Written by Sadek Abdul Rahman

Translated by Ahmed elGhamrawi

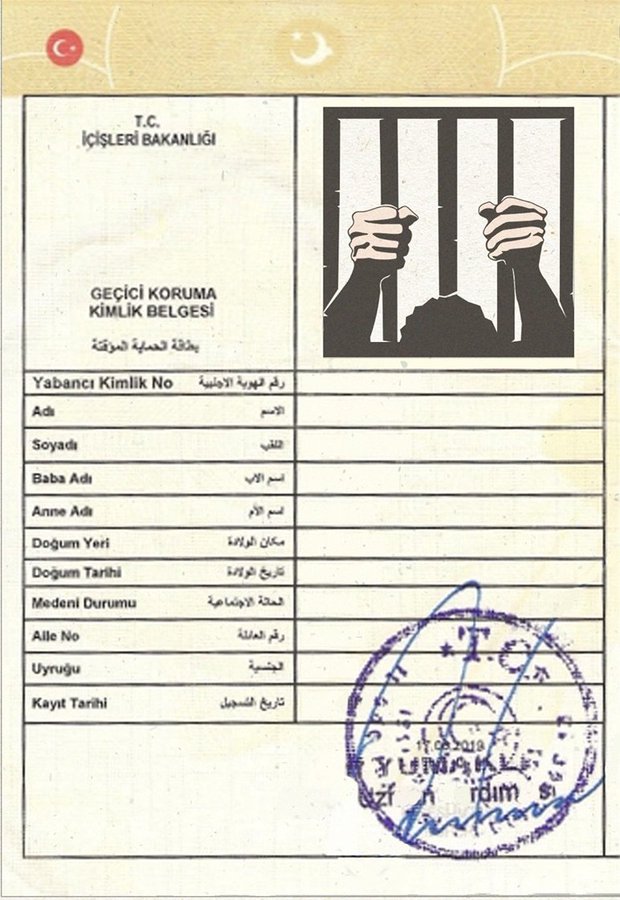

Hundreds of thousands of Syrians are currently living under siege in Turkey, particularly in Istanbul. Using the term “siege” is no exaggeration here – many don’t dare step out of their homes to secure their basic needs. They cannot go to work, and they can’t even leave their homes in order to try and correct their legal situation, according to the demands of the Turkish government. Even in their homes, tens of thousands of Syrians don’t feel safe. It is reported that Turkish police patrols have entered homes in Istanbul and Gaziantep, arresting anyone without a Temporary Protection ID, and even those who have Temporary Protection IDs but registered in different provinces.

The fear overwhelming Syrians in Turkey today is compounded and multi-layered. Just as resources are distributed unequally in this world, the level of fear amongst Syrians varies with their legal and economic situation. Nevertheless, all are scared, and their fear is a complex tale that could seem hard to explain.

As reported by the Turkish government, there are up to 3.5 million Syrians who hold temporary protection IDs in Turkey. The government provides them with healthcare services and allows their children to register in Turkish schools free of charge. A small percentage of these are getting limited financial aid from the EU, which is channeled through the Turkish Red Crescent, and is exclusively for families exceeding five members, the disabled and the chronically ill. The remaining majority of millions of Syrians must rely on work to earn a living for themselves and their families. Having a temporary protection ID does not entitle its bearer to a work permit. On the contrary, one still needs to apply for it, and meet its exceptionally difficult requirements. It is sufficient to know that the total number of Syrians who had acquired a work permit was only 32,000 up until the end of 2018.

In addition to those covered by Temporary Protection, there are less than 100,000 Syrians living in Turkey with short term residency permits, and an unknown number of unregistered people who are also working in Turkey to earn their living with no legal work permits. Many of those registered in small provinces have been forced to move to bigger cities, particularly Istanbul, in order to find employment opportunities. This has pushed them into situations which violate two obligations: not residing in their province of registration, and working without a work permit. We can now have an understanding of the work conditions that a major part of Syrians have to live with in Turkey – working without legal permits, subjected to the worst forms of exploitation, long working hours, salaries well below the national minimum wage, without health insurance, social security and no hopes of a retirement fund.

All these people – who constitute the majority of Syrians in Turkey – are thus being treated as criminal “violators” from a legal perspective for not having a work permit, while they are the real victims of abuse and exploitation. They are subject to the threat of detention and deportation at any time, and with the tightened security in their lives, many have found themselves without work, and with no source of income for themselves and their families.

