist attacks due to such fake news as “they receive money from the government”, “they do not pay phone bills” and “they are admitted to university without exam”. This was so much the case that it was influential on healthcare workers serving refugees and doctors were reported to speak discriminatorily of Syrian refugees with whom they found it difficult to communicate due to language barriers (Terzioğlu, 2017). The study “From Information to Perception: Perception of Asylum-Seekers, Migrants and Refugees in Turkey” carried out by the Political and Social Research Institute of Europe (PS: EUROPE) reveals the media’s discriminatory and targeting attitude as well as native population’s discriminatory approach and the hate speech it produces. The study, in reference to Blinder, claims that the media not only encourages the “marginalization” of asylum-seekers, immigrants and refugees but also provides ready justifications for their dehumanization and consequent outcomes (PS:EUROPE, 2017: 4).

The Syrian refugees were being portrayed by the media as “people who ran away from defending their country, cowardly, lazybones doing nothing except for depending on the government allowance, producing offspring copiously and thoughtlessly, disease-spreading, depriving the Turks of their jobs, a culturally backward society ‘compared to Turks’”. Feminist forced migration studies has for long challenged increasingly exacerbating differentiations and binaries such as [good] us and [bad] them between refugees and the host communities in cases of long-term asylum, migration and war. Feminization of migration has been used for the first time in literature to criticise the disregarding of women’s existence and their treatment as dependent on men in migration and migration-related processes (Kofman, 2004). This term does not denote refugee women’s changing status/role only, it is also used to refer to changing gender roles/regimes within the family and labour market that transform themselves with migration. In migration flows men as well women can be coded as passive, unemployed and weak due to lack of work and status. Feminization of men by means of denigratory accusations such as labelling them as draft-dodgers and individuals who are incapable of defending their country is highly common in the Turkish media, especially in the nationalistic discourse (Hyndman&Giles, 2011: 363). Likewise the media depicts refugee children as beggars, ramblers involved in crime, selling paper tissues and sufferers.

In a recent qualitative research by İstanbul Political Research Institute, most of the interviewees commuting by metrobus or living in the vicinity of metrobus lines complained that they feel estranged in their own country due to the increase in the number of refugees/foreigners. When asked their opinion on the solution to living together, half of the participants said that the Syrians ought to go back to their own country with their children (İstanpol, 2018: 7). The research verifies that a clear line of “us and them” has been drawn between two societies and the Syrians, who are defined as foreigners, have been hierarchically placed at a lower level than the Turks (İstanpol, 2018: 20). It would not be incorrect to claim that one of the reasons for these negative attitudes and preconceptions is xenophobia in Turkey. According to “Research on Dimensions of Polarization in Turkey” carried out by Bilgi University Centre for Application and Research in 2017, different party grassroots (AKP, CHP, MHP, HDP and İyi Parti), which are politically polarized in many issues, are observed to have been in agreement in only one issue, namely that the Syrians ought to go back to their country when the war is over.[9] Syrian refugees are seen as a burden especially in terms of economy and the welfare assistance and services they receive in education and health are a source of indignation in society. According to the report “Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Diminishing Urban Tensions” published in 2018 by International Crisis Group, judicial cases and social tension in which the Syrian refugees were involved in the second half of 2017 tripled compared to the same period in 2016; in these incidents at least 35 people, 24 of whom were Syrians, lost their lives. According to the report, the main reasons for the upsurge in the number of incidents were the local people’s conviction that the government prioritized the Syrians in the distribution of social welfare benefits and the authorities’ tendency to hush up the incidents between two societies rather than solve them.[10]

Transformation of Turkey’s Migration Policy in the AKP-Government Era

Turkey switched to a migration policy akin to those of EU countries for the first time during the AKP government. Turkey regulated all the statuses and rights of migrants (foreigners) and asylum-seekers under a single law for the first time with the law prepared between 2010 and 2012 and passed by the Parliament in 2013. Law on Foreigners and International Protection is the first asylum law of the country, functioning at same time as a means for approximation of Turkey’s migration policy with that of the EU. Turkey’s migration policy has been shaped in parallel with the process of adaptation to the EU that started in the early 2000s. The major outcomes of the reorganised migration policy are the new institutional structure organized under the name of Directorate General of Migration Management (GIGM), protection procedure applied for Syrian and asylum seekers of other nationalities, new statuses and related rights, border and deportation policies and legal regulations pertaining to naturalization.

Despite the fact that candidacy for the EU has been a major driving force in the preparation of migration policy especially after 2005, this process had a unilateral and rectilineal progression (Paçacı-Elitok, 2018). Turkey has never been a passive receiver of EU laws and the country’s internal dynamics —social, political and historical— also played a part in the handling of this this process as a mutual bargain. In retrospect, it is not possible to claim that the migration policy adopted since the foundation of the Republic has changed, despite the change in Turkey’s attitude towards the Syrian refugees. Two constituents of this policy, the definition of “migrant” and the people who are eligible for the status of “refugee” (international protection) in this country did not undergo any change with the process of policy transfer that began with the EU candidacy. When the issue of migration is involved, Turkey still sticks, as in the early 20th century, to its reflex to create and maintain a homogenous Turkish identity, which served as a foundation to its process of constructing a nation state, and follows a migration policy, deciding who is to be admitted into the country, “Turkishness” based on Sunnite Islam. Therefore, Turkey did not abolish the geographical restriction it placed in the 1951 Convention on who is to be admitted as refugee into the country though it was one of the terms and conditions of membership. As we mentioned earlier, according to Law on Foreigners and International Protection no one from other than a member country of Council of Europe is granted the status of refugee due to this geographical restriction. Temporary protection could be issued legally in October 2014 and this three-year period proved to be full of uncertainties for both the Turkish and Syrian communities.

The Afghans, Iraqis, Iranians, Somalians and Sudanese, who demanded protection from Turkey just like the Syrians fail to benefit from refugee protection. Both the interim protection granted in Turkey to the Syrians and international protection within the framework of the 1951 Convention are temporary in nature. In other words, unlike other foreigners (migrants), Syrian and non-Syrian refugees benefiting from both of these forms of protections cannot apply for naturalization no matter how long they have lived in Turkey. For this very reason, we may assert that Turkey’s new migration policy has not broken its ties with the past and is still under the influence of nationalism based on ethnicity and religion (Koser-Akcapar; Simsek 2018: 180). When the policy of migration during the AKP-government era is more closely perused, we can still detect a number of major periodizations.

The first period, involving Turkey’s incorporation into EU’s common asylum and migration regime within the framework of EU Harmonization Process, begins in 2002 and continues until 2012; new migration and asylum policy was prepared in this timespan, yet migration and refugees did not appear much on the government’s agenda. In this period, the most significant issue for the EU was prevention of irregular (illegal) migration flow into Greece from Turkey, which had become a transit country on the migration routes, while NGOs in Turkey were trying to make the sea disasters on the Aegean appear on the agenda. For example, in this period, which coincides with the AKP’s first term of government, the issue of migration and migrants did not appear in its election manifesto.[11] The issues of migration and migrants appeared only in reference to the Turkish citizens living abroad and their problems.

The second period, beginning with the entry of the fist Syrian refugees into Turkey, coincides with the government’s brushing aside, in accordance with foreign policy interests, of the previously issued new migration and migrant law and the General Directorate of Migration Management (GIGM), a new institutional structure established in compliance with the ratification of this law. In this period, Prime Ministry and its subordinate body AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Agency) were highlighted as actors, rather than the new law approved in the Parliament in 2013 and the new migration policy tools activated thanks to his law. Influential in this was the inefficiency in the new Directorate, which was still in the phase of being established, as well as the government’s Syrian policy. In the meantime pro-government media presented the Syrians as our fellow Muslims who are in need of the Turkish hospitality so as to generate consent in domestic policy for the sake of counterbalancing the foreign policy adopted then. The biggest “refugee crisis” of all times, thus, ceased to be a part of the problem of migration and refugees and was pragmatically transformed by the AKP into a means of domestic and foreign politics (Danış, 2016: 8). This period continued with Syrians being granted temporary protection in October 2014 and GIGM taking over authority from AFAD concerning the Syrian refugees and came to an end by mid-2015. With the legal regulation of temporary protection, the term “guest” was gradually replaced by refugee.

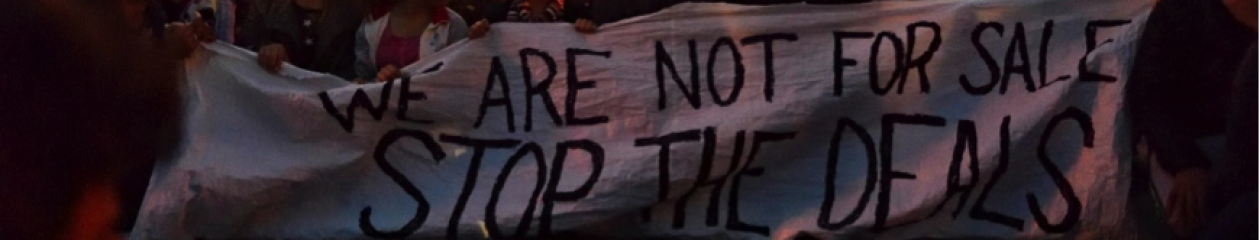

The third period started with “the long summer of migration” in 2015 (Kasparek; Speer, 2015) and was one in which refugees and migration as a whole were used politically as a trump in its fullest sense and turned into a matter of negotiation by the AKP. As of May 2015 Turkey left behind its renowned open policy, albeit not officially. Now Syrian refugee flows could enter Turkey only by means paying traffickers or bribing soldiers. Some Syrian refugees began to desert the camps due to future uncertainties and difficulty of accessing economic and social rights (Biner & Soykan 2016). According to the figures of International Organization for Migration approximately 1 million people entered Europe via Turkey and Greece in 2015 irregularly (IOM 2015). In mid-September a group of 3700 refugees arriving in Munich to apply for asylum in Germany were welcomed with cheers; upon this about 3000 refugees, mostly Syrian and Afghan, marched from Istanbul to Edirne in order to reach the Greek and Bulgarian border.[12] The protest, in which the slogans “Open the Borders! No More Killings in the Aegean Sea! Crossing No More!” were chanted in reference to the boat disasters in the Aegean Sea, came to an end when a representative group of Syrians came together with Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and bureaucrats from GİGM. The government, which accepted the demands of the Syrians and displayed solidarity with the group, thus, gained a political advantage over the EU in the well-known refugee bargain in 2016 (Kaşlı, 2017 qtd. in Ataç et al., 2017:13). An agreement was reached between the EU and Turkey on March 18, 2016 in Brussels with the step taken by German Chancellor Angela Merkel to stop the on-going flow of migrants in the autumn. Thus, Turkey obtained a kind of carte blanche from the EU in return for blocking migrations and detaining Syrian refugees within its borders despite its deteriorating report of domestic human rights and democracy in order to enhance its repressive policy on the dissident groups (Atac et. al, 2017: 14). In fact, this agreement shows a thitherto-unseen facade of the new migration policy prepared within the scope of EU Harmonization Process. The new migration policy that Turkey transferred from the EU was in essence nothing other than the transfer of neoliberal migration control mechanisms such as readmission agreements, expedited asylum procedure, administrative detention and deportation into Turkey as conditions for candidacy under the name of migration management. The goal was the protection of the EU’s outer borders and common domestic market against unwanted forces by means of neighbouring countries (this time against the flow of Syrian refugees). Thus, at the first stage Turkey aspired to complete this mission in return for six billion Euros and visa-free travel for its citizens in the Schengen countries on condition that it meets the necessary requirements. According to this agreement, as of March 20, 2016 all the refugees who entered Greek island by means of irregular ways would be returned to Turkey; in return for every Syrian returned to Turkey a Syrian will be resettled in the EU and Turkey will take every precaution to stop irregular migration to Europe.[13] This mission is an exact indication of the fact that Turkey has undertaken the role of border control against the Syrian refugees for the EU. The scenario was already perfected in January with the introduction of visa obligation for the Syrians coming from the third countries.[14] As part of the agreement, it is not clear whether those who reached Greece in irregular ways and returned to Turkey could access asylum mechanisms if they wished to do so. Turkey, increasing its surveillance capacity to 15,000 people in one go by means of new repatriation centres constructed with EU funds (GİGM 2018), dully performed its guarding position for the EU stronghold by arresting the refugees who attempted to flee. The Syrians were no more “our Muslim brothers” or “our guests”; they are a “migration flow” that needed to be reined back and kept inside Turkey— a “migration flow” not wished to be seen again.