It is always easier to assign blame to the disadvantaged, the refugees themselves, for their own miserable conditions. But the responsibility here lies, no doubt, with the Turkish authorities. They have not taken any serious steps to legalize the stay of Syrians, and still insist on invoking the term “guests” when addressing refugees, instead of acknowledging their status as refugees with clear and well-defined rights. The responsibility also lies heavily with Turkish capitalists. They have found a golden opportunity to exploit Syrians for more profits, employing them without legal contracts, work permits or any obligation to pay at least the minimum wage. We can now understand how at least a million Syrians have come to live in Turkey on less than the minimum wage, and the additional billions in profits made by capitalists in Turkey. Billions saved by hiring and abusing Syrian labor, instead of legally employing Turkish nationals and incurring losses in legal minimum wage work contracts, social security, insurance costs, etc.

Prior to the new regulations in Turkey, Syrians were already living with daily insecurity. Jobs for Syrians are insecure, they have no future potential, and they don’t even qualify them for citizenship. The number of those who have taken Turkish citizenship, according to the Turkish Minister of Interior is 92,000, less than two percent of Syrians in Turkey. The fear has grown to massive proportions, as they now find themselves under the threat of forced deportation to Syria, where they could very well lose their lives.

Turkish authorities claim their latest campaign of carefully scrutinizing the documents of migrants and refugees, and detaining and deporting some, only targets “violators”. The violators are meant here as those working without a work permit, those living in Istanbul while registered in other provinces, and surely those who are not yet registered. Authorities also say that no one will be forcefully deported to Syria, but will be transferred instead to their registration provinces, or to other provinces with open registration.

Even if the Turkish government sticks to the declared decisions, it is still scary for many. These decisions clearly violate the basic human rights of freedom of movement, of choosing where to live and work, and threatens many families composed of members registered in different provinces with forced separation. What makes the fear inclusive of everybody is that the Turkish police are not going by the book in enforcing the declared decisions. They have detained tens of Syrians, arrested on the streets, metro stations, workplaces and even from inside homes, and deported them back to Syria after forcing them to sign a “voluntary repatriation” document, which simply means they are going back to Syria willingly.

This is made even more alarming by the Turkish government’s repeated denials that such deportations are happening. All Syrians, however, know that they are. Facebook is flooded with posts of the names and photos of deported Syrians, detailing how they were forced to sign voluntary return documents, the degrading treatment they faced during their detention and deportation, including physical abuse and insults.

Syrians in Turkey are reliving their worst nightmares, carried over from their time in Syria where people were detained and even killed by the Syrian regime on a daily basis. In a similar dystopic fashion to how Turkish officials are now denying the deportations, Syrian officials would also use regime media to deny these events. The constant threat of injustice and being subject to rights’ abuses, without any possible legal mechanisms to end it, in addition to the lack of acknowledgement that these violations are existing, is utterly degrading.

Even those who are not in violation of any obligations – meaning those who are living in their provinces with legal permits, a minority – still live under extreme fear. The law does not protect them, and any random Turkish police official could easily strip their rights at any given moment. The high wave of aggression, racist and hateful speech has been a catalyst for exacerbating this fear. Syrians have to deal with this aggression everywhere – from government institutions, on public transportation, in markets and on the streets. Life in Turkey has since become unbearable for the majority of Syrians.

I have now been living in Istanbul for four years, and I have a legal residence permit which is renewed on a yearly basis. However, the start of this new deportation campaign coincided with the period of my old residency expiring and being renewed. I was not committing any legal violation, but I was carrying around an expired residency, so I didn’t dare leave my house or neighborhood for seven days in a row. The stories we heard, of Mohamda Tablyeh for example, who was deported to Syria because he forgot his Temporary Protection ID at home, made me and everyone I know scared of going out to the main streets, to squares or metro stations.

On the eighth day of the campaign, my renewed residency arrived at home by mail. I went out and roamed the streets of Istanbul, intentionally passing places were Syrians usually gather, like Esenyurt square and the Aksaray district. They were noticeably much fewer than usual. Turkish police officers were randomly picking people from the crowd to ask for their documents. I witnessed a few “detention operations”, and every time the “violating” Syrian would be treated with excessive violence. They would be stripped of their phones, handcuffed and dragged to a designated public bus or a police van. One man was fervently trying to explain to an officer – with a flurry of hand gestures, Turkish and Arabic phrases – that his children were alone at home. But the officer did not want to hear it. He dryly replied that his Temporary Protection ID was issued from Gaziantep province, and that he would be deported back to Gaziantep immediately.