In the fourth period, which began with the 2016 agreement and continued with State of Emergency (SoE) declared in the wake of the failed coup attempt on July 15, Turkey now became an open prison for the refugees. For the Syrians Turkey became a trap with the construction of the wall along the Turkey-Syria border and the strict visa policy. Both precautions closed the door on the new potential refugees. New regulations were devised for work permit to stop irregular migration to the EU and discourage both Syrian and non-Syrian refugees from leaving Turkey in accordance with the EU agreement; however, neither the employment increased, nor the poverty decreased. Because in the face of the difficulty of obtaining work permit, quota application and the enormous informal economy, the employers did not bother to get work permit and took advantage of the refugees who they saw as cheap labour force (Bélanger & Saraçoğlu, 2018).

During the SoE, which was declared on July 20, 2016 and lasted 2 years, critical legal regulations were issued that eliminated basic right and freedoms thanks to decree-laws. One of these was the change in Law on Foreigners and International Protection with decree-law No 676, concerning individuals with deportation decision. With this change undermining the fundamental principle of non-refoulement in the refugee law, Syrian and non Syrian refugees who demanded protection in Turkey could be repatriated to the countries where their lives would be at risk even if they were under the asylum procedures. This change has often been used as a threat by the AKP bureaucrats and politicians especially against the Syrian refugees. Authorities reminded the Syrian refugees that they could be deported any moment in many incidents which began as a judicial case but turned into a lynching campaign against the refugees due to lack of sufficient official precautions and which pitted both communities against each other. In this period the term “refugee” was immediately replaced by “impertinent foreigner”.[15] “The guests” previously claimed to be held in high esteem were easily threatened and deported when necessary![16]

Repressive policies launched against human rights organizations in the SoE period rendered the asylum seekers and Syrian refugees, who could access protection only by means of NGOs, all the more isolated. On the other hand, in early July 2016, just before the coup attempt, President Erdoğan declared for the first time that Syrians would be naturalised.[17] Following this news, which turned out to be highly controversial before the elections, with the amendment made in the related clauses of the Citizenship Law in December the criteria for exceptional naturalization were changed in favour of those investing in Turkey and having large sums of money in Turkish banks and after the unequal implementation of these criteria about 30,000 highly educated professional Syrians were granted Turkish citizenship (Koser – Akcapar; Simsek, 2018: 180).

The SoE period abounded in racist attacks and lynching attempts that broke out in various cities as in the previous summer months and electoral periods. In July 2017, the racist anti-refugee protest in the social media (#We do not want Syrians and #Deport Syrians) ended up with the killing of a nine-month pregnant Syrian woman and her 10-month baby after she was raped by two by her two co-workers. The Ministry of Interior had to make a statement for the first time, disclosing the rate of Syrian involvement in criminal offenses and making a call for peace between Turkish citizens and the “guest” Syrians.[18]

As a result of the wall put up between the Syrian and Iran border and entire blocking of the passage to Greece and Bulgaria by means of barbed wire, the refugees now became a topic for domestic rather than foreign politics. Now Syria was portrayed as a safe country and voluntary returns were encouraged by local authorities following the military operations launched further into Syria. Approximately 3,000 Syrians returned to their country in the summer with bus services provided by the Municipality of Ümraniye in Istanbul.[19] When the refugees lost their value as a trump in the negotiations with the EU and were began to be treated as an economic burden, the camps were gradually closed down. As an election promise President Erdoğan announced for the first time in an election rally in Gaziantep that the camps which previously housed 260,000 of the 4 million refugees would be closed down.[20] According to an exclusive news article in daily Cumhuriyet on November 21, 2018, Ministry of Interior shot down 6 camps for “saving” purposes in 2018. About 31,000 out of 132,990 refugees affected by this decision were settled in other camps; the rest of them were provided with financial aid and left to their own devices just like the others.

Representation of Refugees in the Media

Representation of Migration and Refugees in Turkey Before the Arrival of Syrian Refugees

Until the massive migration flow in 2011, the refugees arriving in Turkey were composed of Iranians, Iraqis, Afghans and Tajiks, who left their countries because of political oppression, punitive practices owing to gender identity and belief or lack of belief and conflicts in their countries and former citizens of the Soviet bloc who came for employment and education. Later followed a mass of refugees suffering from poor and unhealthy living conditions from African countries. In this period refugees could get media coverage only because of such incidents as boat disasters and migrant trafficking. As one of the unchanging principles of journalism, the poor and the citizens of the third world countries would appear in the western media only thanks to such incidents as natural disasters, massacres, stories of violence, war, cannibalism which is in contradiction with the culture and habits of the allegedly civilized world, female circumcision and ritual sacrifice.

Turkey is not exempt from this. News stories dealing with boat disasters are the first of these kinds of incidents. We came to know the term “illegal refugee” thanks to such news. The first major boat disaster in which refugees were victimized took place in 2007 in the Seferihisar district of İzmir. This disaster in which tens of people got killed was covered in the media in a discourse that deidentified and criminalized the refugees. The news in Hürriyet, which related the incident with the headline “Illegal Boat Capsize”, criminalized the refugees by labelling them “illegal.” At first sight the word “illegal” connotes not someone who runs for their life but someone who was on the run since they have been involved in some crime. The news report referred back to the first boat disaster in the 1990s in Turkey and commented on the “illegal refugees who did not learn their lesson.” In addition, the news item did not mention human traffickers who led to the disaster and negligent state authorities; instead the victims were presented as people who did not take lesson form the past incidents and embarked upon an illegal action, all of which was written in a language that did not evoke any sense of empathy or pity in the readers.

The language and style of the news changed from April 2011 onwards with the inflow of masses of Syrian refugees, the change in the AKP government’s migration policy and especially the labelling of the Syrian refuges with the words “brother” and “guest”. The images of the refugees in the news who fled their countries and needed the protection of Turkish citizens contributed to the positive construction of “us” since it demonstrated the Turkish citizens’ hospitality and magnanimity. [21]

The best example of these kinds of news were those that treated Aylan Kürdi, the baby who became the centre of attention in the media all over the world, with his dead body washed ashore after the boat disaster off Bodrum in 2015. Aylan’s dead body that washed up on the beach where tourists went swimming became the symbol of tragedy of migration that affected women and children most. The day after the incident, Hürriyet criticized the callousness of the domestic tourists that went sunbathing on the very spot as if nothing had happened by printing their photos. The daily, answering the reproof that the dead body of baby was printed without blurring, made the following statement that called for pity and empathy for the refugees: “The photo showed the lifeless body of a very young child who wanted to flee war and death with his family and asked for a happy life. Everyone in our news centre who saw the photo felt a harrowing pain, was moved to tears, cursing human traffickers” (02.09.2015).

From “Guests” to “Refugees”

2014 was the year when granting of temporary protection to Syrian refugees was materialized. The word “temporary” is not arbitrary. In this period the term “guest” was replaced by “refugee”. In bureaucracy GIGM took over the authorities of AFAD. Though AFAD was under the strict control of the government and partisan staffing was completed, it failed to produce desired outcomes.

The number of reactionary incidents began to increase in the cities where refugees were densely populated in this period. The sense of tension became so tangible as to get coverage in the media when the refugees who were supposed to lead an isolated life until the day they would go back to their country began to stay longer than expected and stepped out their camps, becoming visible in cities and towns. Gaziantep is one of the cities in which the native population has to live along with the refugees. In July 2014 a crowded group of men, who did not want Syrian refugees in their city, organized a protest through the social media and took to the streets. The daily Sözcü covered the incident as if it were an ordinary protest, ignoring the humanitarian aspect and massive anger that could evolve into lynching. The report was presented with the headline “Protest of ‘We Don’t Want the Syrians’” and the lead referred to “about one thousand people in the city centre who wanted the Syrians to go back to their country.” The news report did not have any information on why these refugees came there and what would happen to them if they went back to their country. What is more, the news claimed that “the Syrians lately have been involved in crimes, creating chaos.” Inclusion of an unspecified crime and chaos is a common practice in all the news that portrays a negative image of refugees (13.07.2014).

In another news story exactly one month later, the tension in Gaziantep was covered in Sözcü with the headline “They went hunting for Syrians at night”. The phrase “hunting for Syrians” in the headline is denigratory and criminalizing. In addition, the daily presents the angry men as victorious hunters and thus encourages lynching attempt. The agitative content in the discourse of the report is also striking: “The main reason for the protest was the rise in rents and increase in unemployment”. This keeps tenants responsible for the rise in rents rather than homeowners and ignores the responsibility of employers in employment problem, thus put all the blame on the Syrians. All this contributes to the presentation of the lynching attempt as a demonstration as if it were a citizenship right and justification of this attempt.

Sözcü, 13.08.2014, “They went hunting for Syrians at night”

In the rest of the news story that fleshed out the background of incident, an allusion was made to a recent incident in Gaziantep’s Ünaldı neighbourhood, where a Syrian tenant stabbed the homeowner to death. This allusion distorts the essence of an individual criminal incident and turns it into a general threat posed by all the Syrians in the city and even in the country. Here we confront the People’s Republican Party (CHP) and its inner circle, which are the daily’s source of reference, on the web page where this news report is published. Among the related links is CHP’s statement, which says “The government is responsible for these incidents” (13.08.2014).

The same incident was also reported by Hürriyet with the headline “Syrian Tension”, which is less agitative compared to the one in Sözcü. Nevertheless, it shows all the Syrians as part of the incident on the basis of the Syrian individual who was involved in this criminal act (13.08.2014). Making generalisations and anonymizations is a common attitude in the media as far as refugees, especially the Syrians, are concerned. When a person of Syrian origin is involved in a crime, tension or illegal activity, the principle of individual criminal responsibility is violated and the crime or misconduct is attributed to the whole refugee population.

Refugees as a means of negotiation

As we indicated earlier, after internal tensions in the Middle East were turned into a war by means of the intervention of international powers, refugees, especially the Syrians have always been treated as a matter of negotiation among the western powers as well as between these powers and the rest of the world. 2016 was the year when these negotiations were carried out most overtly. With the agreement reached between Turkey and Germany, Turkey would receive a financial aid of 3 million Euros first and 6 million Euros later in return for housing the refugees and keeping them away from western countries and Turkey would not be given a hard time for human rights violations on condition that Turkish citizens would be granted freedom of movement in Europe.

In the meantime, Sözcü remained loyal to its anti-AKP editorial line and raised the issue of practices that it thought were in favour of the Syrian refugees in order to criticize the government again and again. After Erdoğan announced that Syrian refugees would be granted Turkish citizenship, the daily covered the issue with the following lead: “President Erdoğan made a new statement about the Syrians, which will create a lot of controversy. He stated that vacant houses owned by TOKİ (Housing Development Administration) might be donated to the Syrians.” From the very start, the report has an agitative introduction since it expressed that this statement will lead to controversies (11.07.2016).

Such arguments as that refugees are here to stay due to the agreement with the West, that the refugees will get their share from national income and that they will even own houses in the country where unemployment and poverty is on the rise reached a level that could easily encourage hostility and offensiveness targeting the refugees. In another news report in the same daily presented as a survey with the headline “10 Syrians make 6 citizens redundant” is an apt example for this hostility solely with its title. The lead of the report based on the data from the World Bank is as follows:

“As the existence of the Syrian refugees in Turkey becomes something more and more permanent every day, the refugees’ impact on macroeconomic stability, notably on growth becomes more visible every day since they constitute more than 3% of the country’s overall population.”

The rest of the news attempts to prove that the rise in the number of refugees led to an increase in inflation based on data. The news report paves the way to the perception that the refugees are an unwanted population since considerable part of their expenses is met by the government and they engender injustice in the distribution of income and welfare level. The unfavourable situations are supported by scientific data to endorse the argument in question and the image created (19.02.2016).

It can be claimed that Sözcü publishes news articles that criminalize and render the refugees suspect, especially the Syrians at every opportunity. The news that appeared after the coup attempt on July 15 with the headline “Citizens in Konya gather in the Mevlana Square” creates the impression that people came together to protest the coup attempt and express a sense of solidarity with the government. However, further in the news report there is a subheading called “Reaction against the Syrians”, which continues as follows: “There were tensions in Konya last night between citizens who gathered after the coup attempt and the Syrian refugees.” The word “tension” is used though the reason for tension is not clarified in the news, which gives the perception that the Syrians living in Konya sided with the coup plotters. The photograph in the news shows a young Syrian being beaten by the local people, which, as a whole, makes the impression that a foreigner is being given a lesson for offending national sentiments rather than being an image of victimization (17.07.2016).

Another example from Sözcü, which tries to create systematic hostility against the refugees, is the news with the title “We’ve spent 36 billion Liras for the Syrians.” The headline uses the first person plural pronoun as if to highlight the fact that the amount spent has been paid by every one of us. The figures have been rephrased as 8 times the amount of the cost of the Third Bridge on the Bosphorus in order to compensate its coldness and incomprehensibility. The general tendency in all news reports except those of economy is to avoid numbers as much as possible and instead refer to a value or figure that correspond to them. In this report, to concretize the size of the loss, the daily uses a corresponding figure, the Third Bridge, which is one of the accomplishments that the AKP is proud of. The photo accompanying the report shows a view of the Third Bridge to accentuate the magnitude of the financial loss (06.08.2016).