I was able to gather enough courage to stop and watch this happen, because I had my residency permit in my pocket, but I didn’t dare intervene and ask the man for his address to, least of all, help out his children. I didn’t dare take a single photo, for I’m still a Syrian and the law does not protect me. I do not know if that man was really returned to Gaziantep or back to northern Syria, but I’m certain that deporting people this way is an unforgivable crime. A father goes to fetch food for his children, and doesn’t come back because he has a document “violation”, and he’s not even allowed to call them on the phone.

A friend called a few days ago, and said he was very sick; high fever, inflamed sores in his throat, and severe abdominal pain but he didn’t dare go to any hospital because his Temporary Protection ID was issued from a different province. I couldn’t find a doctor who was willing to make a home visit, and I was helpless in trying to help him, because I would also not be able to protect him if we went together and were stopped by the police. We finally had the idea of asking a female friend to accompany him to a healthcare clinic, because the Turkish police rarely stop women to ask for their documents, and it would be less likely that they would stop a man accompanied by a woman, although it does happen. The operation was successful in the end, and it was a cause for happiness and celebration. Isn’t it strange that we have now come to celebrate getting access to health care?

These were merely trivial examples of living conditions for many Syrians in Turkey today, and it seems that they are intended to push and force them to return to Syria. However, the war is still raging in Syria: hundreds have lost their lives, thousands have been injured in an extremely destructive military campaign against Idlib, launched by Russia and the Syrian regime in the past few months. Even in places that are not common scenes of daily airstrikes or constant shelling, millions of Syrians are still under numerous deadly threats. Either from attacks and IED explosions by ISIS and other jihadi outfits, or by the Syrian regime’s continuous detention campaign that is still torturing detainees to death, as reported by many human rights organizations, including UN reports. All of these fears are being played out against a backdrop of deteriorating economic conditions, unemployment and absence of food security.

In 2011, hundreds of thousands of Syrians flooded the streets in protests calling for freedom and democracy, in a country ruled by a blood-thirsty autocratic regime for more than half a decade. The regime used quantitatively extreme levels of violence, and committed many massacres that eventually turned the peaceful revolution into a raging war. International and regional interventions have since further complicated the conflict, enshrining chaos and providing the regime the opportunity to crush and annihilate its opposition. Now, after the regime has been able to retake expansive areas with the support of Russia and Iran, countries like Lebanon, as well as the right-wing parties and currents in Europe, have also started taking various measures aimed at pressuring Syrian refugees to go back, regardless of the remaining dangers and threats. Syrian refugees are now being blamed and singled out as the cause of political, economic and social crises in their host countries. This traumatized and hopeless population has already lost so much – their homes, livelihood, friends, loved ones, members of their families and their entire past. In a strange twist of logic, they are now blamed for becoming the root cause of all the troubles in their host countries.

I have no definitive and clear answer to the question of how the world can help end the war, and rid Syrians of the Assad regime, but the world can at least allow Syrian refugees safe spaces to live in. Let us contemplate this reality. The world now has 7 billion inhabitants, but across the whole earth there is no space for 10 million Syrian refugees who are escaping killings and massacres. How is this plausible? It is unbelievable for any sane and reasonable human-being.

Hisham Mustafa is a young Syrian man, who was deported back to Northern Syria in mid July, while his wife and children remained in Istanbul with no support. Hisham lost his life by a bullet fired by Turkish border guards on 5 August, as he attempted to smuggle himself back through the border to be with his wife and children. Many can find an excuse for this incident, saying that he violated the laws and was working without a work permit in Istanbul. One could also argue that the Turkish border guards were merely doing their job in stopping illegal migration, to prevent the smuggling of possible terrorists or armed individuals. Nevertheless, all these excuses do not change the reality that Hisham was a young Syrian man searching for a better life, that his life and that of his family were ruined, that he was killed because the laws of the world we now live in are not inclusive enough for him, his family or others like them.

Sadek Abdul Rahman is a Syrian journalist and Editor at Aljumhuriya.