Sözcü, 06.08.2016, “We’ve spent 36 billion Liras for the Syrians.”

The pro-gov daily Yeni Akit, on the other hand, assumed the role of appeasing the public reaction against the news that the Syrian refugees will be granted Turkish citizenship. The lead of the news titled “The underlying reason causes of granting Syrians citizenship” in Yeni Akit answers the question “What is Erdoğan’s plan?” The question makes one think that decisions concerning the migration policy are taken solely by the President. In this context, this news also contributes to the efforts of legitimizing the presidential system that the AKP was propagandizing in those days.

Another issue foregrounded in this news report is the advantages that would be garnered by means of naturalizing the Syrians. The report does its best to convince the reader about the advantages that this move would bring in terms of fight against DAESH (just like the government, the daily too opts for this Arabic acronym for ISIS, Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, which also reveals its ideological position) and US-Turkey relations. It is obvious that Yeni Akit seeks to endorse and legitimize the government’s move to enable Syrian refugees to remain in Turkey permanently at a time when the incidents of anger, hostility and aggression against them are on the rise (05.07.2016).

Compared to Sözcü and Yeni Akit, the daily Hürriyet approached the issue from the viewpoint of human rights. The news report with the headline “7 Thousand Syrians are to be naturalized” by Nuray Babacan seems potentially conducive to indignation at first sight; however, in the lead the refugees are described as “about 3 million Syrians who came to Turkey after the war in Syria”. Here the reason why refugees are is explained not with the word “flee” (which has negative connotations) or “take shelter” (which makes them look incapable and helpless); instead the report adopts a relatively objective attitude that succinctly implies that asylum-seeking is a human right. News stories that appear with the name of the reporter can carry the traces of objective perspectives and backgrounds of experienced journalists (08.07.2017).

The number of xenophobic attacks especially against Syrian refugees increased along with those perpetrated against NGOs protecting refugee rights of the Syrian refugees throughout the year 2017. Dissident media too made provocative news that could contribute to such hostile acts such as Sözcü’s news titled “The Syrians rent shops in Osmanbey”. The headline, which sounds like a crime report, highlights a transition from the of image of poor, victimized and oppressed Syrian refugee to that of a powerful and well-off tradesman who is so rich as to rent a shop in Osmanbey, one of the most prestigious and wealthiest districts of Istanbul.

The web version of the daily has an embedded link titled “Every 10 Syrians make 6 Turks redundant”, which confirms the print version. The news in the link states that the local tradespeople are annoyed by the Syrians who rented shops in Osmanbey, “Owing to the fact that their work ethics do not overlap in terms of employing illegal Syrian workers and unfair competition.” When a helpless asylum-seeker attains a status high enough to compete with the local population of the country where he sought sanctuary is almost like the declaration of the fact that he is no more a victim. This naturally makes him liable for hostility and attacks (17.05.2017).

Hürriyet covered the relations between refugees and the local people along with field notes and interviews during the process of assigning of AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Agency) to implement the migrant policies in 2013. The daily frequently revealed the sense of discontent among local people in cities such as Urfa, where refugee camps are situated. The interview with the headline “Do we have to become Syrian to get treatment?” relates the complaints of the locals, who think the Syrians are better off than themselves in terms of healthcare services and employment (22.07.2013). What is striking in the interview is that the local people direct their aggressive and discriminatory discourse against the refugees rather than criticizing the authorities and employers that allegedly favour refugees. In the same year Hürriyet featured a news article with the provoking title “Syrian voters alarm”, based on an allegation by CHP MP Birgül Ayman Güler. It is claimed that under the auspices of the AKP Syrian refugees will be inserted into the voter lists and that they will vote for the AKP. The allegation still being investigated by the CHP headquarters has been presented with a heading that suggests as if the claim have been confirmed (14.10.2013).

The individual offenders in criminal incidents in which Syrian refugees are involved are identified wholesale as “Syrian refugees”. Thus, a negative image created by one or few individuals involved in a crime is attributed to the whole refugee community. Featuring a neighbourhood fight among youths in Sivas, the report in Sözcü displays such an attitude by saying “A tension ensued between Syrian refugees and the local residents when a Syrian family disturbed their neighbours and beat a 15-year-old child.” One party is designated as the whole refugee community while the other is defined as the local residents, that is, the real owners of that region. According to the information received from the group designated as the local residents, the Syrians crammed tens of people into the house they rented for a couple of people and exhibited immoral behaviour, wearing improper clothes and harassing women. Such vague, moralistic and at the same time agitative terms such as immoral and improper are functional in criminalizing the targeted group (24.08.2017).

Unlike these news reports that teem with hate speech, the news report covering the case of the pregnant Emani Al Rahmun, who was murdered along with her little child after she was raped in the Kaynarca district of Sakarya in 2017, comply better with ethical criteria in terms of language and discourse. Nevertheless, it can be claimed that this aggression has been introduced as ordinary male aggression in the news that appeared in these three dailies. It is obvious that xenophobia and, as an extension of it, media contents that legitimize the attacks against minorities and defenceless aliens have a significant role in paving the way to these acts of violence. Even in this news report, the motive for this act of violence is given as the rivalry between Al Ramun’s husband and the two male murderers. The victim Emani Al Rahmun introduced as “the 9-month pregnant wife of Halid Al Rahmun, who fled the war in Syria.” The murderers, however, are specified as “the neighbours of Halid Al Rahmun, Emani’s husband.” In both statements the woman is rendered a passive the extension of the paterfamilias, which shows the traces of a sexist attitude. As mentioned in our discussion of the feminization of migration, women and children become the victims of conflicts created by men and suffer most from the traumas of migration practices in which they do not have a say. Emani Al Rahmun and her children too are such victims. However, in the news they are presented simply as individuals who are part of the family in the possession of the paterfamilias and as victims of brutal male violence (01.12.2017).

At this point, it is necessary to dwell on the way refugee families in general and women and children refugees in particular appear in the media. The pro-govYeni Akit and the pro-opposition daily Sözcü as well as Hürriyet stress indirectly the fact that refugees are different from the native population in terms of culture, life style, family ties and social relationships even though they belong to the same religion and even the same sect as the native population. This difference implies a gap in terms of civilization and level of welfare to the favour of the native population. Objectively speaking, refugees who have had to flee their homes because of war and death with just a handful of belongings and reached a destination by means of illegal or long and arduous ways and some of whom were struggling with poverty in their home country are expected to be in destitute in many respects. The traces of this destitute are visible on their bodies too. The media provides us with images of refugees who are usually shabbily dressed, worn out, anxious and poor in the news concerning them. These images may move one’s feelings of compassion while at the same time may lead to disgust and condescension. The refugees who are implicitly or explicitly presented along with such images in the news as people “who have been dragged into a backward and barbarian ethnic or sectarian conflict” or someone from a country where people are oppressed due to their identities makes the reader feel that s/he is part of the western civilization, living in a relatively prosperous, stable country. This is plausible since the Turks are the hosts, while those who ask for their protection to save their lives are the refugees. Thus, encounters with the refugees immediately engender a hierarchy in which the citizens of the host country are placed on the highest rungs in the ladder of civilization.

In the news we see that refugee women, as we have seen in the case of Emani Al Rahmun, are mostly dragged along by a paterfamilias (father, husband, brother or another powerful male in the family), who decides to migrate on his own, and set off for a destination decided again by him alone. As we have dwelt in the section on the feminization of migration, this is, to a great extent, the case. However, women’s victimization and secondary positions in the process of migration are reproduced in the news contents. Especially in the families migrating from the Middle East men are presented as almost without exception polygamous, women as victims of male violence and families as multi-child ones.

Sözcü, 10.03.2018, “The Real Syrian Problem in Turkey”

3,540, 648: The number of Syrians in Turkey

234,529: The number of Syrians hosted in 21 camps

3,306,119: The number of Syrians living in 81 cities

İstanbul, Hatay, Gaziantep: The cities with highest number of Syrians

311,000: The number of Syrian children who were born in Turkey

1,460,000: The number of inpatient Syrians treated in hospitals

19,020: The number of Syrians who received work permit

30 billion dollars: The sum spent for the Syrians up to now

1,214,000: The number of Syrians who had operations in hospitals

55,583: The number of Syrians naturalized

25,000: The number of Syrians naturalized aged 0-18

The visual above appeared along with a news report based on a study focusing on the data concerning the Syrian refugees in Turkey. The family seen here in the visual is a Syrian family composed of a middle-aged man, three relatively younger women and many children. This family, representing the Syrians who made entry to Turkey, also brings to mind poverty which is common in non-western countries, polygyny which is characterized as a sign of backwardness, child brides and overpopulation.

The news that appeared in Hürriyet (“Do not anger your husband lest he gets a new woman from Syria”) reminds the fact that polygyny that already exists in Turkey gains currency again with the coming of the Syrians (08.03.2011). Polygyny, which Syrian women took recourse to or are forced to so as to live freely in Turkey, secure themselves and their families by obtaining Turkish citizenship, has certain similarities with the experiences of women who migrated to Turkey from the Soviet Union countries in the post Cold War period. Polygyny, which used to create a lot of social unrest in those times too, is being treated critically today in the anti-AKP media outlets since a second marriage with a foreign woman can lead to the disintegration of families and victimization of the first wife. Printing a news report on this issue, Hürriyet violates the principle of objectivity by conveying the words of the Mayor of Nusaybin without quotation marks. In addition, the daily’s headline seems to be threatening the female readers or asking them to act submissively. However, it turns out in the rest of the news that these words, in fact, have been uttered by the Mayor in order to criticise the threat of polygyny that forces women into obedience and submission.

The news report in the pro-gov daily Yeni Akit titled “Syrian refugees return home for good” is accompanied by a photograph of a burqa-clad refugee woman whose eyes are visible only. This beautiful eyed woman staring at the camera is Yeni Akit’s representation of Syrian refugees. What the daily does here is to gender the refugee and while doing this presents it orientalistically in the image of a displaced, poor yet attractive woman who takes shelter under the protection of a powerful person.

Yeni Akit, 03.09.2018, “Syrian refugees return home for good”

In 2018, the Syrians seemed to be left to their own devices because they no more served as material for domestic politics. After President Erdoğan himself announced that the camps would be closed down, sensational news concerning the problems caused by the refugees began to appear in the media. Syrian refugee crisis was once more turned into a political issue. Sözcü ranges as the daily that produces the most damaging news about the Syrians because this is one of the feasible ways of criticising the government. One of the most striking examples of these news reports is the one with the headline “The Syrian Canton … The Turks flee!” The Syrians, who are foregrounded as a people who fled their country years ago and came to Turkey and whose victimization ought to move feelings of compassion, are turned into a well-off community who drive away the native Turkish populations from their comfortable living quarters: “About 30,000 refugees began to form small cantons in the centre of Samsun. The Turks have evacuated the area. The refugees, who are mostly Syrians, started their own businesses, and have a private clinic of their own.” The news report also states that the flats left behind by the people who deserted the area are rented immediately by the Syrians. The report, which presents the Syrians as invaders, tries also to give the impression that the Syrians have formed cantons. This vague piece of information, which is reminiscent of PKK’s demands for self-rule, introduces the Syrians as if they were a population that demanded land from Turkey, founded a autonomous Syrian Republic after their demand has been met and drove the native Turks away (01.11.2018).

Sözcü, 01.11.2018, “The Syrian Canton”

The report in Yeni Akit titled “Syrian refugees return home for good” claims that refugees in Turkey have begun to move back to their own country thanks to the success of the Afrin and Zeytin Dalı (Olive Branch) operations. The report also includes interviews with the Syrians who express their gratitude to President Erdoğan for enabling them to return their country (09.10.2018). After this report, which has the overtones of wonderful blessings, another report was printed in Yeni Akit that served to get rid of the disillusionment emerged when the expected remigration did not come true. The daily, sticking to its pro-gov editorial line, talked about the benefits that could be reaped in the foreign policy from the Syrians still hosted in Turkey. The report titled “Greece in panic! Turkey opens its doors to the refugees” introduces Greece, Turkey’s primeval enemy in the narrative of official history, as a country in distress owing to Turkey’s move. The exclamation mark in the title foregrounds the panic Greece is claimed to be suffering from. The report highlights the fact that hosting refugees cements relations with friendly nations and provides advantages over enemies (08.10.2018).

Mehtap Yılmaz, Yeni Akit columnist, recalls the image of “the Syrian who sneaks away from his/her country”, which has been one of the arguments since the beginning of the migration flow, in her agitative article called “Why should the Syrian refugees make merry while the Turkish soldiers fight?” In the pro-gov Yeni Akit a change can be observed in parallel with the change in the government’s discourse and market fluctuations and accordingly victimized brothers are morphed ths time into a community of cowardly, reckless traitors (09.02.2018).

On the other hand, a black propaganda is sustained against NGOs and international organizations working for refugee rights. Likewise, based on the missionary activities of Pastor Brunson, who had been detained for a long time in prison on the charge that he was involved in the failed coup attempt, it is claimed that similar activities are backed by the UN, which allegedly gains advantage from refugee associations (24.09.2018). In another news article United Nations High Commission for Refugees is claimed to “have turned a blind eye to refugees” so as to defame its financial support for LGBTIs. Likewise, refugees are referred to as people “who sought sanctuary in Turkey to protect their chastity/honour” again and separately in order to denigrate the High Commission and LGBTI communities. Here, the main objective is not to announce the fact that refugees have been deprived of the international support but to defame a community, which is at variance with the AKP’s sense of decency and does not belong to its followers, and an international organization that supports the dissident movements in Turkey.

Conclusion

An overall review of the way refugees is handled in the media during the AKP era suggests that the word refugee is synonymous mainly with the Syrians. In the discourse employed while referring to refugees, the image of guests and brothers has been replaced by that of unwanted, menacing aliens, asylum-seekers who appropriate the rights of the native population.

Refugees were at first mentioned in connection with boat disasters and migrant traffickers and presented as victims; however, as they began leave their camps and mix up with the locals and got rid of the idea of temporary sojourn, they began to be seen in the public and presented in the media as disruptive political subjects, a nuisance in every facet of daily life, a mass of people destroying the order of the locals in employment and healthcare, unbalancing the existing level of welfare and becoming another party to the income sharing. Refugees, considered as a people outside the western civilization due their culture, beliefs and social relations, have been reframed with these characteristics in the media texts and the visuals that accompany them.

Refugees are presented in the anti-AKP media as a mass of delinquent, disease-spreading people, antagonistic to the public order and instrumentalized by the AKP for the perpetuation its rule. Interestingly, they have been considered as a material to exhibit the government’s strength, bargaining power and protectionism in the pro-AKP media. The major problem concerning the representation of refugees in the media is twofold: first, there is the failure to comprehend that being a refugee is a human right; and second, the media concentrates on the problems arising out of migrant masses without considering the causes and tragic consequences of migration. Their political instrumentalization without their consent, the failure in meeting their basic human needs, not getting an affirmative response from Turkey or other countries to their demands for protection and having to lead a heimatlos life without an identity, waiting for an uncertain future… these are the issues that get a rather scanty coverage in the media.

References

Atac, I., Heck, G., Hess, S., Kaşlı, Z., Ratfisch, P., Soykan, C., Yılmaz, B. (2017) ‘C/ontested Borders, Turkey’s Changing Migration Regime, Editorial Introduction’ içinde Movements, 3(2): Turkey’s Changing Migration Regime and Its Global and Regional Dynamics, Transcript Publishing: 9-23.

Bélanger, D. & Saracoglu, C (2018) ‘The governance of Syrian refugees in Turkey: The state-capital nexus and its discontents’, Mediterranean Politics, DOI: 10.1080/13629395.2018.1549785

Biner, Ö. & Soykan, C. (2016) Suriyeli Mültecilerin Perspektifinden Türkiye’de Yaşam Mülteci-der Raporu, 18 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://www.multeci.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/SURIYELI-MULTECILERIN-PERSPEKTIFINDEN-TURKIYE-DE-YASAM.pdf adresinden erişildi.

BM Kadın Birimi (2018) Türkiye’de Geçici Koruma Altındaki Suriyeli Kadın ve Kız Çocuklarının Ihtiyaç Analizi Raporu, 1 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://www2.unwomen.org//media/field%20office%20eca/attachments/publications/country/turkey/the%20needs%20assessmenttrwebcompressed.pdf?la=en&vs=3220 adresinden erişildi.

Danış, D. (2016) ‘Türk Göç Politikasında Yeni Bir Devir: Bir Dış Politika Enstrümanı Olarak Suriyeli Mülteciler’ içinde Genç, F (ed), Helsinki Yurttaşlar Derneği Saha Dergisi Sayı 2:6-12.

Doğanay Ü ve Çoban Keneş H (2016)., “Yazılı Basında Suriyeli ‘Mülteciler’: Ayrımcı 177 Söylemlerin Rasyonel ve Duygusal Gerekçelerinin İnşası”, Mülkiye Dergisi, 40 (1), 143-184.

Erdoğan, E. & Uyan-Semerci, P. (2018) Fanusta Diyaloglar: Türkiye’de Kutuplaşmanın Boyutları, araştırma sunuşu, Göç Çalışmaları Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi raporu 10 Aralık 2018 tarihinde https://goc.bilgi.edu.tr/media/uploads/2018/02/05/bilgi-goc-merkezi-kutuplasmanin-boyutlari-2017-sunum.pdf adresinden erişildi.

International Organization for Migration IOM (2015) Mixed Migration Flows in the Mediterranean and Beyond. Compilation of Available Data and Information. Report-ing Period 2015. 10 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://doe.iom.int/docs/Flows%20Compilation%202015%20Overview.pdf adresinden erişildi.

İstanpol (2018) Bir Algı Araştırması: İstanbul Yolculuğunda Suriyeli Hayalet Çocuklar, İstanbul Politik Araştırmalar Enstitüsü Raporu, 21 Aralık 2018 tarihinde https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/c80586_820773b2affc4b3c83b279e95d035b81.pdf adresinden erişildi.

Hyndman, J. & Giles, W. (2011) ‘Waiting for what? The feminization of

asylum in protracted situations’, Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of

Feminist Geography, Vol. 18, No. 3, June 2011, 361–379.

Kasparek, B. & Speer, M. (2015) ‘Of hope, Hungary and The Long Summer of Migration’ 15 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://

bordermonitoring.eu/ungarn/2015/09/of-hope-en/ adresinden erişildi.

Kofman, E. (2004) ‘Global Gendered Migrations’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 6:4 December 2004, 643–665.

Koser-Akcapar, S. &Simsek, D. (2018) ‘The Politics of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: A Question of Inclusion and Exclusion through Citizenship’, Social Inclusion, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 176–187.

Uluslararası Kriz Grubu (2018) Türkiye’deki Suriyeli Mülteciler:

Kentsel Gerilimleri Azaltmak, Avrupa Raporu N°248, 10 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://www.raporlar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/248-turkey-s-syrian-refugees-turkish.pdf adresinden erişildi.

UNHCR (1992) The Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status under the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol relating to the Refugees 10 Aralık 2018 tarihinde https://www.unhcr.org/4d93528a9.pdf adresinden erişildi.

UNHCR September 2018 Fact sheet 11 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Turkey%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20September%202018.pdf adresinden erişildi.

UNHCR Country Profile11 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/2544?y=2017#year adresinden erişildi.

Paçacı – Elitok, S. (2018) Turkey’s Migration Policy Revisited: (Dis)Continuities and Peculiarities, Instituto Affari Internazionali Report, 10 Aralık 2018 tarihinde https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/turkeys-migration-policy-revisited-discontinuities-and-peculiarities adresinden erişildi.

PS: EUROPE (2017) Bilgiden Algıya: Türkiye’deki Sığınmacı, Göçmen ve Mülteci Algısı Üzerine Bir Çalışma, Avrupa Siyasal ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Enstitüsü Raporu, 21 Aralık 2018 tarihinde http://pseurope.org/tr/wpcontent/uploads/2017/07/T%C3%BCrkiyedekiS%C4%B1%C4%9F%C4%B1nmac%C4%B1-G%C3%B6%C3%A7men-ve-M%C3%BClteciAlg%C4%B1s%C4%B1-%C3%9Czerine-Bir%C3%87al%C4%B1%C5%9Fma.pdf adresinden erişildi.

Saracoglu, C (2018) ‘The Syrian Conflict and the Crisis of Islamist Nationalism in Turkey’, Turkısh Policy Quarterly, Volume 16 Number 4: 17-26.

Soykan, C. (2017) ‘Access to International Protection – Border Issues in Turkey’ içinde O’Sullivan, M. &Stevens, D. (ed) States, the Law and Access to Refugee Protection Fortresses and Fairness, Hart Publishing: 69-91.

Terzioğlu, A. (2017) ‘The banality of evil and the normalization of the discriminatory discourses against Syrians in Turkey’, Anthropology of the Contemporary Middle East and Central Eurasia 4(2): 34–47.

Daily News reports

Hürriyet

13.08.2014

02.09.2015

08.07.2017

08.03.2011

Sözcü

13.07.2014

13.08.2014

11.07.2016

19.02.2016

06.08.2016

17.05.2017

01.12.2017

10.03.2018

01.11.2018

Yeni Akit

05.07.2016

03.09.2018

09.10.2018

08.10.2018

09.02.2018

24.09.2018

- The figures of GIGM as of December 6, 2018. See: http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/gecici-koruma_363_378_4713_icerik (Date of access: December 11, 2018). ↑

- For UNHCR figures see, see http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/2544?y=2017#year (Date of access: 11 December 2018). ↑

- See http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/afad-kampinda-iki-yilda-40-cocuk-istismari-40387923 (December 6, 2018). ↑

- UNHCR September 2018 Fact Sheet, see http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Turkey%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20September%202018.pdf (Date of access: December 11, 2018). ↑

- See http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik3/duzensiz-goc_363_378_4710 (Date of access: 9 Aralia 2018).). ↑

- For a detailed analysis on this issue see Soykan, C. (2017) ‘Access to International Protection – Border Issues in Turkey’ in O’Sullivan, M. &Stevens, D. (ed) States, the Law and Access to Refugee Protection Fortresses and Fairness, Hart Publishing: 69-91. ↑

- A retrospective look at AFAD’s internet page as far as 2011 will give enough evidence for the repercussions of this attitude in official documents and bureaucracy. For an example from 2014 see https://www.afad.gov.tr/tr/1681/Turkiyenin-Ortak-Vicdani-Misafirleri-Kucakliyor (Date of access: December 8, 2018). ↑

- http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/erdogandan-onemli-mesajlar-21386210 (Date of access: December 11, 2018). ↑

- See slide no. 65: https://goc.bilgi.edu.tr/media/uploads/2018/02/05/bilgi-goc-merkezi-kutuplasmanin-boyutlari-2017-sunum.pdf (Date of access: 10 December 2018). ↑

- See https://www.crisisgroup.org/tr/europe-central-asia/western-europemediterranean/turkey/248-turkeys-syrian-refugees-defusing-metropolitan-tensions (Date of access: December 13, 2018). ↑

- See https://acikerisim.tbmm.gov.tr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11543/954/200304063.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Date of access: December 13, 2018). ↑

- For general information and the demands of the demonstrators see http://gocmendayanisma.org/2015/09/20/crossing-no-more-basin-aciklamasinin-turkcesi/ (Date of access: December 14i 2018) ↑

- See http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-16-963_en.htm (Date of access: December 14, 2018). ↑

- See https://www.dw.com/tr/t%C3%BCrkiye-vize-uygulamas%C4%B1na-ge%C3%A7iyor/a-18965827 (Date of access: December 14, 2018) ↑

- See https://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/basbakandan-suriyelilere-uyari-suc-isleyen-disarida-kalir,8hNDlOQfnU2PAtIqkkWBFw (Date of access: December 14, 2018). ↑

- The British daily Guardian prepared an extensive news report on this issue, while no news appeared in the Turkish press concerning this incident. See https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/oct/16/syrian-refugees-deported-from-turkey-back-to-war (Date of access: December 14, 2018). ↑

- http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-suriyelilere-vatandaslik-imkani-verecegiz-37304608 (Date of access: December 15, 2018). ↑

- See https://tr.sputniknews.com/turkiye/201707051029138269-icisleri-bakanligi-suriyeliler-turkiye-suc-orani/ (Date of access: December 15, 2018). ↑

- See http://www.milliyet.com.tr/42-suriyeli-daha-esenyurt-tan-ulkelerine-istanbul-yerelhaber-2987384/ (Date of access: December 15, 2018). ↑

- See http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/5-multeci-kampi-kapatilacak-suriyeliler-sinira-40915006 (Date of access: December 1, 2018). ↑

- Doğanay Ü ve Çoban Keneş H (2016)., “Yazılı Basında Syrian ‘Refugees’: Ayrımcı 177 Söylemlerin Rasyonel ve Duygusal Gerekçelerinin İnşası”, Mülkiye Dergisi, 40 (1), 143-184. ↑

This study was originally published by Hâlâ Gazeteciyiz.